The Civil War’s Monster Batteries: The XX-Inch Rodman and Dahlgren Guns

A host of different artillery types were used in the United States Civil War. Guns large and small, smoothbore and rifled, were cast and pressed into service in both the armies and navies of both sides. These guns were organized into batteries, placed into fortifications, or mounted onto ships.

While smaller artillery pieces were most common in field armies, there were experiments at forging massive guns for fortifications and ships, with many ironclads mounting guns as large as XV-inch Dahlgrens. Somehow, even those XV-inch guns were not the largest on record. During and immediately after the war, the United States experimented with forging and testing behemoth XX-inch smoothbore Rodman and Dahlgren guns for use in fortifications and aboard ship.

To bring the size of these guns into a true measure of scale requires some modern comparisons. Modern-day U.S. field artillery batteries utilize 105-millimeter or 155-millimeter howitzers, which equate to approximately 4-inch and 6-inch guns. Navy destroyers and cruisers today use 5-inch guns for direct kinetic firing. The closest we can get from relatively modern artillery would be decommissioned battleships. The now retired Iowa-class battleships used 16-inch guns, but somehow in the Civil War they were creating artillery with a larger bore diameter!

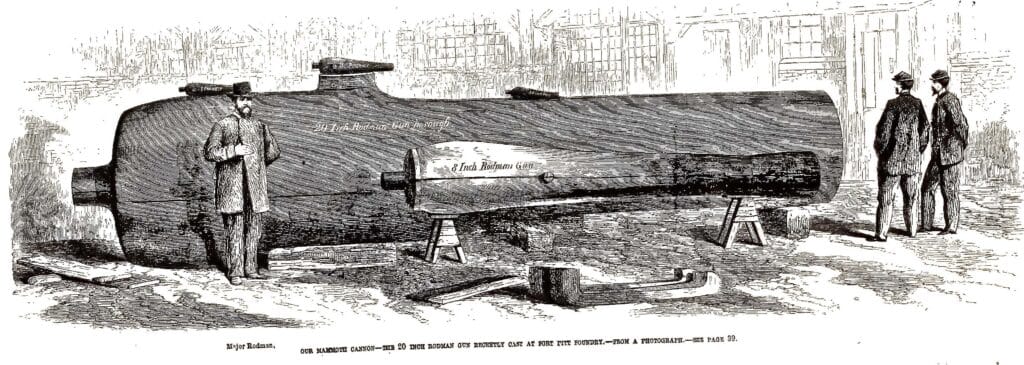

“The Monster Rodman Gun,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 9, 1864

At least six XX-inch guns were forged by the United States during and immediately after the Civil War. All were created at the Fort Pitt foundry in Pittsburgh. Two of these were created by the famed artillery designer Thomas J. Rodman for use by the army. Even as they were created, their size was noted by the public. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper ran both an article and image of one of the Rodman guns in their April 9, 1864 issue. Leslie called it “a monster cannon of the Rodman pattern,” noting its final weight as 112,000 pounds and its overall length as 20 feet 3 inches.[1] Leslie also claimed the gun could fire shells weighing 750 pounds.

At least two XX-inch Rodman guns were forged. One was sent to Fort Hamilton, protecting Brooklyn. There it was “fired only a few times since no target could be found sufficiently tough to resist the impact of 1,080 pound solid-shot propelled by 100-pound service charges.”[2] A second was made in 1869, and was displayed in Philadelphia before being moved to Sandy Hook, New Jersey in the 1870s. It remains at Fort Hancock, Sandy Hook, New Jersey, never having fired a shot in anger.

The navy was also interested in XX-inch guns, and John A. Dahlgren began thinking about the possibilities of them in 1862. In January 1864, Captain Henry Augustus Wise, chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, testified to the U.S. Senate that the Navy Department “was about to cast a 20-inch gun – to be cast on Rodman’s method of the Navy form.”[3] An 1864 report copied in Dahlgren’s memoir admits that at least one XX-inch gun was manufactured that year, and that when tested “the XXin. gun has broken up and shattered plates [iron plating] exceeding in thickness anything hitherto proposed as defensive armor.”[4]

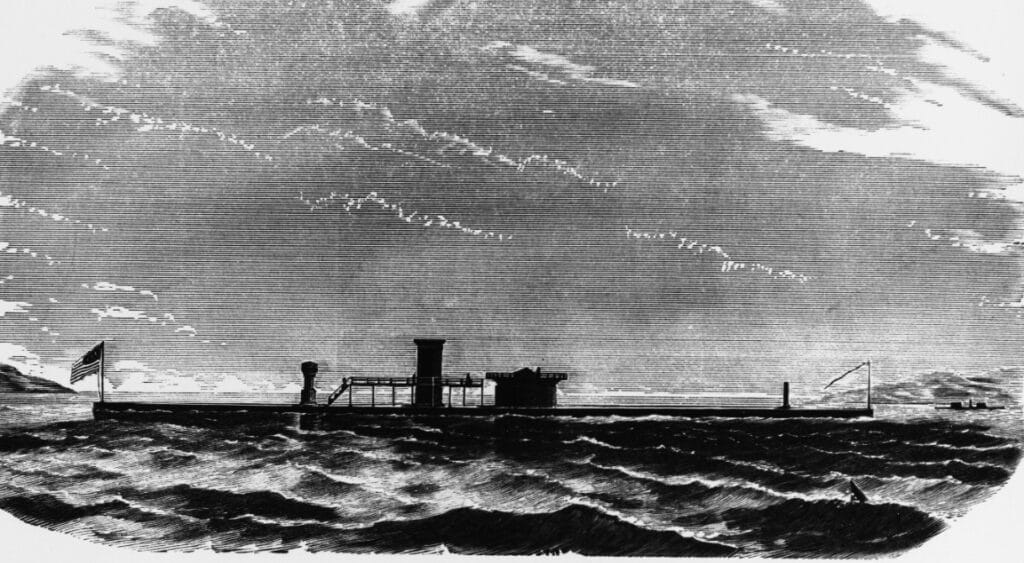

Four XX-inch Dahlgrens were ultimately ordered, intended for mounting on the ironclad Puritan. This was envisioned as an ocean-going Monitor, originally planned for two turrets, each housing a pair of the behemoths. To maintain seaworthiness and buoyancy, one of the turrets was eliminated from the plans in 1865. When the Civil War ended, Puritan remained unfinished; it was ultimately scrapped in 1874.

Even though Puritan was never finished, the four XX-inch Dahlgren guns were completed by 1867. They quickly developed nicknames tied to Hell itself: Satan, Lucifer, Moloch, and Beelzebub. The names stand in stark contrast to Confederate artillerist William Nelson Pendleton’s battery, where the guns were purportedly named Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John in honor of the four Gospels of the Bible. One of the Dahlgrens – Beelzebub – was ultimately sold to Peru, where it joined in the fortified defenses of Callao.[5] The other three were accepted by the Navy Department, but sat idle and unused. None are known to still exist.

The weight, size, and massiveness of these XX-inch guns represent many things. They demonstrate how the Civil War brought forth continued experimentation in artillery design. As ironclads became the dominant warship, everyone sought ways to pierce armor. Heavier and larger guns was one such solution. These guns also represent the might of the industrial capacity of the United States. They may never have seen combat in the Civil War, but these XX-inch Rodman and Dahlgren guns represent just how much the United States was willing to invest in preserving the Union.

Endnotes:

[1] “The Monster Todman Gun,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 9, 1864.

[2] Warren Ripley, Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War (New York: Promontory Press, 1970), 80.

[3] Ripley, Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War, 100.

[4] Madeline Vinton Dahlgren, Memoir of John A. Dahlgren (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1882), 303.

[5] One source claims that one XX-inch Dahlgren and one XX-inch Rodman gun, possibly a third one created at Fort Pitt foundry, were at Callao. See Jack Greene and Allesandro Massignani, Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854-1891 (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1998, 324.

Were any of these guns ever used in action?

Hey Mike. So at least one of the Rodmans were test fired, but they were never used in combat. The only of the Dahlgrens that may have been used in combat was the one sold to Peru. So far I have not seen any definitive proof either way on that though.

These pieces certainly would put the “thunder” into Battle’s Thunderous Roar. Fascinating dive into their history!