“The ground was black with their dead”: Du Bois’ Battery at Wilson’s Creek

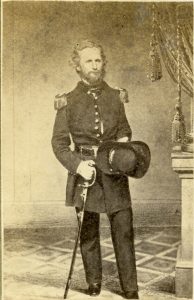

First Lieutenant John Van Deusen Du Bois was irritated. “Finally I received orders to return to New Mexico,” he wrote with undisguised disappointment, “so much for giving up a leave of absence to serve my country.”[1] With the fate of the country at risk, the young officer had wired the War Department from Detroit nearly two months prior to end his leave and return to duty. His offer was accepted.[2]

From Du Bois’ perspective, the War Department was returning him to a southwestern backwater. Rather than preparing the new volunteers, he had the inauspicious duty of conducting new Regular Army recruits to their Western posts. What appeared to be a wandering journey away from glory and advancement instead led Du Bois to command of a battery in a defining struggle of the war’s first summer: the battle of Wilson’s Creek.

A high-ranking graduate of the West Point Class of 1855 from New York, Du Bois’ prewar military service with the Regiment of Mounted Rifles was defined by simmering conflicts with the Apache, Navajo and Comanche in the Southwest.[3] His private letters reveal an eagerness to confront the secessionist foe. Writing to his father, he assessed that, “war was inevitable, and the sooner it comes, the sooner it will be over.” [4]

Du Bois and several fellow officers departed with 255 recruits from Carlisle Barracks on June 2, 1861. They arrived at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas five days later, despite a delay caused by rumors of a secessionist mob in St. Joseph, Missouri.[5]

Events soon altered their planned course dramatically. Missouri was riven by internal strife and threats of secession. Less than a month earlier, a zealous Federal commander, Nathaniel Lyon, had dispersed a pro-secessionist militia camp near St. Louis, sparking a riot that led to the death of 28 civilians. A rapid escalation between Unionist elements aligned with Lyon and Missouri congressman Frank Blair against pro-secession forces allied to Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson progressed to open conflict by mid-June. Lyon captured the state capital at Jefferson City by mid-month and sent the state executive fleeing to the southwestern corner of Missouri.

The War Department thus determined a different role for Lt. Du Bois and his compatriots. On June 10, 1861, “just as we were striking our tents to march to Fort Union” in New Mexico, they received a telegram “to remain where we were at present.”[6] Lyon needed all the experienced soldiers available. Federal control of Missouri was threatened by the mobilization of the pro-secessionist Missouri State Guard and Confederate troops were poised to enter the state.

Du Bois was also assigned a different responsibility: command of a newly organized battery of field artillery. The battery that carried his name during its short existence was a scratch outfit, “six guns, horses unshod, no forge, and everything rather incomplete.”[7] Du Bois set to the task of preparing it for field service, and by June 31, 1861 it set out from Kansas as part of the column under Maj. Samuel Sturgis to join Lyon in the field. Among its complement was a 12-pounder M1841 field gun – not howitzer – the heaviest field artillery piece in the theater at the time and capable of firing at targets a mile distant.

Du Bois’ initial service in Missouri was frustrating. “Is there any way to get me and all the Regulars here to the East?” he queried his father in late July. “We are of no account here, perfectly useless,” DuBois deduced, adding, “we have nothing to gain here except play constable for a state without a governor or treasury.”[8] He was also relentlessly critical of the German American element of the Missouri Unionist forces: “Damn the Dutch element of Missouri. They are useful but cowardly,” adding in later, “one feels as if we were sold to the Dutch in this army.”[9]

As Lyon’s force advanced deeper onto the Ozark plateau towards the Arkansas border, their road-bound supply line stretched ever longer. There was also growing concern. The Missouri State Guard organizing at Cowskin Prairie significantly outnumbered the small Federal force – and more Confederate and state troops from Arkansas were on their way.

It was an isolating vigil with daunting consequences. “General Lyon is our hope now,” Du Bois informed his sister. “If it is retrievable one week from today Missouri will be free from secession,” he predicted, while cautioning, “If he fails Missouri will be out of the Union.” As the two armies shadowboxed, the moment of crisis was close at hand. “A few days will tell the tale,” Du Bois advised, “Success will make us, defeat will ruin us. On the two horns of the dilemma we wait the fortune of war.” Perhaps shaken from his earlier malaise by martial opportunity, Du Bois added: “Missouri must be saved.” [10]

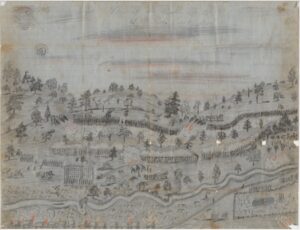

Saturday, August 10, 1861 was stiflingly hot, with temperatures in excess of 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The previous evening, Lyon’s 5,500 men departed Springfield on a 12-mile night march to ambush the rebel camps scattered in the bottomland and fields astride Wilson’s Creek. The plan was both audacious and foolhardy. Lyon would divide his inferior force, sending a portion under Col. Franz Sigel to surprise the unexpecting and ill-trained rebels, crushing them between the two wings of his army.

Fighting began shortly after 5 o’clock in the morning, with the Federals achieving a near-complete surprise. Lyon arrayed most of his force along a gentle spur known locally as Oak Hill, thereafter forever referred to as Bloody Hill. DuBois, commanding his now four-gun battery, took up a position on the far right of the line, about 400 yards away from the opposing Confederate batteries, and commenced counterbattery fire.[11]

Du Bois witnessed the repulse of the Federal left flank in the Ray cornfield opposite the creek, “driven back by an overwhelming force of the enemy.”[12] He responded decisively, and “by a change of front to the left I enfiladed their line and drove them back with great slaughter.”[13] While a gratuitous overstatement – Maj. William Tunnard of the 3rd Louisiana Regiment reported only a handful of casualties from this artillery barrage – it demonstrates the terrifying psychological effect of artillery on inexperienced soldiers at Wilson’s Creek.[14]

Du Bois used his ordnance advantage to good effect. His battery, particularly the 12-pounder field gun, significantly outranged those of his rebel opponents. They struck the distant Ray farmhouse twice with long-range fire until a yellow hospital flag was displayed.[15] His battery also suppressed rebel artillery attempting to disrupt the Union defense, noting that “our guns commanded their camp and kept down completely their artillery.”[16]

Nevertheless, the pressure of rebel numbers came frighteningly close to the muzzles of Du Bois’ guns. “The underbrush was so thick that a line of troops came up within twenty yards of my guns before I saw them, and nearly carried my guns,” Du Bois recounted, with the observation that the repulse was, “very bloody.”[17] A larger second assault, which Du Bois described as “very desperate”, saw the enemy come within forty yards before beginning to fire.[18]

As the rebels began another assault on Bloody Hill, the Federal army was ordered to retreat. Lyon was dead, struck down after multiple wounds. Sigel’s force, after a stunning initial success, was was routed with fearful loss by a surprise by a secessionist counterattack. The Federals on Bloody Hill had suffered severe losses, and their ammunition was badly depleted. Du Bois was ordered by Lyon’s successor, Samuel Sturgis, to serve as part of the rearguard for the army as it retreated to Springfield.[19]

Despite high praise from his new commander, Du Bois shared the sentiment of many of the Federal veterans of Wilson’s Creek, “I was never so astonished in my life,” recounting that his men could not “be convinced that we were not victorious.”[20] He was further disappointed after receiving the escort for Lyon’s body sent by General Sterling Price of the Missouri State Guard, who offered that the rebel forces were near to breaking when the Federal retreat was ordered. “O Sturgis, Sturgis, how weak you have been!” he bemoaned, “So great a chance for glory, coaxed by the best of your officers to attack too, and all thrown away.”[21]

Wilson’s Creek was a savage introduction to the reality of war. Du Bois described the battlefield as “so covered by their dead and wounded that it was necessary to carry them together to get room to work our guns. The trees had been stripped of all their lower branches by the shot of the enemy, and everything was covered in blood.”[22]

In contrast to many of the infantry regiments on Bloody Hill, Du Bois’ battery was seemingly unscathed, reporting only two wounded and one missing from the 66 men who were in the battle.[23] These reports, especially in the early days of the war, did not measure the full toll taken from the ferocious volume of fire. Half of his guns were disabled; the physical toll was worse.[24] “Many of the company, myself included, were struck and slightly injured by spent musket and canister shot,” noted Du Bois, without these casualties appearing in formal reports. Months later, Du Bois continued to experience significant pain from a spent canister round that struck him during the fighting.[25]

Du Bois was among the most ardent critics Col. Sigel’s, who had successfully persuaded Lyon of the unsuccessful two-pronged attack. He co-signed a scathing statement of facts and critique of Sigel that was submitted to the department commander, Henry W. Halleck.[26] His private attitude was unambiguous as to Sigel’s culpability: “All the guns lost were Sigel’s. All the defeat was Sigel’s. All the men killed were Lyon’s.”[27]

Du Bois ambition was heightened in the aftermath of Wilson’s Creek, with his name among the leading lights feted in St. Louis and in cities across the North.[28] Unwilling at first to be separated from the battery he led at Wilson’s Creek, he rose to brigade command under Grant and Rosecrans in 1862 and served with distinction at Iuka and Corinth.[29] While he would fulfill various senior staff roles for the duration of the war, and another ten years in the postwar Regular Army, he would never exceed the public recognition he received for being among Lyon’s gallant few on the slopes of Bloody Hill.

Endnotes:

[1] John Van Deusen Du Bois. “The Civil War Journal and Letters of Colonel John Van Deusen Du Bois, April 12, 1861 to October 16, 1862.” Jared Lobdell, ed. Missouri Historical Review (MHR) 60: 444.

[2] Ibid, 437.

[3] George W. Cullum. Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U. S. Military academy at West Point, N. Y. (New York: J. Miller, 1879), 399.

[4] Du Bois. MHR 60: 441.

[5] Ibid, 446.

[6] Ibid, 446.

[7] Ibid, 447.

[8] Ibid, 458-459.

[9] Ibid, 454; 456.

[10] Ibid, 452.

[11] The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 3, 80.

[12] Ibid, 80.

[13] John Van Deusen Du Bois. “The Civil War Journal and Letters of Colonel John Van Deusen Du Bois, April 12, 1861 to October 16, 1862.” Jared Lobdell, ed. Missouri Historical Review (MHR) 61: 30.

[14] OR, Series 1, Vol. 3, 117.

[15] OR, Series 1, Vol. 3, 80.

[16] Du Bois. MHR 61: 30.

[17] Ibid, 30.

[18] Ibid, 31.

[19] OR, Series 1, Vol. 3, 80.

[20] Du Bois. MHR 61: 31; OR, Series 1, Vol. 3, 80.

[21] Du Bois. MHR 61: 36.

[22] Du Bois. MHR 61: 31.

[23] OR, Series 1, Vol. 3, 72.

[24] Du Bois. MHR 61: 31.

[25] Du Bois. MHR 61: 39.

[26] OR, Series 1, Vol. 3, 95-98.

[27] Du Bois. MHR 61: 35.

[28] St. Louis Globe-Democrat (September 13, 1861), 2.

[29] OR, Series 1 Vol. 17, Part 1, 68, 75.

Interesting article. Thank you.

Appreciated your research and the interesting story about a battery I knew nothing about.

Enjoyed the story. Thanks

Dale Klassen

I call the Grand state of Missouri home. We have a Ranch 30 minutes south east of the Battle field. The area has camp features North and south . Ie was actually a pretty good fight some of my family rallied to both sides and the south was green a grass . The battle was hot and deadly for the early days . The high light of the battle was the battery that was well placed. The shortage of any kind of fire arm the south shows it was old Pappy Price new that they about broke broke them the . My grate grate grandpa went around the union line at Springfield. He was mad as a wet hornet ! Cause he had nothing. He went on to find a rile and went to the sound or guns . He came home with it as proof of his part and recalled he thought he would have to change sides to get home .

Is