Thanksgiving Under Siege: A Holiday in Knoxville

In the fall of 1863, fresh off their victory at Chickamauga, the Confederate Army of Tennessee’s long-simmering resentments finally boiled over. Frustrated by the half-hearted pursuit of the defeated Union Army of the Cumberland, years of missed opportunities, and their commander’s abrasive personality, Braxton Bragg’s subordinates verged on open revolt. Jefferson Davis traveled from Richmond to Bragg’s army headquarters, where he tried and failed to hash out their differences.

Bragg was ultimately retained in command, and ready to be done with some of the ringleaders of the failed attempt to oust him, he quickly dispatched James Longstreet to eastern Tennessee. Along with his battle-hardened First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, Longstreet’s mission was to confront Union Major General Ambrose Burnside’s offensive until the heavily Unionist region.

In spite of the Lincoln administration’s insistence that it be a priority, the vast logistical challenges facing any move by a sizable force into the area had long caused Union commanders to balk at an eastern Tennessee campaign. The remote, mountainous region offered very limited foraging for a large army. More organized supply lines had to stretch back north to the Ohio River along hundreds of miles of poorly developed roads that were vulnerable to cavalry raids and guerrillas.

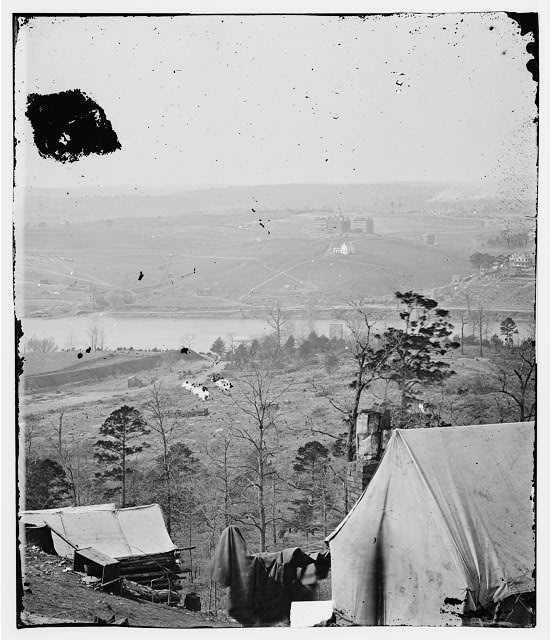

Despite the challenges, Burnside took advantage of weak Confederate defenses to push through the Cumberland Gap and into Knoxville. Upon hearing that Longstreet was approaching, he fought a series of delaying actions to buy time to consolidate the city’s defenses. While he was gradually forced back, he kept his force largely intact, and was able to successfully withdraw behind strong earthworks that Longstreet wouldn’t be able to breach easily.

In October, President Lincoln had issued one of his nine proclamations declaring a day of Thanksgiving, this one to be celebrated on the final Thursday of November.[1] As the day arrived, Burnside was still hunkered down inside of Knoxville, and issued the following orders to observe the day:

“In accordance with the proclamation of the President of the United States, Thursday, the 26th instant will, so far as military operations will permit, be observed by this army as a day of thanksgiving for the countless blessings vouchsafed the country and the fruitful successes granted to our arms during the past year.

Especially has this army cause for thankfulness for the divine protection which has so signally shielded us; and let us with grateful hearts offer our prayers for its continuance, assured of the purity of our cause and with a firm reliance on the God of Battles.”[2]

The besieged rank and file of Burnside’s Army of the Ohio must have read these orders with some sense of irony. The muddy trenches and limited rations would have put a real damper on their appreciation for their “countless blessings.” While experienced varied by unit — and undoubtedly by rank — one regiment reportedly celebrated by giving each man a single raw onion.[3]

Ultimately, however, the siege was only partial; Longstreet lacked the manpower and knowledge of the local geography to fully invest the city. Shortly after their Thanksgiving celebration, Burnside’s army decisively repelled a Confederate attempt to storm the critical bastion of Fort Sanders. A few days later, Longstreet withdrew into the mountains in the face of a Union relief force, and Sherman arrived to find Burnside comfortably eating dinner.

As you celebrate Thanksgiving this year, be grateful that you aren’t doing it under siege, even a partial one. And if you’re looking to read more about this underappreciated Civil War campaign, check out A Fine Opportunity Lost: Longstreet’s East Tennessee Campaign, November 1863 – April 1864, part of the Emerging Civil War Series, by Ed Lowe (Col., Ret.).

[1] Lincoln and Thanksgiving. National Park Service. November 27, 2024.

[2] United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume XXXI, Chapter X:III. 1880, 248.

[3] Lowe, Ed. A Fine Opportunity Lost: Longstreet’s East Tennessee Campaign, November 1863 – April 1864. Savas Beatie, 2023. 121.

Nice post, Pat. Happy Thanksgiving to you and hope you celebrate NOT under siege.