An Antietam Death in 1881: The Tragedy of a Lingering Mortal Wounding

ECW welcomes back guest author Danny Brennan.

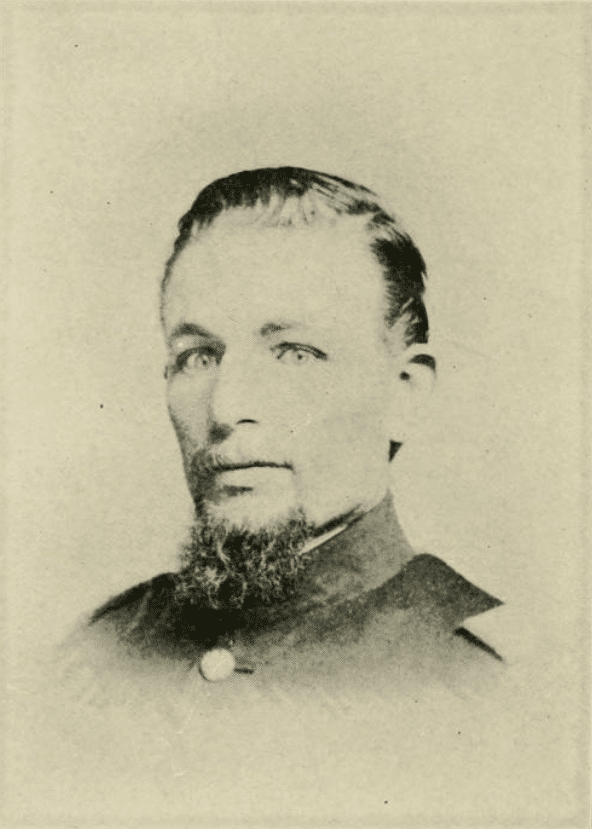

Ernst Krieger couldn’t take it anymore. By 1878, the 45-year-old had suffered a stroke of paralysis for the fourth time in as many years.[1] As his health deteriorated, he decided it was time to move into the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Dayton, Ohio for some relief.[2] A veteran of the Civil War, he survived his country’s greatest conflict. Still, he carried a wound that lingered with him and brought about his 1881 death, all from America’s bloodiest day.

September 17, 1862 dawned for the 7th Ohio Infantry not with the bugle, but with, according to one soldier, “a fierce volley of musketry.”[3] Company K commander Lt. Ernst Krieger took the time to check on his men. Most were German immigrants and members of the Cleveland Turnverein, a club that promoted athletics, culture, and progressive politics. When the first Southern states seceded in the winter of 1860-61, the “Turners” formed the Cleveland Volunteer Rifle Company to protect “the stability and perpetuity of our adopted fatherland.”[4]

Krieger, a native of Bingen am Rhein who migrated to the United States in the 1850s, helped organize the Rifle Company and wrote its mission statement. He and his fellow Turners mustered into service in the spring of 1861 and followed the 7th Ohio through its early battles at Kessler’s Cross Lanes, Kernstown, Port Republic, and Cedar Mountain.

A year’s worth of fighting had dramatically thinned the 7th’s ranks. The unit numbered only 156 men at Antietam.[5] Similar losses in the 5th and 66th Ohio led to an operational consolidation of the units into a force of 425 officers and men. Each command still retained its flags and officers due to unit pride, as demonstrated by one member of the 7th who called total consolidation “unjust and ungenerous.”[6] The awkward arrangement found a place with the large 28th Pennsylvania in Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale’s brigade of Brig. Gen. George S. Greene’s 2nd Division of the XII Corps

After preparing supplies and boiling coffee, Greene’s division was ordered to march towards the firing that had woken them. Wounded men of the I Corps and their own corps’s 1st Division streamed around them. The Ohioans formed in the East Woods, where their corps commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Mansfield, had just been mortally wounded. As artillery and rifle fire thundered nearby, the regiment steadied itself for a fight.

The Ohioans stood at the right of the division and “poured an incessant fire” into enemy ranks until ordered forward.[7] “Away we went shouting like madmen,” remembered Pvt. Charles Tenney, noting how the Confederates retreated “at full speed closely followed by our brave boys.”[8] Greene’s blue line pushed on over fences, bodies, and the Smoketown Road until the enemy established itself in the West Woods.

The Union juggernaut paused on the reverse slope of a high plateau east of the Dunker Church, ground that Confederate artillerists had used throughout the morning. Federal cannon quickly unlimbered on the natural platform. The 7th Ohio stood in the rear of the guns, which quickly became targets. One soldier said that the low ridge was “sufficiently high to protect us from a direct shot,” but nevertheless “offered no shelter from the fragments of shells bursting near and over us.”[9]

Above the cacophony of shot and shell, the 7th’s men heard yells from the direction of the West Woods. To their right, they saw retreating comrades from John Sedgwick’s division of the II Corps. The Ohioans, recently replenished with ammunition, marched up the rise in their front and prepared for an enemy attack. An aggressive force of South Carolinians advanced from the woods and met Buckeye fire at a range of 50 yards. Major Orrin Crane, commanding the regiment and later the brigade, said that the fire caused the enemy to fall “like grass before the mower.”[10] Another attack further to the left of Greene’s line featured more men and even some artillery. But that, too, ended in a Confederate failure.

By this point, Lt. Krieger was likely already wounded from a shell piece in his head,[11] perhaps hit when the regiment formed in the East Woods, when they supported a friendly battery near the Dunker Church, or during the second Confederate attack from the West Woods, all times when the regiment dodged cannon fire. Krieger was one of a full quarter of his unit who were casualties of Antietam.

Krieger recovered quickly enough to fight with the 7th during all of its remaining engagements. Promoted to captain, he briefly commanded the regiment after the November 1863 battle of Ringgold Gap where every regimental officer was either killed or wounded. When discussing that battle, the regimental historian ironically called him “one of the most fortunate officers, so far as casualties went.”[12] He was fortunate enough to muster out with his regiment in July 1864 and later rose to the rank of major in the 177th Ohio. His luck, however, faded in his postbellum life.

When he returned to Cleveland in 1865, Krieger resumed life alongside old comrades. The Society of Survivors of the Seventh Regiment O.V.I. elected him vice president in 1866, a reflection of his leadership and popularity.[13] He rejoined the Turnverein and remained an active voice in the German-American community. In 1874, he was chosen as grand marshal of a large cultural parade.[14]

When he wasn’t participating in social groups, Krieger worked as a machinist, building enough success to co-own the firm “Gaeckley & Krieger” by 1872.[15] The lingering financial shadow of the Panic of 1873 crippled the business and the firm closed within a few years. He subsequently took a modest job as a doorman at the Cleveland Central Police Station.[16] The proud officer who had once led men in battle was now opening doors for others.

Krieger’s personal issues dwarfed his career problems, in large part because of his unsavory actions. Not long after his Antietam injury, his wife, Mary, filed for divorce, citing “gross neglect of duty” and “willful absence for three years.”[17] They had been married only three years. The divorce was granted, but his bad behavior did not end there. In 1869, he was tried for “having seduced one Elizabeth Metz.”[18] The case’s outcome is unknown, but its public nature undoubtedly hurt his reputation.

As the veteran navigated social leadership, business troubles, and legal complications, the effects of his Antietam wound increasingly caught up with him. It first flared as a stroke of paralysis in 1875. The attacks became annual, each leaving him weaker. By 1878, after his fourth stroke, he could barely function. He left his job and entered medical care in Dayton. A subsequent operation in Cleveland failed to help. Soon, he lost his ability to speak.

When he returned to the Soldiers’ Home in Dayton, he was entirely helpless. “He lay on his bed, unable to move hand or foot, and had to be fed and nourished by attendants,” one report noted.[19] Ernst Krieger died in this condition on March 14, 1881.

For those who fought in the Civil War, survival did not always mean prosperity. The smoke cleared, the armies moved on, but the war lived on in their bodies. Krieger was one of those people, and his life was filled with complications and contradictions. He was an immigrant who succeeded in serving his adopted country, only to fail in postbellum business. He was a respected officer and social leader who tarnished his reputation due to personal indecency. He was an active man who died while unable to move. His story is the story of a lingering war—the one fought long after the guns went silent.

Danny Brennan is a PhD candidate at West Virginia University who works as a seasonal ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park. He is interested in exploring the culture and experience of Union soldiers in war and memory.

Endnotes:

[1] Cleveland Leader, March 18, 1881.

[2] Cleveland Leader, October 25, 1878.

[3] “From the Seventh Regiment,” Western Reserve Chronicle, October 22, 1862.

[4] Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 9, 1861.

[5] R. S. Bower, “From the Seventh Regiment,” The Jeffersonian Democrat, October 3, 1862.

[6] “From the Army of the Potomac,” Cleveland Tri-Weekly Leader, November 11, 1862.

[7] Charles Tenney to Adelaide Case, September 21, 1862, Charles Tenney Civil War Letters, 1861-1863, Accession #11616, Albert H. Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va (UVA).

[8] Charles Tenney to Adelaide Case, September 21, 1862, UVA.

[9] “From the Seventh Regiment,” Western Reserve Chronicle, October 22, 1862.

[10] OR, ser. I, vol. 19, pt. 1, 506.

[11] “A Veteran’s Funeral,” Cleveland Leader, March 18, 1881.

[12] Lawrence Wilson, Itinerary of the Seventh Ohio Volunteer Infantry (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1907), 290.

[13] Cleveland Leader, September 11, 1866.

[14] “The Saengerfest,” Evening Post, May 27, 1874.

[15] W.S. Robison & Co.’s Cleveland Directory, 1872-73 (Cleveland: W.S. Robison & Co., 1872), 281.

[16] Evening Post, August 12, 1878.

[17] Evening Post, October 16, 1862.

[18] “Bound Over for Trial,” Cleveland Leader, February 9, 1869.

[19] “A Veteran’s Funeral,” Cleveland Leader, March 18, 1881.

Dear Danny Brennan, You mention an action at “Smoketown Road” during the battle of Antietam, and I am trying to figure out where that road actually was. I assume it was renamed in later years, as Smoketown, MD, no longer officially exists. Do you have any info or advice? My daughter and her family live on a farm in what was Smoketown, and since I’m a “Civil War guy” and author, I’m trying to research the history there. Thanks!

Thank you for your excellent question! The most significant part of the road to this story is south of the Cornfield and east of the West Woods, along an area of ground still labeled the “Smoketown Road.” However, the whole path is a decent bit longer.

As you point out, the small settlement of Smoketown no longer exists. That said, large traces of the road still exist, its northern point beginning along the Keedysville Road, where the historic Smoketown once stood. The modern road (still called the Smoketown Road) fits the course of the historic road, traveling variably southwest and south for about a mile and a half until it meets up with the modern Mansfield Avenue. The historic road then ran into what is now a recently replanted section of the East Woods, just slightly to the west of the modern stretch of road. There is a trail in the woods that conforms to most of the old road, taking you to and eventually south of the modern Cornfield Avenue. The historic road picks up where the trail meets the modern Smoketown Road to the south, and from there conforms to the current road in its diagonal Southwest course. This diagonal line eventually links with the Hagerstown Pike just in front of the Dunker Church.

The 7th Ohio followed the road north of modern Mansfield Avenue to get to the front. They went off the road to enter the East Woods and begin their engagement. Following this, they proceeded about half a mile through the famous Miller Cornfield and neighboring grass field to the south before joining up with that final diagonal stretch of the road.

I hope this is helpful! I recommend reading this with a modern and historical map handy. The best map that reflects 1862 conditions is the base map put out by the Antietam Institute. It is detailed and extensive, even including the historic Smoketown settlement in the northeast.