Skirmish at Cloud’s Mill: Unraveling an Early Civil War Mystery

ECW welcomes back guest author M.A. Kleen.

Shortly before midnight on May 31, 1861, two companies of raw recruits, barely trained to hold their muskets in formation, attempted a routine shift change under the cover of moonlight at an outpost several miles from camp. They had been in enemy territory for just a week and likely imagined bushwhackers hiding behind every tree. Suddenly, shots rang out. In the chaos that followed, one man was wounded and another killed.

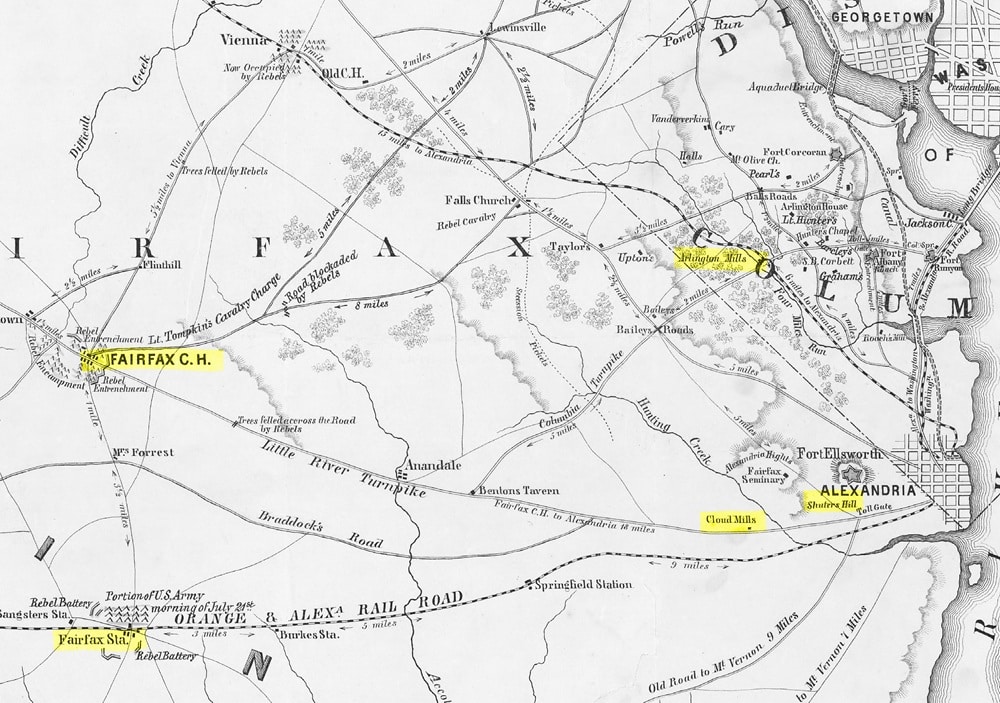

This confrontation at Cloud’s Mill, just a few miles west of Alexandria, Virginia, has long been considered one of the first skirmishes of the Civil War. But was it? Over the decades, the date and location of the incident have been obscured, and what was once assumed to be enemy fire may not have been hostile at all. Uncovering the truth behind this early Civil War mystery is anything but straightforward.

At 2 a.m. on May 24, 1861, Union volunteers crossed the bridges from Washington, D.C., into northern Virginia and by boat to Alexandria. The 1st Michigan Volunteer Infantry (three months), led by Col. Orlando B. Willcox, crossed Long Bridge and advanced overland to Alexandria, while the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry (First New York Zouaves), led by Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, arrived by boat via the Potomac River.

Ellsworth, a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln, was killed by the proprietor of the Marshall House inn shortly after removing a Confederate flag from its roof. Virginia militia forces fled the town, destroying bridges and sections of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad as they retreated. By May 28, both the 1st Michigan and the 11th New York had set up camp on Shuter’s (or Shooter’s) Hill, west of Alexandria along the Little River Turnpike (now Duke Street) leading to Fairfax Court House.[1]

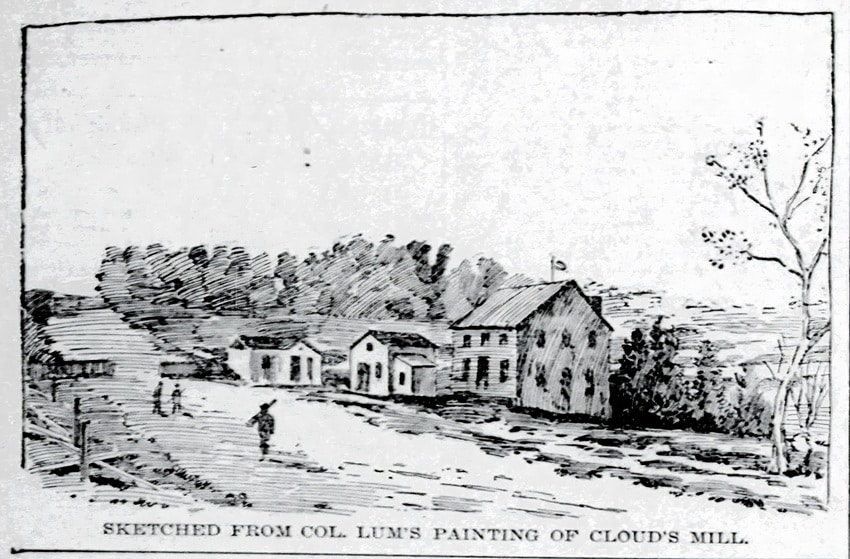

About three miles west of Shuter’s Hill, near Holmes Run on the north side of the turnpike, stood a mill owned by James Cloud. The four-story brick structure was “noted for nothing but the millions of horrible fleas bred in its vicinity.” Its wheel was powered by a muddy stream, largely hidden by weeds and brush. Captain Ebenezer Butterworth and Co. C of the 1st Michigan—the “Coldwater Cadets”—seized the mill, confiscating 400 barrels of flour and hundreds of bushels of wheat. Southern newspapers accused them of evicting the Cloud family and ransacking their home.[2]

Built between 1813 and 1816, the mill was previously called Triadelphia Mill under owner Mordecai Miller. James Cloud owned it from 1835 to 1863, and it came to be known as Cloud’s Mill.[3]

Around the same time, Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee visited Manassas Junction to inspect Brig. Gen. Milledge L. Bonham’s defensive preparations. Lieutenant Colonel Richard S. Ewell, a former U.S. Army officer, assumed command of the Virginia cavalry at Fairfax Court House, where the Warrenton Rifles, Rappahannock Cavalry, and Prince William Cavalry were stationed. These units were poorly armed, and the Warrenton Rifles had just arrived. The Goochland and Hanover Light Dragoons were positioned at Fairfax Station, 3.5 miles south.[4]

On the night of May 31, about 25 men from Co. E, the “Steuben Guard” of the 1st Michigan, were stationed on picket duty at Cloud’s Mill under Captain William F. Roth. Company G of the 11th New York, led by Capt. Michael A. Tagan, was preparing to relieve them. Around 10 p.m., impatient Michigan soldiers began walking back to camp to check on their replacements. The two groups met on the road and returned to the mill together.

Accounts differ on what happened next. It’s generally agreed that some members of the 1st Michigan were inside the mill, while the New York Zouaves took position in a nearby storehouse. In the darkness, a sergeant spotted figures emerging from a barn. “Who goes there?” he demanded twice. Unsatisfied with the reply, he raised his musket and fired. A volley followed. The Michigan troops, firing from inside the mill, couldn’t tell friend from foe in the confusion.

Captain Roth ran outside to assess the situation, but dropped to the ground to avoid the crossfire. Two soldiers from the 11th New York, 21-year-old Pvt. Henry S. Cornell and Pvt. Joseph Cushman, were hit, Cornell mortally. As he lay dying, Cornell reportedly said, “Who would not die a soldier’s death?” After the gunfire stopped, troops searched the woods, but found no sign of enemy soldiers.[5]

Northern journalists, unfamiliar with the local geography, initially misreported the site as Arlington Mills, three miles to the north. That well-known grist mill on Four Mile Run in Arlington County, once owned by George Washington Parke Custis (Robert E. Lee’s father-in-law), was a prominent landmark along the Columbia Turnpike. The name “Skirmish at Arlington Mills” stuck.

Most believed the pickets had been ambushed by enemy forces, but others were not convinced. In a July 3, 1861, letter published in the New York Leader under the pseudonym Harry Lorrequer, Pvt. Arthur O’Neil Alcock, a former newspaper editor in Co. A of the 11th New York, wrote: “The simple fact is, that since we left New York we have had only one man killed and two wounded, as is said, by the fire of the rebels. And it is by no means certain that these were not shot by friends in mistake, or by themselves accidentally or through carelessness.”[6]

A New York newspaper excerpt reprinted in the Philadelphia Inquirer added: “The remains of private Cornell, of the New York Zouaves, who was shot accidentally by one of the picket guards, the other day, were conveyed to Greenwood Cemetery, this afternoon.”[7]

If Cornell and Cushman were shot by the enemy, who was responsible? The list is short—only a few Confederate companies were in the area. In his account of the skirmish at Fairfax Court House, William “Extra Billy” Smith made no mention of any Confederate movement toward Union lines the night before. When U.S. cavalry arrived at Fairfax Court House on the morning of June 1, they encountered only a few Confederate pickets. Some were captured, others fled. The rest were reportedly asleep when the alarm was raised.[8]

The simplest and most likely explanation is that, in the dark and confusion, with raw recruits jumpy and unfamiliar with the terrain, Union pickets mistakenly fired on one another. But without more evidence, the truth may never be known.

Cornell was given a hero’s funeral, attended by his entire company. He was first buried beneath a tree near Camp Ellsworth, then later exhumed and reinterred at Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.[9]

Although The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. II, list the “Skirmish at Arlington Mills” as taking place on June 1, 1861, contemporary newspapers reported it as occurring shortly before midnight on Friday, May 31. A funeral notice for Henry S. Cornell in the New York Herald confirms his date of death as May 31, as did the metal plate on his coffin.[10]

The incident at Cloud’s Mill captures the confusion and inexperience that marked the war’s early days. Likely a case of friendly fire, it exposed how hard it was to coordinate inexperienced troops in unfamiliar terrain and how quickly fear could turn fatal. For historians, it’s a reminder that every account deserves scrutiny.

M.A. Kleen is a program analyst and editor of spirit61.info, a digital encyclopedia of early Civil War Virginia. His article “‘A Kind of Dreamland’: Upshur County, WV at the Dawn of Civil War” was recently published in the Spring 2025 issue of Ohio Valley History.

Endnotes:

[1] William H. Price, “Civil War Military Operations in Northern Virginia in May-June 1861,” The Arlington Historical Society 2 (October 1961): 43-44.

[2] Patrick A. Schroeder and Brian C. Pohanka, eds., With the 11th New York Fire Zouaves in Camp, Battle, and Prison: The Narrative of Private Arthur O’Neil Alcock in the New York Atlas and Leader (Lynchburg: Schroeder Publications, 2011), 141; Frederic S. Isham, ed., History of the Detroit Light Guard: Its Records and Achievements (Detroit: Detroit Light Guard, 1896), 44; Nashville Union and American, June 6, 1861.

[3] Jean A. Beiro, A History of Cloud’s Mill in Alexandria, Virginia, edited by John G. Motheral (Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology Publications, 1986), 1-2.

[4] Edward T. Wenzel, Chronology of the Civil War in Fairfax County, Part I (CreateSpace: By the Author, 2015), 61-63.

[5] New York Tribune, June 9, 1861 and, June 12, 1861.

[6] Schroeder and Pohanka, 142.

[7] The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 7, 1861.

[8] John W. Bell, ed. Memoirs of Governor William Smith, of Virginia: His Political, Military, and Personal History (New York: The Moss Engraving Company, 1891), 28-29, 33.

[9] William B. Styple, ed. Writing and Fighting the Civil War: Soldier Correspondence to the New York Sunday Mercury (Kearny, NJ: Belle Grove Publishing Company, 2000), 25; New York Daily Herald, June 2, 1861.

[10] New York Daily Herald, June 7, 1861.

Thanks for the interesting article. Thanks for digging in so deep about this little know incident.

Thank you!

Enjoyed the article. I live close to that area how do I locate the marker? Thanks

Thanks, it’s located on North Paxton Street by some apartment buildings, GPS coordinates 38.814781, -77.123488

Thanks really appreciate it.