Newspaper Correspondence Advertisements: A Modernization of Courtship or a Lapse in Propriety?

ECW welcomes guest author Saanika-Jeet Dhillon.

Finding a husband or wife in antebellum America involved a complex set of traditions, expectations, and etiquette rules. In a respectable society which prioritized good social conduct among its young people, it was considered inappropriate to approach someone without a formal introduction from a suitable third-party, known to both individuals, according to an etiquette manual from 1856.[1] Courtship as a practice was structured and deliberate and often required young men and women to meet, court, and ultimately marry in accordance to strict social guidelines.

However, the outbreak of the Civil War disrupted this process. The physical separation of eligible young men from women seeking husbands created a major challenge to societal norms. It was initially expected that people wait until soldiers returned on furlough or were discharged or for the war to come to an end, but many young people were unwilling to postpone courtship indefinitely. With the distance presenting a major obstacle, soldiers and their potential sweethearts had to find new, novel ways to initiate relationships.

Enter the correspondence advertisement. Beginning in April 1863, prominent Northern newspapers such as the Chicago Tribune allowed soldiers to place short advertisements in which they described themselves and their intentions and outlined the qualities they sought in a wife. These advertisements arguably provided a more socially acceptable channel for courtship which could circumvent the physical limitations imposed by the war.

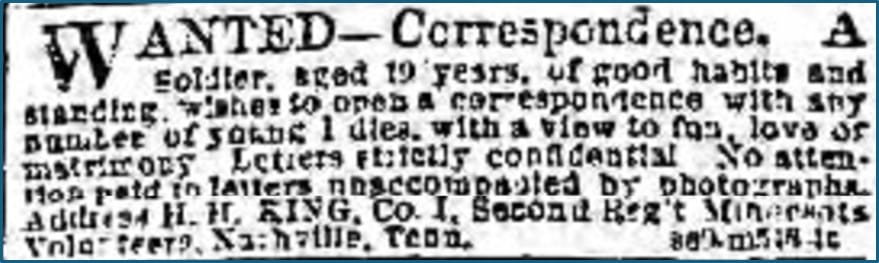

Many soldiers seemed to have made attempts to maintain a sense of propriety in their advertisements. For example, John W. and Willie M. requested that women enclose calling cards with their replies, seemingly a nod to antebellum etiquette.[2] A.B. Franklin advocated for a more gradual approach, stating that he hoped to cultivate a “reciprocity of feeling” which might develop into friendship and eventually marriage.[3] Others were more direct, such as H.H. King, who stressed that he was “of good habits and standing,” and Capt. C.S., who wrote that he sought a “partner for life.”[4] These examples suggest that soldiers were attempting to align this novel method of courtship with the social expectations of their time.

Women also began placing their own advertisements, outlining the qualities they sought in a husband. Education, intelligence, and the ability to provide for a household were emphasized, mirroring the expectations women held for their husbands before the war. In May 1863, Grace Greenwood and Gertie Hamilton stated that they wished to correspond with as many young gentlemen as possible, specifying that respondents “must possess an income sufficient for all practical purposes.”[5] These advertisements indicate that women were actively participating in this mediated courtship process while also maintaining their own standards for a suitable match.

Not all correspondence advertisements were entirely serious, however. Some soldiers treated them as a form of entertainment or as a way to pass the time during camp life. In January 1865, Bob Wilson and three of his friends described themselves in exaggerated terms as “75 years old, 15 feet high, dark complexions, yellow eyes, and…pug noses.”[6] This contrasted sharply with the more conventional ads of “gay and dashing young Cavaliers,” who genuinely sought marriage.[7]

Furthermore, some young women openly wrote of their willingness to correspond with many young gentlemen, which was a significant departure from the antebellum norms. This infers that the societal changes coming because of the Civil War were more than adapted courtship methods; young people could in theory court and write to multiple people at once, as writing letters was seen as less direct and intimate than meeting in person. In 1864, Lina Douglass and Gertrude Atherton asked, “How many gentlemen will respond? Don’t all come at once,” inferring that they were aware that they were likely to get multiple responses as correspondence ads had been used for a year by this point.[8]

These examples suggest that correspondence advertisements were not only a practical solution to wartime separation, but also a space where traditional social boundaries could be tested. While some Northern women and their communities considered the practice improper because it bypassed the traditional process of introductions, others saw it as a modernization of courtship that expanded opportunities for communication and connection.[9] After all, correspondence advertisements did open up possibilities for young people to exchange with others who were not from their hometowns, cities, or even states. These advertisements reveal a society in transition due to war, negotiating between longstanding social conventions and norms, and giving in to the pressures of wartime.

But what did the media think? Newspapers who published these correspondence advertisements inadvertently wound up as the unintended third party who “introduced” the courting couple.

In August 1863, the height of the popularity of correspondence advertisements in the Chicago Tribune, the editors of the newspaper published “Correspondence on the Brain,” an article in which they appeared to be amused by the practice.[10] They commented that one soldier claimed to have received over one hundred responses to his advertisement and joked that the advertisements would lead to more revenue for the post office “and a brisk demand for marriage licenses.”[11]

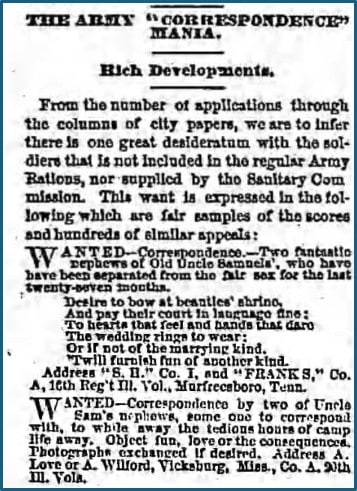

However, a mere two weeks later, the editors published “The Army Correspondence Mania,” and expressed their “disdain” for “indiscreet civilians,” specifically in relation to women placing advertisements in the newspaper.[12] They seemed to fear that soldiers were being taken advantage of by those wishing to dupe them. The tone changed significantly in this second editorial, as the newspaper decided to shift the blame for the actions of “persons of questionable character” away from “our boys in the army,” and emphasizing that many correspondence ads were inserted for nefarious purposes.[13]

It could be assumed that instances of duping were reported to the newspaper if they felt such a warning was necessary. Despite this, however, correspondence ads continued to run in the Chicago Tribune until the end of the war.

Ultimately, the growing prevalence of correspondence advertisements during the Civil War allowed for young soldiers away from home, and young women concerned for their futures, to try to navigate an uncertain time in their lives. Soldiers were not only risking their lives, but were also dealing with prolonged separation from their homes and families, and were prevented from engaging with the next step of their lives, marriage.

Correspondence advertisements allowed them to take some control back and to explore the field of courtship in the best way that was open to them. Young women were able to use correspondence advertisements to maintain agency in courtship, enabling them to set their own standards for their future husbands and to initiate communication. The use of correspondence advertisements served both practical and social functions, allowing courtship to continue despite the distance between couples, while also challenging the boundaries of propriety in a wartime society.

————

Saanika-Jeet Dhillon is a museum professional with a strong interest and background in American History, especially the social and gender history of the Civil War. She completed her MA in Museum Studies in 2025 from Syracuse University and received her MA in American History in 2022 from the University of Sheffield.

Endnotes:

[1] Anon, How to Behave: A Pocket Manual of Republican Etiquette, and Guide to Correct Personal Habits (New York, 1856), p.67.

[2] John W and Willie M, ‘Wanted – Correspondence,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 12 August 1863.

[3] A.B. Franklin, ‘Wanted – Correspondence,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 4 May 1863.

[4] H.H. King, ‘Wanted Correspondence,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 10 September 1863; Captain C.S., ‘Wanted – By An Army Officer,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 12 April 1864.

[5] Grace Greenwood and Gertie Hamilton, ‘Wanted – Correspondence,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 25 May 1863.

[6] Bob Wilson, Frank White, Charley Lang and Harry Case, ‘Wanted – Correspondence,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 28 January 1865.

[7] Gay Cavalier and Wild Doves, ‘Wanted – Correspondence,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago IL, 3 June 1863.

[8] Lina M. Douglass and Gertrude N. Atherton, ‘Wanted,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 21 April 1864.

[9] Patricia L. Richard, ‘“Listen Ladies One and All”: Union Soldiers Yearn for the Society of Their “Fair Cousins of the North”’ in Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller (eds), Union Soldiers and the Northern Home Front: Wartime Experiences, Post-War Adjustments (New York, 2002), p.144.

[10] ‘Correspondence on the Brain,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 12 August 1863.

[11] ‘Correspondence on the Brain,’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 12 August 1863.

[12] ‘The Army “Correspondence” Mania – Rich Developments’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 24 August 1863.

[13] ‘The Army “Correspondence” Mania – Rich Developments’ Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, 24 August 1863.