To Err is Human: Mundane Civil War Mistakes With Major Consequences (Part I)

If asked to list key mistakes of the Civil War, many probably would cite Robert E. Lee’s decision to launch Pickett’s Charge, Ulysses S. Grant’s Cold Harbor attack, William S. Rosecrans’s inadvertent creation of a gap in his Chickamauga battleline, or Daniel Sickels’s forward movement at Gettysburg. All represent “big” mistakes, resulting in significant casualties or other patently important results.

Yet the war offers a bounty of other mistakes that, while on their face might seem trivial, also caused significant consequences. These range from mere clerical errors or unfortunate turns of phrase to other seemingly minor miscues. But all played an outsized role in how the Civil War or its telling unfolded. Here are some of these more “mundane” errors that mattered.

An administrative error results in a consequential Civil War nickname

Named at birth Hiram Ulysses Grant, the young man destined to enter West Point feared that his initials would lead to the unwelcome nickname “HUG,” a moniker already used to tease him. Grant thus generally used Ulysses as his first name. The congressman responsible for Grant’s Military Academy application paperwork therefore “knew” his nominee’s first name, but mistakenly assumed that his middle name must be for his mother, nee Simpson; thus—despite Grant’s protest when arriving at the Academy—the name “Ulysses S. Grant” was assigned the new plebe.[1] Grant initially resisted the error, as shown when Cadet Grant signed a letter to a cousin “U.H. Grant.”[2] Ultimately, however, Grant accepted the dictate of Army bureaucracy.

The congressman’s error assumed national renown in February 1862 when then-Brig. Gen. Grant demanded the “unconditional and immediate surrender” of Fort Donaldson. This first major Union victory rocketed “U.S.” Grant to fame as “Unconditional Surrender” Grant. Lincoln promptly approved Grant’s promotion to major general. Grant’s star burst upon the national scene, aided by a nickname born of error.[3]

A newspaper typo creates a war hero

Knowing that newspapers were handing out nicknames to military leaders, would you rather be tagged with “Granny” or “Fighting”? Lee briefly acquired the former nickname,[4] while Joseph Hooker permanently achieved the latter, purportedly due to a newspaper typo. The legend is that a reporter intended to write a story headlined “Fighting,” followed by a period, the next line starting “Joe Hooker.” But when the period was lost in transmission a memorable martial nickname was born.[5]

An unfortunate turn of phrase frustrates a general’s strategy

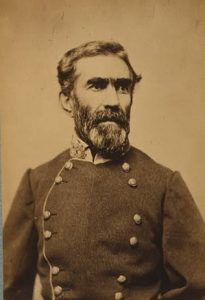

Not every error simply led to a nickname. Sometimes a mere mistaken choice of words impacted a battlefield. Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg learned this lesson to his dismay.

On September 10, 1863, Bragg was poised to deliver a savage blow to U.S. Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland. The Confederate hammer was to fall at a point ten miles south of Chattanooga, Tennessee. The opportunity arose because, following Bragg’s evacuation of that city, an overconfident Rosecrans split his army to pursue, through mountainous terrain, what Rosecrans believed were demoralized Confederates. On September 9 part of Rosecrans’s army, a 6,000-man division under Maj. Gen. James Negley, found itself alone in a valley called McLemore’s Cove. Bragg prepared a trap. Bragg moved an overwhelming force—at one point holding a six-to-one advantage—to converge on Negley. While Negley was reinforced to 10,000 men, that only served to increase the number of U.S. soldiers about to be killed or captured. All that was needed was for the local Confederate commander to attack, triggering what was at that point still a three-to-one manpower advantage against an isolated enemy force that had no easy means of escape through confining mountains.[6]

A problem was that CSA Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman, charged with leading the assault, was nervous. Hindman, positioned north of Negley, did not like being in McLemore’s Cove. He was afraid that U.S. troops well to his own north might trap him. Hindman proposed to Bragg that he (Hindman) attack north to clear the supposed threatening U.S. troops.[7]

Bragg knew that Hindman faced no threat. Meanwhile, Bragg had 30,000 men in position to smash Negley’s 10,000. Yet Bragg replied to Hindman in words that virtually ensured that Bragg would lose his golden opportunity. On September 10 Bragg wrote: “General Bragg orders you to attack and force your way through the enemy to this point at the earliest hour that you can see him in the morning.”[8]

“[F]orce your way through the enemy to this point…” Those were not words that assured Hindman that he was on the verge of victory over a trapped and overmatched foe. Rather, that language convinced Hindman that it was he who was trapped and needed to fight (“force”) his way out. Indeed, Hindman later explained that “My construction of the above-quoted dispatch was that the general commanding considered my position a perilous one, and therefore expected me not to capture the enemy, but to prevent the capture of my own troops, forcing my way through to La Fayette, and thus saving my command…”[9]

Hindman froze. Negley finally realized his vulnerable position and escaped. Bragg lost his chance to crush a portion of Rosecrans’s army because of a badly chosen turn of phrase. A simple difference in the wording of Bragg’s order might have emboldened Hindman and spurred him to launch an attack that could have altered the course of the war in the West. [10]

[1] Ron Chernow, Grant (Penguin Press, New York, NY, 2017), pp. 3-4, 17-20; Joan Waugh, U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 2009), pp. 13, 19, 20, 21.

[2] “Ulysses S. Grant to R. McKinstry Griffith, September 22, 1839,” Cadet Ulysses S. Grant at West Point, 1839, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/cadet-ulysses-s-grant-west-point-1839.

[3] Chernow, pp. 182, 185-186; Waugh, pp. 54-55; Bruce Catton & Oscar Handlin (Ed.), U.S. Grant and the American Military Tradition (Little, Brown and Company, Boston, MA, 1954), pp. 78-79.

[4] ‘Confederate Legend Robert E. “Granny” Lee Embarrassed at Cheat Mountain,’ American History Central (September 12, 2025), https://www.newsbreak.com/american-history-central-1605007/4230087583856-confederate-legend-robert-e-granny-lee-embarrassed-at-cheat-mountain-true-civil-war; Gary W. Gallagher, ‘“Old Brains” and “Granny Lee,”’ History Net (March 31, 2021), https://www.historynet.com/old-brains-and-granny-lee-civil-war-soldiers-often-gave-their-generals-pointed-nicknames/.

[5] However, the legend has been challenged. Edward Alexander, ‘Joe and the Illini: The Unclear Origins of Two “Fighting” Nicknames,’ Emerging Civil War (October 15, 2025), https://emergingcivilwar.com/2020/10/15/joe-and-the-illini-the-unclear-origins-of-two-fighting-nicknames/.

[6] Earl J. Hess, Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 2016), pp. 153-157; Steven E. Woodworth, Jefferson Davis and His Generals: The Failure of Confederate Command in the West ( University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1990), pp. 230-231; Donald R. Jermann, Civil War Battlefield Orders Gone Awry: The Written Word and Its Consequences in 13 Engagements (McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2012), pp. 141-148; Mark M. Boatner, The Civil War Dictionary (David McKay Co., Inc., New York, NY, 1988), p. 584.

[7] Hess, p. 155; Jermann, p. 147.

[8] Jermann, p. 147 (emphasis supplied), quoting The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I, Vol. XXX, Pt. 2 (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1880-1901), pp. 294-295, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hwannj&seq=299 (hereafter “OR”).

[9] OR, Ser. I, Vol. XXX, Pt. 2, p. 295.

[10] Hess, pp. 155-156; Jermann, pp. 147-148; see also infra, footnote 6.

Great post, Kevin. ASlways enjoy reading your articles.

Brian, thank you.