Echoes of Reconstruction: Black Citizenship: Frederick Douglass & An Immigrant Professor Confront President Johnson

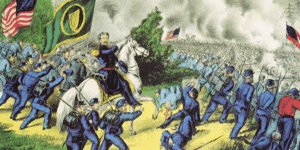

The Union Army that triumphed in 1865 reunited the United States by military force. The composition of that army served notice that old ideas about who was and who was not an American were collapsing. More than one-third of all Union soldiers were Black or foreign-born. Six out of ten men in the Union navy came from those two groups. Conversely, nearly all of the defeated Confederates, viewed as traitors by many adherents of the United States, were native-born whites. [1]

The 14th Amendment that emerged from the Civil War struggle would codify revolutionary changes in citizenship for African Americans and immigrants alike. [2]

Less than a decade earlier, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court wrote in the Dred Scott decision that Blacks were not citizens and that Blacks “had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect…” In the same years, the Know Nothing movement was campaigning to deny citizenship rights to immigrants and Catholics and to their United States-born children. [3]

The formation of Irish regiments in the Union army, complete with Irish flags and folkways, did not just provide the comforts of ethnic solidarity to immigrant soldiers. The regiments also served as a challenge. In the 1850s, these very symbols of foreignness had been stripped by Know Nothing governors from Irish militia companies. During the Civil War the once despised flags had been advanced in battle at great sacrifice to the immigrant men who bore them and to the cheers of native-born soldiers who shared the same fields of death. [4]

Union soldiers campaigning in the South often found that the only Southerners who were loyal to the Union were the Blacks they encountered as slaves on plantations. The enslaved African Americans offered encouragement, passed on intelligence about the location of Confederate units, and helped Union soldiers who had been taken prisoner escape to the North. When Blacks were finally allowed to enlist in the army, they joined by the tens of thousands. [5]

And yet, at the end of the war, African Americans who had supported the United States government were still not considered citizens in many states while white men who had taken up arms against the United States were not only citizens, but voters. [6]

While some in President Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party argued that Blacks and immigrants had equal rights with native-born whites, the president’s Attorney General Edward Bates concluded after much research that the Constitution was ambiguous on most questions concerning citizenship. Neither Blacks nor immigrants could feel secure in their citizenship and neither could their children. [7]

Francis Lieber, a German immigrant and one of the foremost legal scholars in America, argued that new amendments needed to be added to the Constitution to protect the rights of newly freed slaves. He understood that this approach would be difficult because many native-born Americans seemed to view the Constitution and the Bill of Rights as almost divinely inspired and not subject to change. Lieber saw this notion of Constitutional inerrancy as directly opposed to the view of the Founding Fathers themselves. As great as the Founders may have been, he argued in a widely distributed essay, they understood the “probability of necessary amendments.” Their genius was in understanding that their great work might need modification over time for the country they founded to endure. [8]

In the last months of the Civil War, Lieber wrote that the United States was in “a time of necessary and searching reform.” The law had to recognize that the facts on the ground had been changed by the war and the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. “Things have already changed,” he wrote, and “we cannot avoid its duty.” [9]

As an immigrant, Lieber was less susceptible than the native-born to the white supremacist civic religion, a time when many whites believed, as he wrote, the “unhistorical fact that the Government of the United States was established by the white people alone” and had then reached the “illogical conclusion [that the government] is for the white people alone.” This convenient illusion allowed whites to govern Blacks as an inferior race. Lieber, who had years earlier owned slaves himself, declared that “it is impious to withhold from a race the common benefits for which governments are established.” He wrote that Blacks were entitled to “justice and protection” from the government on a basis equal to whites. [10]

To correct this imbalance, Lieber proposed a constitutional amendment granting citizenship to everyone born in the U.S. or naturalized “without any exception of color, race, or origin…” [11]

Lieber and others also understood that a major flaw in the Constitution was that it did not explicitly extend to the protections of the Bill of Rights to protect citizens against abusive actions by the state governments. This may seem almost impossible to believe today, when state and local governments are often called to account for violating people’s Constitutional rights. However, if we look at the language of the First Amendment, for example, we see that it says that “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press…” It does not say that the State of South Carolina shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech. [12]

During the decades before the Civil War, many Southern states adopted laws restricting freedom of speech when the subject was slavery. John Bingham, who was to be one of the principal authors of the Fourteenth Amendment, pointed out before the war that in areas where slavery was legal, it was often illegal to speak out against slavery. Severe punishment was meted out particularly to anyone who criticized slavery to enslaved Blacks or encouraged them to resist their enslavement. [13]

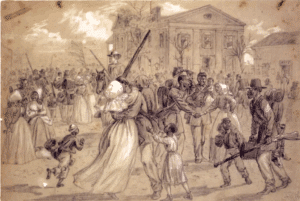

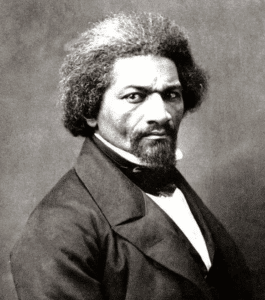

On February 7, 1866 Frederick Douglass led a delegation of 13 representatives of the National Convention of Colored Men to the White House to meet with President Andrew Johnson, to discuss the necessity for Blacks to be recognized as American citizens. Douglass told Johnson that Lincoln had placed the sword in the hand of the Black man to “assist in saving the nation” when he recruited the 180,000 Blacks in the United States Colored Troops. Now, Douglass said, Blacks asked that Johnson “place in our hands the ballot with which to save ourselves.” [14]

Johnson’s response must have shocked his listeners. He told them “I do not want to adopt a policy that I believe will end in a contest between the races, which if persisted in will result in the extermination of one…” In other words, he was predicting a race war if Blacks were made citizens. Johnson said that Blacks had gained much by being freed from slavery, and whites had lost much by being deprived of their slaves. He argued that it would be unfair to whites, who had lost so much already, to also lose the power to be the sole governing race in the United States. [15]

Since a majority of white Southerners opposed giving Blacks the vote, President Johnson said:

“I should consider it would be tyrannical in me to attempt to force such upon them without their will. It is a fundamental tenet in my creed that the will of the people must be obeyed. Is there anything wrong or unfair in that?”

“A great deal that is wrong, Mr. President, with all respect,” responded Douglass. [16]

Immigrants from Union general Carl Schurz to former-Congressman Robert Dale Owen would conclude with Frederick Douglass that the only way to establish citizenship rights for freed slaves and immigrants was through the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment. [17]

Resources:

The Transcript of the meeting between Frederick Douglass and Pres. Andrew Johnson is available here.

Sources:

1. DRED SCOTT v. SANDFORD, 60 U.S. 393, 396 (1856); American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment by Gerard N. Magliocca published by NYU Press. (2013) Kindle Edition; Democracy Reborn: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Fight for Equal Rights in Post-Civil War America Garrett Epps published by Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition; A Letter to Senator E.D. Morgan on the Amendment of the Constitution Extinguishing Slavery by Francis Lieber published by Loyal Publication Society (1865); Amendments of the Constitution Submitted to the Consideration of the American People by Francis Lieber published by The Loyal Publication Society (1865); Transcript, Meeting between President Andrew Johnson and a Delegation of African-Americans, White House, February 7, 1866; Becoming American Under Fire: Irish Americans, African Americans, and the Politics of Citizenship During the Civil War by Christian G. Samito published by Harvard University Press (2009); The Fourteenth Amendment and the Priviledges and Immunities of American Citizenship by Kurt Lash published by Cambridge University Press (2014); No State Shall Abridge: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights by Michael Kent Curtis published by Duke University Press (1990).

2. Democracy Reborn: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Fight for Equal Rights in Post-Civil War America Garrett Epps published by Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition

3. DRED SCOTT v. SANDFORD, 60 U.S. 393, 396 (1856)

4. Becoming American Under Fire: Irish Americans, African Americans, and the Politics of Citizenship During the Civil War by Christian G. Samito published by Harvard University Press (2009).

5. Becoming American Under Fire: Irish Americans, African Americans, and the Politics of Citizenship During the Civil War by Christian G. Samito published by Harvard University Press (2009).

6. Becoming American Under Fire: Irish Americans, African Americans, and the Politics of Citizenship During the Civil War by Christian G. Samito published by Harvard University Press (2009).

7. Becoming American Under Fire: Irish Americans, African Americans, and the Politics of Citizenship During the Civil War by Christian G. Samito published by Harvard University Press (2009).

8. Amendments of the Constitution Submitted to the Consideration of the American People by Francis Lieber published by The Loyal Publication Society (1865) pp. 3-6.

9. Amendments of the Constitution Submitted to the Consideration of the American People by Francis Lieber published by The Loyal Publication Society (1865) pp. 3-6.

10. Amendments of the Constitution Submitted to the Consideration of the American People by Francis Lieber published by The Loyal Publication Society (1865) pp. 10-16.

11. Amendments of the Constitution Submitted to the Consideration of the American People by Francis Lieber published by The Loyal Publication Society (1865) p. 89.

12. American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment by Gerard N. Magliocca published by NYU Press. (2013) Kindle Edition

13. American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment by Gerard N. Magliocca published by NYU Press. (2013) Kindle Edition pp. 44-46.

14. Transcript, Meeting between President Andrew Johnson and a Delegation of African-Americans, White House, February 7, 1866

15. Transcript, Meeting between President Andrew Johnson and a Delegation of African-Americans, White House, February 7, 1866

16. Transcript, Meeting between President Andrew Johnson and a Delegation of African-Americans, White House, February 7, 1866

17. Democracy Reborn: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Fight for Equal Rights in Post-Civil War America Garrett Epps published by Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition

To the collective horror of most of us, we are now back to a worse administration than that of Andrew Johnson. Only now, the levers for institutional abuse seem much stronger than they did in the 1860s.

There are Echoes of Reconstruction today!

That explains three consecutive crushing victories for Trump. Americans are sick of the racism and repression of Obamaism-Bidenism, and wanted their Constitutional rights and birthright back.

This blog site should not be used as a political platform or as vehicle to espouse crass political statements. The nebulous, sweeping and factually unsupported statement “To the collective horror of most of us …” is utterly ridiculous and should not be welcomed in this or any other platform whose goal is to stimulate thoughtful and credible discussion on a topic participants are very passionate about. I imagine that myself and others are not interested in this. Please leave the sycophantic idealogical statements out of these discussions. They are not constructive and do not provide any positive contribution.

Kudos to Mr. Klassen for his brilliant statement and sentence:

‘The nebulous, sweeping and factually unsupported statement “To the collective horror of most of us …” is utterly ridiculous and should not be welcomed in this or any other platform whose goal is to stimulate thoughtful and credible discussion on a topic participants are very passionate about.’

Well done, sir!

Thanks Mr. Schafer. I appreciate that. Take care.

What an amazing opening paragraph! How fascinating that a US Army, not its people or Government representatives, determined – “served notice” – who was and was not an American – something that just this week the Supreme Court declared an illegal act; that a huge percentage of this army was not American (“agrarian mercenaries” – Albert Sydney Johnston) and well more than half the associated navy were not American; and that they had a “view” – note, not the legal right, but just an opinion – that at least one-fifth of the population, who were “native-born whites,” were traitors, e. g. deserving of disenfranchisement and death. Gosh. Golly. Gee. With mind-blowing facts like this in hand, folks whose grandfathers had fought against British troops and the mercenaries they brought to America to propagate the exact same view, might get the idea that some sort of Replacement Program was at work – funded, incidentally, by the very taxes and constitutionally-banned internal tariffs they were being forced to pay.

The piece then goes on to fasten upon the sensationalist aspect of President Johnson’s statement, whilst conveniently ignoring the legal basis on which he stood, playing that tried and true strategy, the “Race Card.” Whatever one may think about the racial views of the President or whomever else for that matter – including the overwhelming percentage of Northern Whites, who did not want freed slaves moving to their states, or being allowed to vote no matter where they resided, and kept in place their pre-war laws, “The Black Codes” for decades, though this is never mentioned, except to call out Southerners for using the exact same Codes, though in the South they were called “Jim Crow” – the legal facts of the matter were that a single political party in the U.S. was demanding that Johnson enforce their political demands on U.S. citizenry, the Constitution be damned. Having duly elected representatives writing a Bill, voting it into Law, and then an Amendment to the Constitution if necessary, is how things are enforced in America; enforcement is not supposed to be at the point of a gun or bayonet – like it was done in Europe.

Boy, it’s just amazing how people will behave when they’re raised to believed in a form of government – and then it’s suddenly taken away from them by people who have control of an army.

While many soldiers of the Union Army were “foreign born” that does not mean that they were not Americans. They were naturalized citizens. The Black men who served in the Civil War were Americans. Indeed large numbers of black men had served in the US Navy since the Revolution. They fought for their country, a country that offered a working man opportunity, the protection of the law, and a say in their own government.

The form of government of the South remained the same. Who got to participate in that system changed. And that was what rankled.

Mainly, no. The vast majority of the “foreign-born” members of the Federal military were legally foreigners, and had not been naturalized. It is truth, not legend, that ships full of Irish immigrants were met at the docks in Boston, New York and Philadelphia and men of the appropriate age and fitness were taken right off the boat, put into uniforms and handed guns, and marched off to the Army. So quickly were they sent into service that there are countless testimonies from them that they were sent into battle without having ever fired their muskets or rifles. Vast numbers of Germans in the Federal army didn’t speak a word of American.

As for changes in government, anyone is rankled when they have rights, and then those rights are taken away for no reason other than to control them. Oddly, though, you somehow failed to mention that no changes were allowed in the government in Northern states, or in their representatives sent to Washington. No, those state assemblies and in the House and Senate still only had white men – blacks somehow managed to serve in these roles in the South. Nor were women allowed to vote. Nor were the Black Codes struck down in the North. Let’s see, how many more years were schools segregated in Boston? 100 was it? Clearly, “the changes were for thee, not for me.” Yeah – inequality rankles.

You have zero sources for your assertions. Phrases like “vast majority” are meaningless.

As far as the German immigrants were concerned, they knew enough not to approve of slavery and to be true to the Union, which is more than many a Virginia blue blood, obsessively tracing his family tree to Pocohantas could figure out. An American isn’t bred like a dog. Its something you do as well as something your grandfather was.

Poor A. S. Johnson, bleating that the Yankees were mercenaries, when his whole cause was a deluded lurch to hang onto property and privilege.