When Mexican Troops Fought with the Union in Texas

Over the course of his life, Juan Cortina fought against the U.S. Army, did civilian contract work for the Army, overthrew an American town, fought the Army again, traded with the Confederates, received military supplies from the U.S., traded with the Confederates again, led the only foreign military unit that fought with the Union during the Civil War, had active-duty U.S. troops fight for his cause in Mexico, then fought the Army once more.

That may make him sound like a turncoat, but Cortina had the best interests of his native Mexico in mind. France invaded his homeland in 1862, and Cortina used whatever party happened to be across the border to seek advantages.Cortina served in various roles from bandit to politician to general, and it was this latter title by which he led Mexican troops in combat alongside Federal forces.

By the summer of 1863, Confederates in the far west faced dire supply issues as the blockade tightened and the fall of Vicksburg placed the Mississippi in Union hands. One remaining source of supply was trade over the border with Mexico. Cotton from as far as Arkansas slipped across the Rio Grande to Mexican towns such as Matamoros and Bagdad, as war materiel passed to the opposite side.[1]

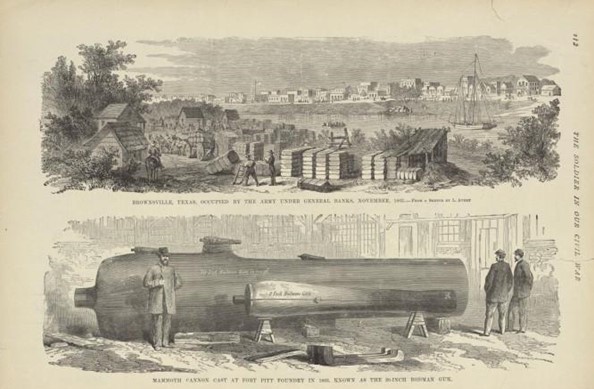

In late 1863, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks moved to intercept this trade. Cortina watched across the border in Matamoros as Union troops marched on Brownsville.[2] At this time, he was the de facto commander of the province and controlled the town’s lucrative customs house revenue. Cortina sent over $85,000 (1.4 million today) in customs duties to Mexican President Benito Juarez to fund the war effort.[3]

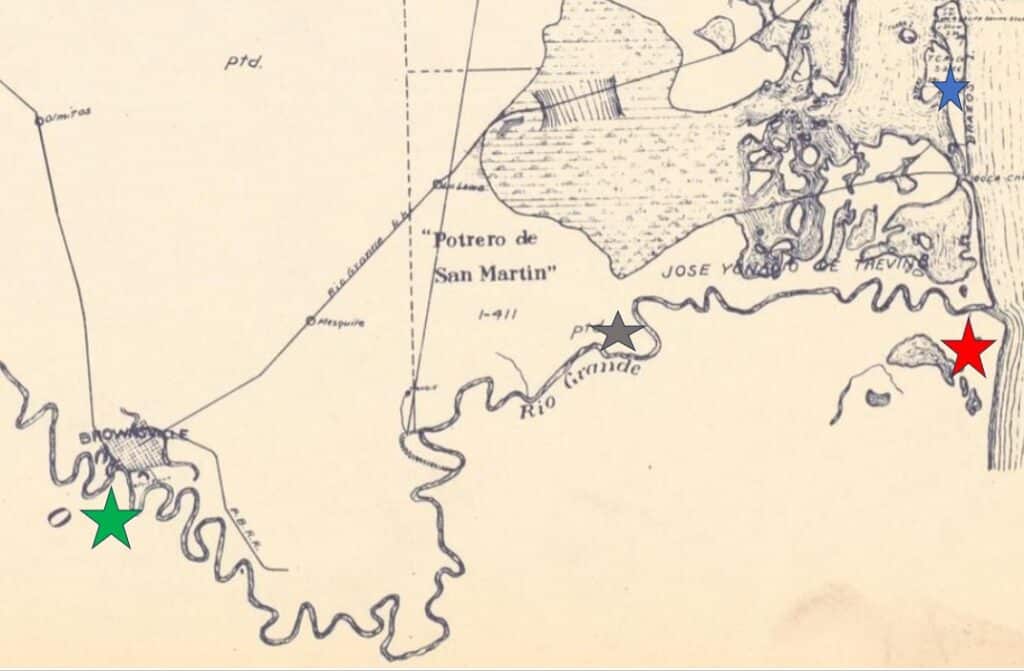

Cortina opened talks with the Union forces and maintained cordial relations despite allowing the rebels to continue trading upriver. Ultimately, the Union abandoned Brownsville, most heading to Louisiana to conduct the Red River Campaign, but still holding a presence on Brazos Island. Cortina met with Maj. Gen. John McClernand, now in charge of the neighboring Union forces, in April 1864. In exchange for stopping the cotton trade, McClernand gifted Cortina ten artillery pieces.[4] Cortina assured his ally, “I will do everything that tends to the good and prosperity of the American Union.”[5]

Yet the French continued to gain ground, and Cortina saw fit to resume the flow of goods so as to aid his countrymen. In late August, French Imperial forces landed at Bagdad, while another force marched toward Matamoros from the country’s interior.[6] Cortina planned to move part of his command across the border and seize Brownsville, joining the Federals who would advance from Brazos Island. Many of his subordinates disapproved, but he claimed they were going to attack the French downriver after this maneuver. Union leadership did not directly endorse the plan, but tells him he would be welcomed on the American side and could retain command over his force.[7]

On September 3, Cortina again closed the cotton trade with the Confederates.[8] Two days later, some of his force established gun emplacements across the river from a rebel camp at Palmito Ranch.[9] The Confederates already received warnings of a possible crossing from sources close to Cortina’s staff.[10][11]

The following morning, Colonel H.M. Day of the 91st Illinois moved off Brazos Island, making his way to the ranch with 900 infantry. As they engaged the rebels, six guns of Cortina’s artillery bombarded the 4th Arizona Cavalry, striking their flank.[12] Nevertheless, the Confederates held their position against the artillery until the afternoon when they fell back seven miles to Brownsville. Cortina and over 300 soldiers of his brigade crossed the river that day unbeknownst to their Union allies, and encamped near the Texas town.[13]

Brigadier General John “Rip” Ford could only gather 300 men in Brownsville, but putting on a performance, he marched them around in view of Matamoros to appear much stronger. Ford armed the citizens as best he could. Gathering most in the town’s fort, they feared being surrounded by the Yankee and Mexican forces.[14] The Federals bivouacked that night at Palmito Ranch.[15]

On the 8th, Col. Day wrote to higher-ups in the Department of the Gulf that Cortina was on the American side, fleeing from the concentration of French forces. Day dispatched a message to Cortina saying that he is welcome to seek refuge stateside, but, in a departure from the previous plan, his troops must surrender their weapons and ammunition.[16]

On Sept. 9th, the 1st (US) Texas Cavalry greeted the Mexicans at Palmito Ranch, who laid down their arms in compliance. While the surrender was ongoing, they came under attack by Confederates, who encircled them on three sides. The Federals rearmed the Mexicans, who hid with them in the chaparral and whittled away with musketry fire, holding their position for several hours against two attacks. Rebel cavalry rode in from the town, and these fresh troops attacked the Federal center, forcing the Yankees and Mexicans into a retreat of several miles. After small skirmishes in the following days, the joint force fell back to Brazos Island.[17][18][19]

The Union’s Department of the Gulf warned Day that if Cortina tried to make war against the French from the American side, Day was to consider Cortina as an enemy.[20] However, Maj. Gen. Edward Canby decreed that the Mexicans were eligible for enlistment in the regular U.S. Army, although they would not be used for service in the border region.[21] Federal authorities at Brazos again disarmed the 303 Cortinistas present, and several enlisted in Federal forces. Most went back to Mexico to continue service under their general, receiving their armament back before crossing the border.[22]

The graycoats now held the border from Brownsville to the gulf. Casualty numbers differed; the rebels claimed over 100 Mexicans and Union soldiers were killed and wounded, and that none of their men were killed. Colonel Day felt assured that great numbers of his adversary became casualties, but Rip Ford only reported two or three killed, a few wounded, and three missing.[23]

Ford saw this cooperation as “unprovoked and unwarranted”.[24] He wrote to Day asking about the status of twelve Mexican prisoners he captured, inquiring “if they were at the time of capture in the service of the Government of the United States?” The Union colonel replied he had “the honor to state that those men were in the service of the United States and fighting under the U.S. flag.”[25] This was a legal defense against what would otherwise be a breach of international law and potentially an act of war.

The French were equally furious that the Federals aided Cortina. Confederate Brig. Gen. James E. Slaughter opened negotiations with the Imperials at Matamoros to solicit aid in case Cortina attacked again. General Tomás Mejía agreed to send his cavalry, in civilian dress, to defend Brownsville if the need arose.[26] With Union forces in Texas reduced to just 950 at Brazos Island, the remainder of the war on this front passed relatively peacefully until the final battle of the conflict at Palmito Ranch.[27] This transnational cooperation stands as perhaps the only example of a foreign unit engaging in American Civil War combat, and illustrates the unpredictability of the war in the borderlands.

[1] M.M. McAllen, “Life Lived Along the Lower Rio Grande During the Civil War,” in Civil War on the Rio Grande, 1846-1876, ed. Roseann Bacha-Garza, Chistopher L. Miller, Russell K. Skowronek (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2019): 61-65.

[2] Jerry Thompson, Cortina: Defending the Mexican Name in Texas (College Station, Texas A&M University Press, 2013), 110-111.

[3] William S. Kiser, Illusions of Empire: The Civil War and Reconstruction in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 140.

[4] Kiser, 140.

[5] Cortina to John A. McClernand, April 7, 1864, OR Vol. I, Series 34, Part 3, 73-74.

[6] Stephen A. Townsend, “The Rio Grande Expedition 1863-1865” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Texas, 2001): 195. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc2744/

[7] Thompson, 141.

[8] Robert L. Kerby, Kirby Smith’s Confederacy: The Trans-Mississippi South, 1863-1865 (New York and London, Columbia University Press, 1972), 370.

[9] Townsend, 198-199.

[10] Ford to Dwyer, OR, Series 1, Vol. 41, Part 3, 909.

[11] OR, Series 1, Vol. 41, Part 3, 912.

[12] Kerby, 370.

[13] Thompson, 143.

[14] Townsend, 199.

[15] Kerby, 370.

[16] OR, Series 1, Vol. 41, Part 3, 99-100.

[17] Thompson,143.

[18] H.M. Day to George B. Drake, September 18, 1864, OR, Series 1, Vol. 41, Part 3, 184-185.

[19] John Salmon Ford, Rip Ford’s Texas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1963), 374.

[20] Townsend, 201.

[21] Edward Canby to Nathaniel Banks, OR, Series 1, Vol. 41, Part 3, 197-198.

[22] Thompson, 144.

[23] Thompson, 144.

[24] Thompson, 140.

[25] OR, Series 1, Vol. 41, Pt. 3, 947.

[26] Jeffrey WM Hunt, The Last Battle of the Civil War: Palmetto Ranch (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), 83.

[27] Kerby, 371

I was a teacher in California when I began doing genealogy and tracing my line to Civil War soldiers. In conversing with one of my colleagues who happened to have Mexican heritage, he told me his family were U.S. Citizens because one of his ancestors joined a Union regiment during the Civil War and was thus given citizenship. I never followed up on the story unfortunately.

Wow! That’s very interesting to me. There’s tons of Hispanic last names in Texas regiments, Union and Confederate, but really no way to tell whether they came from Mexico or stateside. I’d love to get a roster of Cortina’s brigade, or find out what happened to those 12 prisoners, but have had no luck so far. Do you have anything to go off of, even a last name?

This is very interesting article Thanks for the research into this little known history.

You’re welcome! I’m glad you enjoyed it. My best guess as to why this subject isn’t talked about much is that outside the cotton trade, none of this has any bearing on the war as a whole. And if you think everything happening in this part of Texas is complicated and difficult to track down, multiply that tenfold for the other side of the Rio Grande.

Very enlightening. Very informative article about the United States relationship with Mexico, specifically Cortina, during the Civil War.

Thanks, glad you liked it!

Thanks Aaron … terrific story about a little known and rather odd theater of CW.

So many peculiarities with this theater! Glad you liked it.