Maternal Gettysburg

ECW welcomes guest author Sarah Traphagen.

War hath no fortitude like a mother determined. Artillery and bullets be damned.

Recently, I taught a course about women at the battle of Gettysburg. What moved me now as a mother that I did not have the perspective for prior to becoming one was the intense, focused mothering that occurred during the collision at the Pennsylvania crossroads.

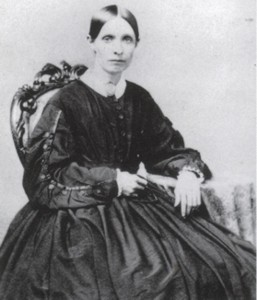

No doubt countless Gettysburg mothers’ stories are untold. The women I note here are, thankfully, known to history. Mary Wade lost her daughter, Jennie, in the battle, and Sarah Broadhead published a diary she kept from June 15 to July 15, 1863. At first glance, their mothering under fire in their stories appears expected, mundane even. However, studying Mary’s and Sarah’s ability to execute the ordinary in extraordinary circumstances conveys the limitless nature of human endurance – a mother’s endurance – and should be elevated in the narrative of our nation’s most pivotal moment.

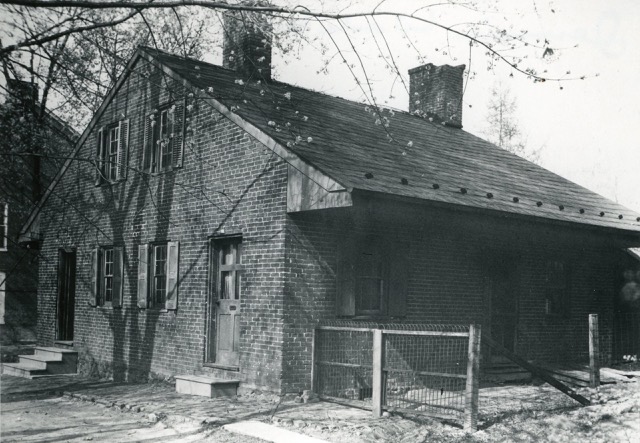

548 South Baltimore Street

Mary Wade, her two daughters Georgia and Jennie, her youngest son Harry, and another little boy who boarded with the family, Isaac, sheltered in a brick double home near Cemetery Hill as the battle raged. The northern half of the home was rented by Georgia and her husband, John McClellan, away with the 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry.[1] Mary held the center of the children’s orbit throughout.

As Jennie baked bread for soldiers and the boys helped with chores, Georgia recovered from childbirth. Mary had aided a doctor in the June 26 delivery of her grandson, and no doubt both she and Georgia were exhausted.[2] Georgia, snug in a bed placed in the parlor, cared for her newborn in the natural tumult of postpartum life – minimal sleep, physical discomfort, likely breastfeeding, and responding to crying. Mary cared for them all as 150 bullets and an unexploded ten-pound shrapnel shell barreled into the house.[3]

Citation: “Black and white photograph of a brick house which is now the Jennie Wade Museum,” photograph, 5604.041, Adams County Historical Photographs, Adams County Historical Society, Gettysburg, PA.

The home absorbed extensive fire, being situated between Confederate sharpshooters nearby and Union pickets outside its walls. July 2 brought the misdirected shrapnel shell, which “penetrated into a plaster wall that divided the double dwelling” and came to rest cold, miraculously. [4] Night offered little relief from the ammunition. Pitch-black and terror encircled Mary and her children as they huddled wide awake in the parlor. Mary’s nerves must have been frayed, her heartbeat rapid, and her desire to protect her children and grandchild surging. Fierce though she was, she could not stop death’s call upon her family.

One bullet came mighty close to Georgia and her baby; another found Jennie. On the morning of July 3, a bullet “entered the front room and struck the bedpost, then hit the wall, and finally fell…onto the pillow at the foot of [Georgia’s bed].” Shortly after, Jennie lay flour-dusted and dead on the kitchen floor with a spent bullet lodged in her corset. Mary heard the bullet’s trajectory and turned from tending a fire to see her child fall. She did not fall apart. She quietly informed Georgia.[5]

Georgia shrieked in horror (was the baby startled?), ushering in Union soldiers. They instructed the women and boys to go into the neighbor’s cellar. The unexploded shell proved to be an ironic lifeline: it created a hole in an upstairs wall, which gave them internal access to the dwelling’s other half. None of them would have to risk exposing themselves to direct fire. Selfless, Mary sent Georgia and her little one first through the hole followed by the boys. With the help of the soldiers, they passed through the opening, went down the stairs of the adjoined home, snuck out, and descended into safety. Adamant as iron, Mary would not go without all of her children. Jennie’s body came with her.[6]

Eighteen hours passed before the battle’s end. Mary did not stay in the cellar the whole time. Putting herself at risk and carrying the weight of Jennie’s loss and Georgia’s discomfort, she went to the kitchen stained with her child’s blood and baked fifteen loaves of bread for the soldiers who helped.[7] This striking image juxtaposes the equal simplicity and atrocity of the demand on her. She mothered those hungry boys, too. Nothing could have stopped her but another bullet.

217 Chambersburg Street

Sarah Broadhead lived with her husband, Joseph, and their four-year-daughter, Mary, in the end unit of a two-story brick row house on the western side of Gettysburg.[8] Her battle story is one of ups and downs as she and her daughter descended in and out of cellars until the Union claimed victory. Throughout the fray, Sarah managed to embody calmness, think ahead, make meals, and do laundry – all while famished, sleep deprived, and emotionally present for a child.

Sarah was fortunate to have her husband at home for the battle’s duration, but she was on her own with Mary on June 26 as both armies, especially the Confederates, settled in. They were “entirely alone, surrounded by thousands of ugly, rude, hostile soldiers, from whom violence might be expected.” [9] Such a threat exacerbated her anxiety, yet Sarah stayed calm and protective. 217 Chambersburg Street remained unscathed in the days leading to July 1.

Not only did she maintain steadiness as battle was imminent; she devised a plan for feeding her family and made it come to fruition. On the battle’s first day, she rose early to bake. Like many women in town that morning, she mixed, kneaded, and waited. “I had just put my bread in the pans when the cannons began to fire,” she wrote. The concussive action eventually became unbearable, prompting her to shelter with Mary in a neighbor’s cellar. Internally uneasy, sleep eluded her that night.[10]

July 2 pushed the Broadhead family into another cellar nearby. Luckily, a midday fighting lull allowed them to eat. Sarah’s “husband went to the garden and picked a mess of beans, though stray firing was going all the time, and bullets from sharpshooters or others whizzed about.” Picking beans amongst flying bullets made for a terrifying atmosphere. No matter, Sarah “baked a pan of shortcake and boiled a piece of ham,” and she, Joseph, Mary, and neighbors “had the first quiet meal since the contest began.” Cannonading shattered the short-lived reprieve; Sarah and Mary again waited, embracing, in a cellar. [11]

Citation: Tyson Brothers, “View of Gettysburg from Seminary Ridge,” July 1863, photograph, 2003.116.579, Adams County Historical Photographs, Adams County Historical Society, Gettysburg, PA.

Late that evening Sarah, still unable to rest, opened her diary and recorded this: “I have just finished washing a few pieces for my child, for we expect to be compelled to leave to-morrow.”[12] Doing laundry, like picking beans, on any other day is unremarkable and as routine as breathing. Having the forethought and energy to gather and heat water, scrub garments, wring them out, and hang them to dry in the midst of the bloodiest battle in American history is something else entirely. In short, it’s mothering that only war on the doorstep could demand.

That demand continued on July 3 when “heaven and earth” crashed together as Sarah clutched Mary in the dark of a cellar. Percussion from Pickett’s Charge reverberated in her body. While aware “that with every explosion” and every “scream of each shell” men were in pain and dying, she continued to exude composure.[13] Imagine the reassurances she offered for the little heart attached to her. A wee voice must have asked countless questions at every turn of the disruption. One most likely was, “Will we be okay, Momma?” Sarah probably paused and answered in the affirmative, outwardly collected though completely rattled by uncertainty.

Perhaps this line of her diary captures her best: “We do not know until tried what we are capable of.”[14] She was more than capable.

***

War was unkind to Mary and Sarah – and so many women tasked with tending to their children that July – but war could not undo them. Mothers, indeed.

Sarah Traphagen earned a Ph.D. in English from the University of Florida. Her areas of expertise are American literature, history, and Civil War medicine. She taught at the university level and in college preparatory schools before becoming a full-time home parent and instructor for the Learning Institute of New England College.

Endnotes:

[1] Cindy L. Small, Jennie Wade of Gettysburg: The Complete Story of the Only Civilian Killed During the Battle of Gettysburg. (Gettysburg Publishing, 2018), 24; 13.

[2] Small, 20.

[3] Small, 32.

[4] Small, 32; 39.

[5] Small, 39; 41.

[6] Small, 41-43.

[7] Small, 43.

[8] Sarah Kay Bierle, “My Favorite Historical Person: Sarah Broadhead,” Emerging Civil War, June 15, 2017, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2017/06/15/my-favorite-historical-person-sarah-broadhead/

[9] Sarah Broadhead, The Diary of a Lady of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, from June 15 to July 15, 1863. (Self-published, 1864), Cornell University Library Digital Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, New York, 10.

[10] Broadhead, 14; 15.

[11] Broadhead, 15.

[12] Broadhead, 16.

[13] Broadhead, 17.

[14] Broadhead, 22.