What a Civil War POW’s Envelope Can Tell Us

It is surprising how much information can be mined from a simple Civil War envelope.

On August 23, 1864, a Confederate prisoner of war penned a letter to his parents back home in Mississippi. The soldier wrote from the U.S. POW camp for Confederate officers at Johnson’s Island, located on Lake Erie near Sandusky, Ohio. The writer was Captain Matthew John Lucas (“MJL”) Hoye, a member of Company D (the “Newton Hornets”) of the 39th Mississippi Infantry Regiment.[1] Hoye is the great-grandfather of the author’s spouse, Martha Nase Donovan.

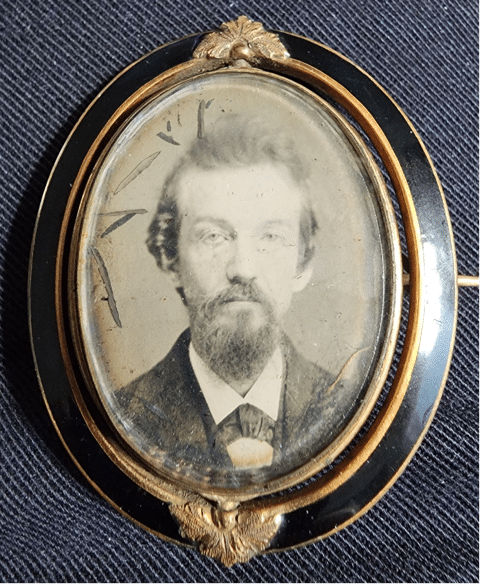

Matthew John Lucas Hoye (date unknown). Photograph provided by Euna Bunch, granddaughter of Karl Hoye, son of MJL Hoye.

MJL Hoye (January 7, 1842 – April 24, 1890) was born in Monroe County, Georgia.[2] In 1856 his family moved to Newton County, Mississippi. The 1860 census gave the then 18-year-old Hoye’s occupation as “Student.”[3]

Hoye enlisted in the Confederate army on April 19, 1862 as a “Third Lieutenant,” ultimately rising to the rank of Captain. But he was still a 1st Lieutenant when captured on July 9, 1863 along with the rest of the garrison of Port Hudson, Louisiana. [4] First sent by steamer to New Orleans, and later briefly to Governors Island in New York Harbor, Hoye arrived at Johnson’s Island on October 13. [5] Ten months later, Hoye wrote home.[6]

The one-page letter itself may be the subject of a future study. Here, however, we look only at the envelope, which upon careful examination reveals a surprising plethora of information.

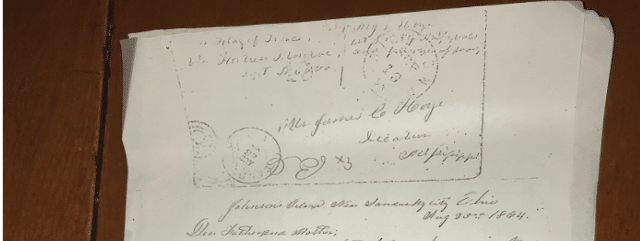

The envelope is addressed to Hoye’s father: “Mr. James C. Hoye, Decatur, Mississippi.” In the upper left side of the envelope is written, probably in MJL Hoye’s own hand: ‘[illegible but logically would be “Under”] Flag of Truce via Fortress Monroe …’ The remainder appears to be “Dept of Virginia,” the department in which the Fortress was located.[7] This all fits, as during the war Confederate POW mail was first sent to U.S.-occupied Fortress Monroe, Virginia to be sent under flag of truce across the lines to Richmond and then on to its ultimate destination within the Confederacy.[8]

The upper right side of the envelope clearly is in Hoye’s own hand. It reads: “MJL Hoye, 1st Lt 39th Miss vols, and prisoner of war.”

The 1st Lieutenant rank is curious. Hoye’s Confederate service records, starting in November 1863, refer to him as a Captain. By contrast, all the U.S. records the author has found identify him as a 1st Lieutenant, both as of the time of his capture and at the time of his ultimate release in 1865. Moreover, of course Hoye, whose handwriting is on the envelope, knew his correct rank (or at least what he thought it was). It thus is probable that he was promoted to captain while a POW without knowing it.[9]

The postmark in the upper right of the envelope is dated “Sept. 16” and reads “Richmond,” which makes chronological sense, as the postmark in the lower left reads “Sandusky O” (for Ohio) and is dated “Aug. 26 ‘64.” Thus, we know both when the letter started its journey, and that it safely made its way through Confederate lines three weeks later.

The envelope bears no stamps, either U.S. or Confederate, despite the fact that neither government permitted free mailings for POWs. Nor does there seem to be any space where stamps might once have been affixed, certainly not at the top of the envelope, where you would expect to find such. The explanation is this. POW correspondence was required to be enclosed in an unsealed envelope—unsealed so that the letter could be examined by a censor before it was put into transit—and sent together in another outer envelope with postage paid to the exchange point, in this case, Fortress Monroe. Thus, the outer envelope used by Hoye —which we do not have—is the one that would have needed U.S. postage. Once his letter within its inner envelope reached the Fortress, the outer envelope was discarded. Delivery from Fortress Monroe to the final destination required use of CSA postage or the cost of delivery was billed to the addressee.[10] Delivery to Richmond cost five Confederate cents, and then another five cents to reach its ultimate destination.[11]In Hoye’s case with this letter, we know that his father was asked to pay the ten cents postage due upon receipt in Mississippi, as reflected by the “10” faintly seen stamped immediately below the word “Monroe” in the upper left corner.[12] Thus, we learn that Hoye’s inner envelope – the one we have—was never intended to bear postage.

Most intriguingly, to the right of the Sandusky postmark, in the bottom center, is what appears to be meaningless scribble, immediately followed by what seems to be “x 3.” This all seems nonsensical, until one turns the envelope upside down. Only then does the writing reveal itself to be “Ex BC.” This is a genuine find. It means that somewhere along its journey the letter within the envelope was examined by a censor, someone with the initials “BC.”[13]

This led to a question. Could it be possible to identify “BC,” the man who personally handled and read Hoye’s letter before Hoye’s parents did? While finding the answer seemed unlikely, the search was worth the effort.

First, it was logical to assume that the censor, whoever he was, was stationed on Johnson’s Island itself. That POW site did use postal inspectors;[14] why expend resources carrying POW correspondence off the island only for some later clerk to determine that the letter contained contraband material or otherwise violated regulations? Thus, the censor must have come from among the Union personnel at the POW camp.

Research into the rolls of the soldiers stationed at Johnson’s Island suggested that Hoye’s censor might be Boyd Clendening, Barney Conley, or Benia Calvin, all members of “Hoffman’s Battalion” (128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry), the guard unit at Johnson’s Island, who each was serving there at the time Hoye’s letter was sent.[15] But how would it be possible to test this theory, let alone identify the correct man? This is where luck intervened.

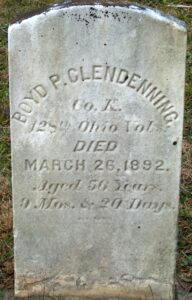

Learning that the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (a/k/a Virginia Tech) has a collection of Clendening Family correspondence, including a single letter from Boyd Clendening, the author was able to obtain a sample of Clendening’s handwriting. The goal was to compare the handwriting within that solitary letter exemplar to the initials “BC” found on the envelope, focusing especially upon the rather flamboyant manner of writing the capital letter “B.” The author struck gold. Based upon his review, the author is confident that Hoye’s letter censor “BC” in fact was Private Boyd Clendening of Company K, of the 128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Clendening (June 6, 1838 – March 26, 1892), originally from Berkeley County, (West) Virginia, moved to Ohio, where he enlisted in December 1863. Later, from his duty station on Johnson’s Island, Clendening would write to his family ‘attempting to convince the Clendenings to leave “that rebble country” in West Virginia’ and join him in Ohio. Clendening survived the war, moved to Pennsylvania, married and had at least six children.[16]

What did Clendening think about his mundane duty assignment as a censor? How did he feel about being tasked to examine the personal correspondence of a son—albeit a “rebble”—to his parents? We may never know his thoughts. But we do know what he did, and of his brief connection to my spouse’s ancestor, because in August 1864 that U.S. soldier left a small piece of evidence of his work on an envelope mailed by a Confederate POW.

This vignette is offered to illustrate that, with research, even a little piece of history can help provide at least a brief insight about not just one but two participants in America’s Civil War.

[1] A. J. Brown, History of Newton County from 1834 to 1894 (Clarion-Ledger Company, Jackson, MS 1894, republished by Melvin Tingle, Decatur, MS, printed by the Itawamba County Times, Inc., Fulton, MS 1964), p. 93; MJL Hoye Confederate Service Record, obtained from Fold3byAncestry.com.

[2] Mae Helen Clark, The Hoye Family of Newton County, Mississippi, pp. 9, 11. The Clark article is among the documents provided the author by Matthew R. Lawrence, Esq., of Valdosta, Georgia, a Hoye family descendant.

[3] The Census information was contained in an August 20, 2023 email to the author from R. Hugh Simmons, of the Fort Delaware Society. Mr. Hughes provided information regarding both Hoye’s life and military service, including his POW experience while at Fort Delaware in 1865.

[4] MJL Hoye Confederate Service Record.

[5] MJL Hoye Confederate Service Record.

[6] This does not mean that this letter was Hoye’s first, or only, letter home. However, it is the only correspondence known to be in Hoye family possession. Copies of both the envelope and letter itself were provided by Victor C. Hoye, Jr., a Hoye family descendant.

[7] “Fort Monroe During the Civil War,” Encyclopedia Virginia, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/fort-monroe-during-the-civil-war/#:~:text=The%20fort%20also%20headquartered%20the,fated%20Peninsula%20Campaign%20of%201862.

[8] David R. Bush, I Fear I Shall Never Leave This Island: Life in a Civil War Prison (University of Florida Press, Gainesville, FL, 2011), p. 18.

[9] In this regard, J. C. McElroy, the original Captain of Company D, resigned due to disability prior to the siege of Port Hudson. Ref: Memoirs of Mississippi Vol. I & Mrs. A. L. Myers of Newton, found athttps://www.findagrave.com/memorial/34875304/jackson-carrol-mcelroy.

Perhaps Hoye was serving as company commander without the formal appointment to the appropriate rank until some point after his capture, but at a time when his exchange and return to active service were still thought probable.

[10] Union Handling of the Mail During the American Civil War, “Flag-of-Truce Prisoner-of-War (POW) Mail,” https://www.rfrajola.com/Knowles1/Knowles1.pdf.

[11] David R. Bush, I Fear I Shall Never Leave This Island: Life in a Civil War Prison (University of Florida Press, Gainesville, FL, 2011), p. 18.

[12] Union Handling of the Mail During the American Civil War (discussing the use of the stamped postage due number system).

[13] Bush, p. 19 (referring to the notation on an outgoing letter’s envelope that it had been examined by a censor).

[14] Bush, p. 19.

[15] National Park Service, Union Ohio Volunteers, 128th Regiment, Ohio Infantry, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UOH0128RI and Search for Soldiers, 128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-soldiers.htm#q=%22128th%20Regiment,%20Ohio%20Infantry%22. This site identifies the 128th Ohio’s soldiers, including when each enlisted. https://civilwardata.com/active/hdsquery.dll?Muster?a=1754&b=U&c=&d=1&e=169&f=20.

The battalion was named for William Hoffman, Commissary General of Prisoners. Roger Pickenpaugh, Johnson’s Island: A Prison for Confederate Officers (The Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2016), pp. 2, 7.

[16] Box 1, Folder 1, Clendening Family Letters, Ms1991-067, Special Collections and University Archives, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va.

This is the most fascinating piece I have read in a long time. Thank you!

Mark, thank you kindly.

This fascinating piece was interesting from start to finish, as evidence of solid detective work, compelling story-telling in fleshing out the Civil War POW Experience, and…

For me, personally, I resumed my Civil War interest about twenty years ago while conducting Family History research and learning that an ancestor – Thomas Clendenin – a private in the 12th Iowa Infantry, Company H, was captured with most of his regiment at Shiloh’s Hornet’s Nest in April 1862. The “Old Twelfth” was confined in a number of prisons across the South, including the Parole Camp at Annapolis Maryland, before the final exchange of prisoners captured at Shiloh was completed late 1862/ early 1863.

The unbelievable information found in Kevin Donovan’s article: Boyd Clendening. When the “Glendining” family arrived in Philadelphia about 1690, two brothers [spelling their name Clendenin] settled in Pennsylvania; the third brother went south, spelt his name Clendening… and contact was lost. It was assumed “the Clendenings stayed south” while the Clendenins moved steadily westward, settling in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa… and some of the family adopted Clendenen, and others Clendennen for spelling of the last name. To find a Clendening living in Ohio at the time of the Civil War opens up another potential branch of cousins, previously unknown. “Six degrees of separation…?”

Mike, thank you. The Virginia Tech archives have letters from other family members that might be of interest to you. Depending on the amount of material, VaTech will download such and email you a temporary link, obviating the need for a personal visit.

Great detective work, Kevin. It is amazing what you discovered with so little. I wonder if Hoye’s rank of captain was a brevet or he was called such because he may have been doing the job of a captain? Really enjoyed the article. I have visited Johnson’s Island a number of times and Sandusky, Ohio has a museum about the prison. The site underwent an archeological dig a few years ago by a professor from Tiffin, Ohio who found a number of artifacts from the prison. Great article.

Great article and great detective work Kevin. Wondered if your wife’s ancestor was a captain by brevet or just referred to himself as captain because he was acting in that capacity? I have been to Johnson’s Island and cemetery a number of times. A few years ago, a professor from Heidelburg College in Tiffin, Ohio conducted an archeological dig at the prison site and recovered a number of artifacts. I think most of them are catalogued at a Johnson’s Island Prison museum in Sandusky. It is also interesting how one bit of research helps make further discoveries such as in Mike Maxwell’s case. Great Job.

Brian, thank you. I would like to visit Johnson’s Island someday.

You raise an interesting point that maybe others can address. I have never seen any evidence that the Confederates used the brevet system, which seems odd, as the CSA army essentially adopted old US army procedures. Also, the use of the “Third Lieutenant” baffles me a bit. My research has found some dispute on whether “Third Lieutenant” was an actual rank or simply referred to the job duties of a junior Lieutenant. It appears, however, to have been an actual rank, in at least the Provisional Confederate States of America Army (as opposed to the Regular Confederate Army).

Bully research fascinating article.

Henry, thank you. It has been a fun and rewarding project to research my spouse’s Civil War ancestor.

Matthew Hoye as a “Third Lieutenant” – what is the history of such rank? Was it only a product of the Civil War? Did it exist in the Federal army as well? in all my reading I had never heard of this, but now twice in one year have read of Confederates being “Third Lieutenant.” Anyone?

George, here is what I have found (excerpted from my work on a bio of MJL Hoye):

“Third Lieutenant” is not a rank known in present military jargon. Moreover, my research has found some dispute on whether “Third Lieutenant” was an actual rank or simply referred to the job duties of a junior Lieutenant. It appears, however, to have been an actual rank, in at least the Provisional Confederate States of America Army (as opposed to the Regular Confederate Army). See the discussion at Civil War Talk, a forum about the American Civil War, https://civilwartalk.com/threads/what-are-the-duties-of-a-third-lieutenant.120581/; compare Richard P. Weinert, The Confederate Regular Army, pp. 128-129, Appendix B (White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., Shippensburg, PA 1991) (no listing of Third Lieutenant, but reference to “Cadet” rank in the place at which Third Lieutenant would be expected to appear).

For an explanation of the “Provisional” Army forces, see The Confederate Regular Army, p. 4 and Rembert W. Patrick, Editor, The Opinions of the Confederate Attorneys General, pp. 6-8 (“Volunteer and Provisional Forces”) (William S. Hein & Co., Inc., Buffalo, NY, 2005).

The rank of Third Lieutenant and its role (file closer) are discussed in Hardee’s Tactics. W. J. Hardee, Rifle & Light Infantry Tactics, Vol. I, p. 7, Section 18 (J. B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia, PA 1861). While U.S. Army Regulations of the era made no reference to the rank of Third Lieutenant, the rank of “Cadet” was listed, placed below the rank of Second Lieutenant and above Sergeant-Major. Revised Regulations for the Army of the United States: 1861, p. 9, Article II, Section 4 (Rank and Command) (National Historical Society, Harrisburg, PA 1980). Thus, it may be that Third Lieutenant was used instead of the commissioned rank of Cadet, a rank that did exist in the Regular Confederate Army. See An Act to increase the Military establishment of the Confederate States, and to amend the “Act for the establishment and organization of the Army of the Confederate States of America,” Chapter XX, Section 8, Approved May 16, 1861, https://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/19conf/19conf.html.

It was an old rank that did not survive beyond the US Civil War. Where did it go? I do not know. But, it existed in the US Army for some amount of time. Sam Houston, future governor of Texas, was a 3rd Lieutenant in the War of 1812. He was promoted from ensign to 3rd Lieutenant. The link will not post, but you can look at the entry for Sam Houston on Texas State Historical Assoc. online.

Tom

Interesting. Thank you. I’ll incorporate your information.

By the time he sent the letter, MJL Hoyle would have been “treated” to a Lake Erie winter on Johnson’s Island. If the winter of 1864 was like the one we in CLE experienced this year, he had to be miserable and likely, commented about the harsh conditions ( either in this letter, or an earlier one).

MJL Hoye did not comment on the winter weather in the one letter we have (sent in August 1864), but Henry Kyd Douglas, of Stonewall Jackson’s staff, wrote of his time at Johnson’s Island: “[T]he 42 [degree] of Latitude, North, is hardly the place Southerners would select as a winter resort. Johnson’s Island, however, was just the place to convert visitors to the theological belief of the Norwegian that Hell has torments of cold instead of heat.”

Douglas knew of what he spoke. Several times during the winter of 1863-1864 the temperature dropped below zero, with 39° below zero the lowest temperature recorded. The situation was aggravated because nighttime stove fires were forbidden the POWs (due to the fear of fire breaking out in the night).

It is difficult to imagine the conditions that you describe. This year 95% of Lake Erie froze/ice covered. With the weather you described, that might have occurred in 1864. Johnson Island would be exposed to a long expanse of ice with winds from the north and west. Brrrr.

True. The cold was so bad one of the POWs wrote to the CSA Secretary of War, asking him to send US dollars to the prison so that the POWs could purchase warm clothing. Nothing came of the plea. But, on the other hand, the frozen lake was used to facilitate prison escapes to the mainland. POWs walked across the ice.