A Few Notes on Grant’s Last Battle

Part two of two comes from my “author’s note” in Grant’s Last Battle: The Story Behind The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant.

As kids, my brother and I had a poster of the presidents on the closet door in our bedroom. My brother picked Lincoln as his favorite. I picked Ulysses S. Grant. I liked how grand the name sounded, and I knew he smoked cigars, which also seemed grand. That was about the extent of my knowledge.

My first real introduction to Grant came as it did for Robert E. Lee: in the Wilderness of central Virginia. There, I learned about the “dust-covered man” who had vowed that there would be no turning back. I have since spent a great deal of time on that battlefield, as well as the ones at Spotsylvania and North Anna, sharing stories of Grant’s time in the east. I have also visited the sites of his major battles out west. I have come to admire him a great deal.

I often liken Grant to another of my favorite characters from the war, Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. Both were men of deep resolve. I have seen how their resolve played out dramatically—and in dramatically different ways—on the battlefields around Fredericksburg, Virginia. Grant’s final 15 months likewise demonstrate his resolve, and in an especially striking way. That’s what has always drawn me to the story.

I’ve also been drawn to that story as a writer, particularly one who has studied and practiced memoir. Memoir is a particularly tricky form of nonfiction, not reliant on facts but on larger truth. “Truth derives from facts but is not dependent on them,” says historian Joan Waugh. “It is based in the facts but ultimately not answerable to them. Today, professional historians call truth ‘Interpretation.’”

Grant was especially meticulous about his fact-checking, but what he writes and what he doesn’t, and what conclusions he draws from those facts, are all products of memoir, not of history writing. “By deciding to give his work the full title, Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant,” says historian Charles Bracelen Flood, “he did himself a great favor. He could write about the things he wished to put before the reader, and omit those things he did not. At one stroke, he relieved himself of the obligation to include everything he might know about a battle or a person, while reserving the right to dwell on a smaller matter or fleeting perception.”

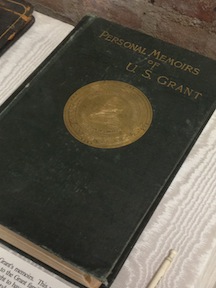

I own a first edition of the Memoirs, but I have another connection to Grant’s story, as well. When Grant was general in chief of the army during Andrew Johnson’s administration, he and Julia lived in a Washington, D.C., townhouse at 205 I Street NW near the capitol (Sherman lived in #203). Julia Grant referred to it as “this lovely house, this magnificent home.” Upon the failure of Grant & Ward in 1884, the Grants sold all of their D.C. properties, and by 1965, the entire row of townhouses was demolished to make way for Interstate 395. The wooden doors from the Grants’ townhouse found their way, years later, to Stevenson Ridge in Spotsylvania, Virginia—my wife’s family’s property. Every day, I walk through a small piece of the collateral damage from Grant’s final battle.

The story of Grant’s last battle has been told by others, and I strongly encourage you to read their accounts. My take, in introducing readers to these events, is slightly more personal, keeping in the spirit of both history and memoir. By sharing it in such a way, I hope to help them connect with Grant’s story in the kind of personal way I have connected with it, too.

Two excellent posts. I am looking forward to reading your book.

I’ll finish reading this post if it takes all summer….

I look forward to your book and hope to pick it up at the Symposium! And I enjoy the part of the article about the doors that you walk through having been part of Grant’s former residence and how much that means to you. I really started writing and researching the Civil War in a focused way when I wrote an article for my local Roundtable’s newsletter on a soldier for which no information was known, and lo and behold, he’s one of Grant’s second cousins. I hadn’t known of Grant’s connection to my home, and I was astonished to find it. It’s these unique and less-known subjects related to these major individuals in American history that just make them all the more interesting.