Baseball In The Blue And Gray (Part 2)

Emerging Civil War welcomes guest author Michael Aubrecht for Part 2 of his article. (You can find Part 1 here.)

It has been disputed for decades whether Union General Abner Doubleday was in fact the “father of the modern game.” Many baseball historians still reject the notion that Doubleday designed the first baseball diamond and drew up the modern rules. Nothing in his personal writings corroborates this story, which was originally put forward by an elderly Civil War veteran, Abner Graves, who served under him. Still, the City of Cooperstown, New York dedicated Doubleday Field in 1920 as the “official” birthplace of organized baseball. Later, Cooperstown became the home of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Doubleday was an 1842 graduate of West Point (graduating with A.P. Stewart, D.H. Hill, Earl Van Dorn and James Longstreet) and served in both the Mexican and Seminole Wars. In 1861, he was stationed at the garrison in Charleston harbor. It is said that it was Doubleday, then an artillery officer, who aimed the first Fort Sumter guns in response to the Confederate bombardment that initiated the war. Later he served in the Shenandoah region as a brigadier of volunteers and was assigned to a brigade of Irwin McDowell’s corps during the campaign of Second Manassas. Doubleday commanded a division of the 1st Corps at Sharpsburg and Fredericksburg, as well as at Gettysburg, where he assumed command of the 1st Corps after the fall of General John E. Reynolds on the first day’s fighting. His corps helped to repel Pickett’s Charge on the third day of the battle at Gettysburg.

Strangely, General Doubleday’s outstanding military service is often forgotten, yet his controversial baseball legacy lives on. A report published in 1908 by the Spalding Commission (appointed to research the origin of baseball) credited Union General Abner Doubleday as being the “father of the modern game.” It stated, “Baseball was invented in 1839 at Cooperstown by Abner Doubleday—afterward General Doubleday, a hero of the battle of Gettysburg—and the foundation of this invention was an American children’s game called ‘One Old Cat.’”

Since then, Alexander J. Cartwright, Jr. has been designated as the game’s principal founder. According to sources at the Fort Ward Museum, “In 1842, at the age of 22, Cartwright was among a group of men from New York City’s financial district who gathered at a vacant lot at 27th Street and 4th Avenue in Manhattan to play ‘baseball.’ In 1845, they organized themselves into the Knickerbockers Base Ball Club, restricting the membership to 40 males and assessed annual dues of five dollars. The following year, Cartwright devised new rules and regulations, instituting foul lines, nine players to a team, nine innings to a game and set up a square infield, known as the ‘diamond’ with 90-foot baselines to a side, bases in each corner. He also drew up guidelines for punctuality, designated the use of an umpire, determined that three strikes constituted an out, and that there would be three outs per side each inning.”

Cartwright left the New York area in 1849 to travel. He was drawn by the Gold Rush and stories of adventures in the West. Along the way, he taught the game to Native Americans and mountain men he encountered, spreading interest in the fledgling sport west of the Mississippi. Cartwright died in Hawaii in July of 1892. However, for decades to come, it was Doubleday who remained in the hearts and minds of enthusiasts everywhere as baseball’s father.

To his credit, the general is said to have always demurred on assertions by others that he was the founder of the national game. Yet the legend persisted decades after his death. Regardless of falsely being credited as the sole “inventor” of the modern version, Doubleday was an evident student and fan of the game. Some historians believe that he helped to organize contests in camp, possibly prior to the Battle of Chancellorsville. At the time of the engagement in early May, some 150+ years ago, Doubleday was in command of the 3rd Division, 1st Corps. According to sources at the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Doubleday was in the area from the summer of 1862 through the Battle of Fredericksburg in December, and the Battle of Chancellorsville in May of 1863.

It has been determined that baseball was played “extensively” by Union soldiers in nearby Stafford County during that time, but there is no known documentation of Doubleday’s hand in games thereabouts. Perhaps a more realistic accolade would credit him with the promotion of the exercise as opposed to the invention of it. Many of these contests were attended by thousands of spectators and often made front-page news equal to the war reports from the field. Ultimately, the Civil War helped fuel a boom in the popularity of baseball, evidenced by the fact that a ball club called the Washington Nationals was born in 1860—145 years before a Major League Baseball team in Washington, D.C. was given the same name.

In 1861, at the start of the war, an amateur team made up of members of the 71st New York Regiment defeated the Washington Nationals baseball club by a score of 41–13. When the 71st New York later returned to man the defenses of the capital in 1862, the teams played a rematch, which the Nationals won 28–13. Unfortunately, the victory came in part because some of the 71st Regiment’s best athletes had been killed at Bull Run only weeks after their first game. One of the largest attendances for a sporting event in the 19th century occurred on Christmas in 1862 when the 165th New York Volunteer Regiment (Zouaves) played at Hilton Head, South Carolina. The Zouaves’ opponent was a team composed of men selected from other Union regiments. Interestingly, A.G. Mills, who would later become the president of the National League, participated in the game.

According to George B. Kirsch’s 2003 book Baseball in Blue & Gray, John G.B. Adams of the 19th Massachusetts Regiment recounted that “base ball fever broke out” at a Falmouth encampment in early 1863 with both enlisted men and officers playing. The prize was “sixty dollars a side,” meaning the winning team paid the losers that sum. “It was a grand time, and all agreed it was nicer to play base than minie ball.” Adams reported that around the same time, several Union soldiers watched Confederate soldiers play baseball across the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg. Nicholas E. Young of the 27th New York Regiment, who later became a president of baseball’s National League, played the game at White Oak Church in Stafford County. Union soldier Mason Whiting Tyler wrote home that baseball was “all the rage now in the Army of the Potomac.”

According to George B. Kirsch’s 2003 book Baseball in Blue & Gray, John G.B. Adams of the 19th Massachusetts Regiment recounted that “base ball fever broke out” at a Falmouth encampment in early 1863 with both enlisted men and officers playing. The prize was “sixty dollars a side,” meaning the winning team paid the losers that sum. “It was a grand time, and all agreed it was nicer to play base than minie ball.” Adams reported that around the same time, several Union soldiers watched Confederate soldiers play baseball across the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg. Nicholas E. Young of the 27th New York Regiment, who later became a president of baseball’s National League, played the game at White Oak Church in Stafford County. Union soldier Mason Whiting Tyler wrote home that baseball was “all the rage now in the Army of the Potomac.”

George T. Stevens of the New York Volunteers said that in Falmouth, “there were many excellent players in the different regiments, and it was common for one regiment or brigade to challenge another regiment or brigade. These matches were followed by great crowds of soldiers with intense interest.”

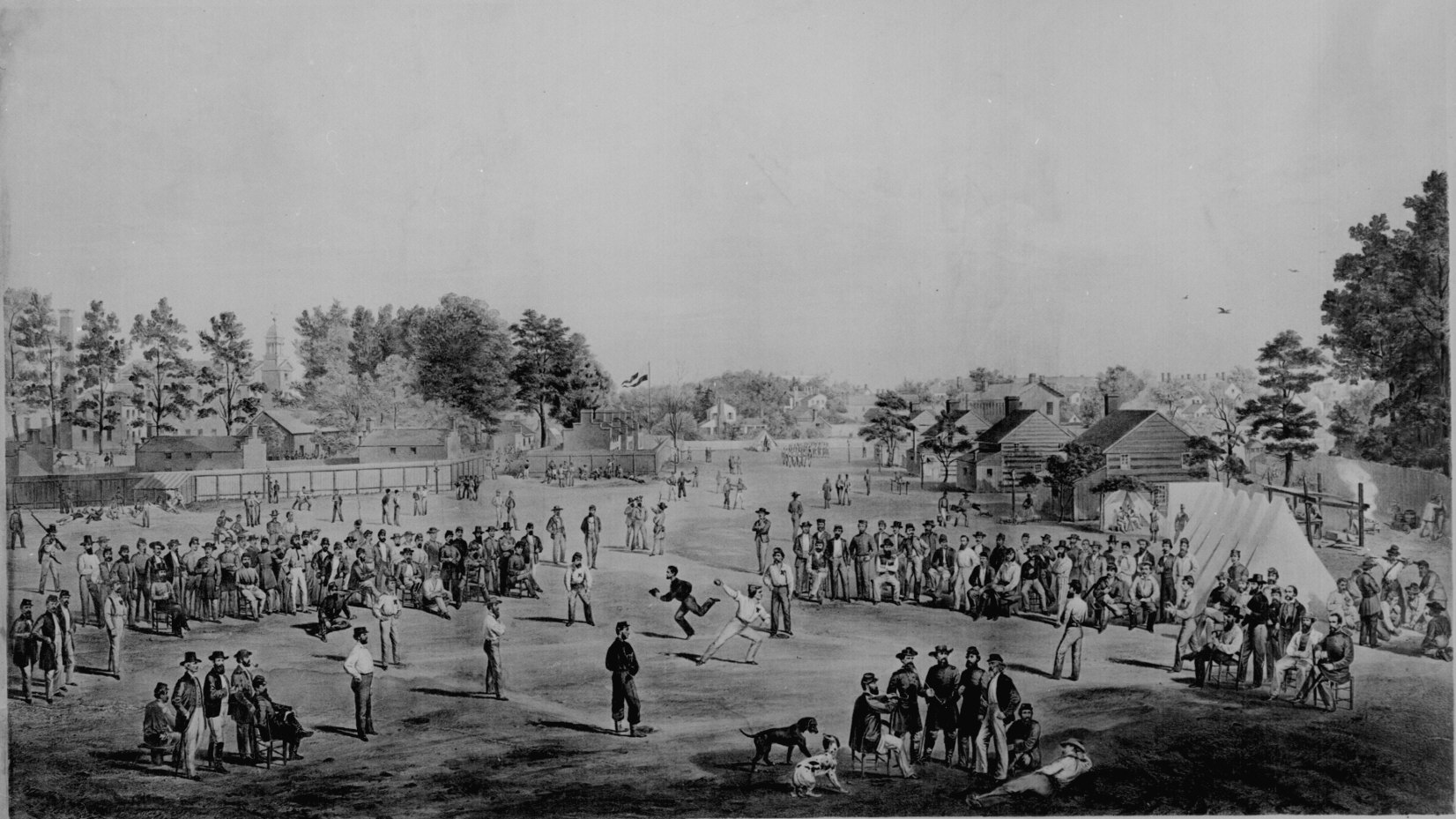

Day-to-day life was tough, but prisoners had a large yard with plenty of room to move about. One of the favorite activities before the prison became overcrowded was baseball. So prevalent was the game at Salisbury that it was captured in an 1863 print. This illustration romantically represents one of the earliest depictions of the game and recalls the days before overcrowding greatly diminished the camp’s living conditions. The illustration was penned by Otto Boetticher, a commercial artist from New York City, who had enlisted in the 68th New York Volunteers in 1861 at the age of 45. He was captured in 1862 and was sent to the prison camp at Salisbury. During his time there he produced a drawing that depicted the game in a more pastoral than prison-like setting.

A field reporter named W.C. Bates mentioned the presence of baseball at Salisbury in his Stars and Stripes publication. He added that, “we have no official report of the match-game of baseball played in Salisbury between the New Orleans and Tuscaloosa boys, resulting in the triumph of the latter; the cells of the Parish Prison were unfavorable to the development of the skill of the ‘New Orleans nine.’ Prisoner Gray mentions that baseball was played nearly every day the weather permitted. Claims have been made that these were the first baseball games played in the South.”

“Prisoner Gray” was actually Dr. Charles Carroll Gray, who indicated in his diary on July 4th that the day was “celebrated with music, reading of the Declaration of Independence, sack and foot races in the afternoon, and also a baseball game.” Gray fondly recalled that baseball was played almost every day. Sgt. William J. Crossley of Company C, 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, described in his memoirs at Salisbury prison that “the great game of baseball generated as much enjoyment to the Rebs as the Yanks, for they came in hundreds to see the sport.”

More than a decade after the Civil War ended, the National League was developed. Coincidentally, it was the same year that General George Armstrong Custer was killed, along with 264 Union Cavalry troopers, after engaging Indian warriors at Little Bighorn. The year was 1876, and the National League of Professional Baseball was formed with an eight-team circuit consisting of the Boston Red Stockings, Chicago White Stockings, Cincinnati Red Legs, Hartford Dark Blues, Louisville Grays, Philadelphia Athletics, Brooklyn Mutuals and St. Louis Browns. It has been reported that many members of the U.S. Cavalry, most of them veterans of the Civil War, engaged in baseball games to pass the time while protecting the western territories. Some of them returned home to witness the likes of Ross Barnes of Chicago hit the first National League home run, which was an inside the park variation. A Cincinnati pitcher named William “Cherokee” Fisher served up that historic pitch.

Regardless of its location, whether in prison camps or in the field, baseball provided an escape from the harsh realities of war and ultimately improved the morale of troops who were obviously homesick, scared, and in some cases, traumatized by the horrors they had witnessed on the battlefield. After the war ended, many men from both sides returned home to share the game that they had learned near the battlefield. Eventually organized baseball grew in popularity abroad and helped bring together a country that had been torn apart for so many years.

Regardless of its location, whether in prison camps or in the field, baseball provided an escape from the harsh realities of war and ultimately improved the morale of troops who were obviously homesick, scared, and in some cases, traumatized by the horrors they had witnessed on the battlefield. After the war ended, many men from both sides returned home to share the game that they had learned near the battlefield. Eventually organized baseball grew in popularity abroad and helped bring together a country that had been torn apart for so many years.

Today, over a century later, baseball is still a popular American institution and remains a testament to both “Billy Yank” and “Johnny Reb” who laid down their muskets to pick up a ball and help to establish a National Pastime. Perhaps it was Walt Whitman, one of America’s most prolific poets, who correctly predicted how a game played with a stick would grow into one of our country’s most prized possessions. He wrote: “I see great things in baseball. It’s our game—the American game. It will take our people out-of-doors, fill them with oxygen, and give them a larger physical stoicism. Tend to relieve us from being a nervous, dyspeptic set. Repair these losses and be a blessing to us.”

Michael Aubrecht is an author, as well as a Civil War Historian. He has written several books including The Civil War in Spotsylvania and Historic Churches of Fredericksburg. Michael was also a contributing writer for Baseball-Almanac from 2000-2006. He lives in historic Fredericksburg. Visit his blog online at https://maubrecht.wordpress.com/.

SOURCES:

George B. Kirsch, Baseball in Blue & Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003)

George B. Kirsch, “Bats, Balls and Bullets: Baseball and the Civil War,” Civil War Times Illustrated, Vol. XXXVI, No. 2, (Harrisburg, PA, May 1998)

Harvey Frommer, Primitive Baseball: The First Quarter Century of the National Pastime (Atheneum; 1st edition, April 1998)

J.G. Adams, Reminiscences of the 19th Massachusetts Regiment (Boston: Wright and Porter, 1899).

Michael A. Aubrecht, Baseball and the Blue and Gray (Baseball-Almanac: Pinstripe Press, 2004)

Patricia Millen, From Pastime to Passion: Baseball and the Civil War (Heritage Books, January 2001).

Doubleday had absolutely nothing to do with the origins of baseball. In 1839, he was a plebe at West Point and plebes did not have time to go home and invent games!

There is an excellent discussion of the myth of Abner Doubleday at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doubleday_myth

It points out there is exactly one mention of baseball in his papers: in 1871 he requested some equipment!

Thank you for reinforcing my findings above. It is amazing how long that myth has lasted. Thankfully Alexander Cartwright is being validated by most historians today.

I agree completely with Mr. Huddleston and appreciate he took my bait with his correction re: Doubleday viz. baseball. The whole business was invented by local realtor in the Cooperstown area in the 1930s. I suppose there were economic reasons for that fiction to be accepted by baseball, as well. In the 1930s there was no Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) to immediately knockdown the Cooperstown-Doubleday claim. But Cooperstown IS a pleasant place for a Hall of Fame, one would agree.

Thank you for your comments too. As I wrote above Alexander Cartwright is the rightful owner of the title of baseball’s founder.

More recent scholarship suggests that while Cartwright had more to do with baseball than Doubleday (a not hard bar to clear), he was nowhere near as central a figure in early baseball as some (notably his grandson) have claimed.