Disease: A Tale of Two Regiments (Part 2)

We are happy to welcome back Jim Sundman for part 2 of his Disease series.

In late October 1862 my ancestor Garrett Bush deserted his regiment while it was encamped on Maryland Heights across from Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Bush was one of dozens of soldiers in the 13th to desert that fall, and in order to better understand why he and others left the unit I examined the conditions the men were facing as a newly-formed regiment. Certainly home sickness, hunger, exposure to the elements, and low morale were key factors in desertion, but one important contributor could have been to avoid death itself. Similar to a soldier running in battle to escape what he believes will be his untimely death, these men could have ran to avoid sickness and disease that was ravaging their brigade during that period.

In the first part of this article I introduced Bush’s regiment – the 13th New Jersey – and another new regiment – the 107th New York – that were formed during the summer of 1862. These units were brigaded together, marched into the Battle of Antietam together, and then encamped together on Maryland Heights. Due to the worsening weather, inadequate shelter, poor food and water, and a piece of ground not favorable as camp site, the men became very sick. But the deaths in both regiments were far different, impacting the New Yorkers much more than the Jerseymen.

Though both regiments suffered terribly, the death toll in the 107th beginning with Corporal Joseph Couse on October 1st would far surpass the death toll in the 13th that began three weeks later with Private Martin V.B. Demarest. In fact, by the time the 13th’s Demarest died, the 107th saw more than a dozen deaths due to sickness and disease. But it would not end there. In October 1862 alone, 22 New Yorkers died from disease compared to just three Jerseymen. Describing the conditions, the 107th’s Captain Newton Colby wrote to his father back in Elmira:

“Our men are very unhealthy and several have died here – I have lost none by sickness yet – but we have not got over 250 men fit for duty – out of the 1000 we brot here! We have a funeral nearly every day – My men lie on the ground without shelter (except bush tents which are no protection against rain) and many of them without overcoats or blankets – and it is not strange they sicken.”

Sergeant Russell Tuttle, also of the 107th New York, noted his concern of the conditions in his journal: “In addition to all my cares, I have to take care of a friend who lies in our tent very, very ill. It is Almen W. Burrill. I fear that he cannot live; and here he lies, his only bed, a blanket with a little straw beneath it. We do the best we can for him, but what can we do here?” Burrill (spelled Burrell in the regiment’s roster) was sent to a hospital in Philadelphia where he died in early January.

The suffering of the 107th, however, did not go unnoticed by the Jerseymen. The 13th’s commanding officer Colonel Ezra Carman noted in his diary in mid-October: “So far we have lost none by disease in which respect we have been more highly favored than the 107th New York which have lost quite 15 men since camping here and continue to lose daily.”

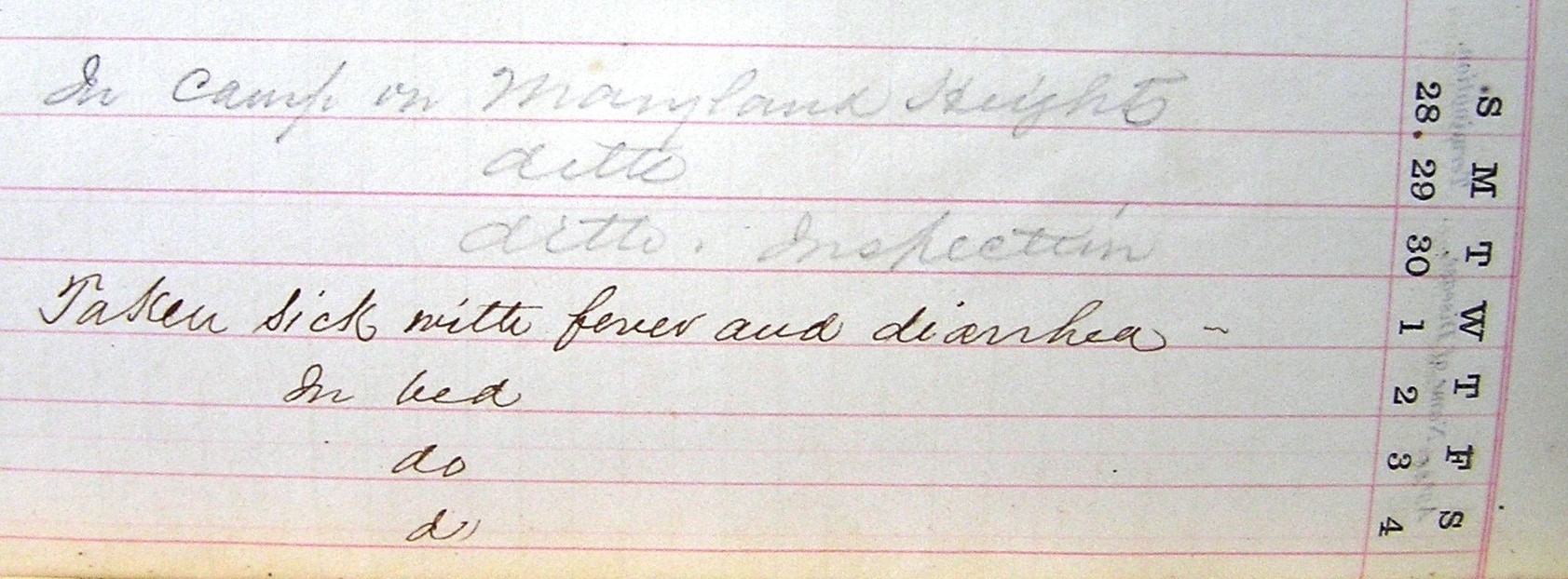

Though numerous diseases and sicknesses were prevalent throughout the Civil War, including dysentery, tuberculosis, measles, malaria, and pneumonia, most of the men who died on Maryland Heights during the fall of 1862 died from typhoid fever. Typhoid is an intestinal disorder caused by the salmonella typhibacteria, and is usually caused by ingesting contaminated food and water. Once ingested into the body, the salmonella bacteria multiply in the blood stream initially causing severe headache and fever, followed by joint pain, sweating, sore throat, and coughing. A general loss of appetite, reddish spots, enlarged spleen, and general listlessness are also symptomatic.

During a second phase of the disease, the bacteria are absorbed into the digestive tract, liver, and bone marrow, which causes violent diarrhea as it enters the small intestine. High fever will continue, and the patient can experience a slowing heartbeat and weakened pulse. With no antibiotics in the 1860s to combat the disease, the death rate of typhoid patients was extremely high. “On Maryland Heights” the 107th’s Captain Gustavus Brigham later wrote, “we listened to the daily sad dirge of the drum which answered to the havoc created in our ranks by typhoid fever.”

At the time it was unclear how typhoid spread, but the conditions on Maryland Heights were similar to that of Camp Thomas in 1898, a U.S. Army training ground established on the old Chickamauga battlefield in Georgia. That year, hundreds of men died of typhoid fever at the camp. The Typhoid Commission, established by the U.S. Surgeon General’s office to study the disease and its proliferation in U.S. Army camps discovered that the ground of Camp Thomas was very rocky and made digging latrines extremely difficult. Even latrines that could be dug to any sufficient depth were almost useless as the clay soil in that area has almost no absorption qualities. Therefore, with no waste management in place, the camp was one gigantic privy. “I have never seen so large an area of fecal-stained soil as that which we looked upon and walked over in Chickamauga Park in 1898,” said Dr. Victor Vaughan, one of the Commissioners.

Maryland Heights has the same characteristics. Bedrock lies just below the surface on the Heights, and digging latrines deep enough was nearly impossible. The 1861 Army regulations dictated the size, design, and placement of regimental camps, even for the specific positioning of latrines, or sinks as they were called. However, with the steep slopes on the Heights and with thousands of troops occupying a smaller than normal area, “Maryland Heights met none of these criteria” noted one historian. Normally, latrines were to be placed 150 paces (about 450 feet) to the rear of the regimental company tents. However, archaeological surveys of the campgrounds on Maryland Heights showed no evidence of latrines. Whatever was dug there overflowed with the heavy rains that fall, contaminating the campground.

But if both regiments were equally exposed, why was the death rate so much higher among the New Yorkers? There are several reasons. First, the 107th New York was established in a predominantly rural area of the state, and as such, soldiers in that regiment had little exposure to diseases that flourished in the cities of America. An estimated two-thirds of the 107th’s men were farmers or farm laborers before enlisting. In addition, there were also a handful of lumbermen, sawyers, and millers in the regiment, indicating that the majority of these men lived a rural lifestyle. For many it would be the first time in their lives living day to day among hundreds of other men.

The 13th New Jersey on the other hand had an unusually small number of deaths due to sickness and disease during the war. Most of the men in this regiment came from urban areas of northeast New Jersey where they lived and worked in often crowded and unsanitary conditions. In fact, the City of Newark itself (where 45 percent of the 13th’s men lived before enlisting) was dubbed the unhealthiest city in America in the 19th century. As Newark rapidly grew during the decades leading up to the Civil War, its commitment to public health severely lagged. Diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and dysentery, all took victims in the city. But it also had one positive benefit: it exposed many of the 13th’s soldiers to the diseases that were not only uncommon in rural areas of the country, but would flourish in Civil War campgrounds. Therefore, though hundreds of men were sickened in both regiments, a shoemaker from Newark, New Jersey had a much higher tolerance to disease than a farmer from Schuyler County, New York.

Another possible reason for the disparity in disease-related deaths is the number of foreign-born soldiers who served in the 107th and 13th New Jersey. European-born immigrants may have been exposed to many of the diseases faced by soldiers during the Civil War, especially on crowded ships coming to the United States. In the 13th New Jersey about 29 percent of the soldiers were foreign born, the majority of whom (over 90 percent) were born in Europe. On the other hand, the percentage of foreign-born soldiers in the 107th was probably less than 10 percent.

Disease-related deaths were more prevalent in younger soldiers too. While the average age of a soldier in the 107th New York was 26 years, the average age of those who succumbed to disease in this unit was 24 years. To look at it another way, 24 percent of the New Yorkers were under the age of 20, but those under 20 accounted for 35 percent of the disease-related deaths. While the average age of a soldier in the 13th New Jersey was also 26 years, this regiment had a slightly smaller proportion (21 percent) of their rolls under 20 than the New Yorkers.

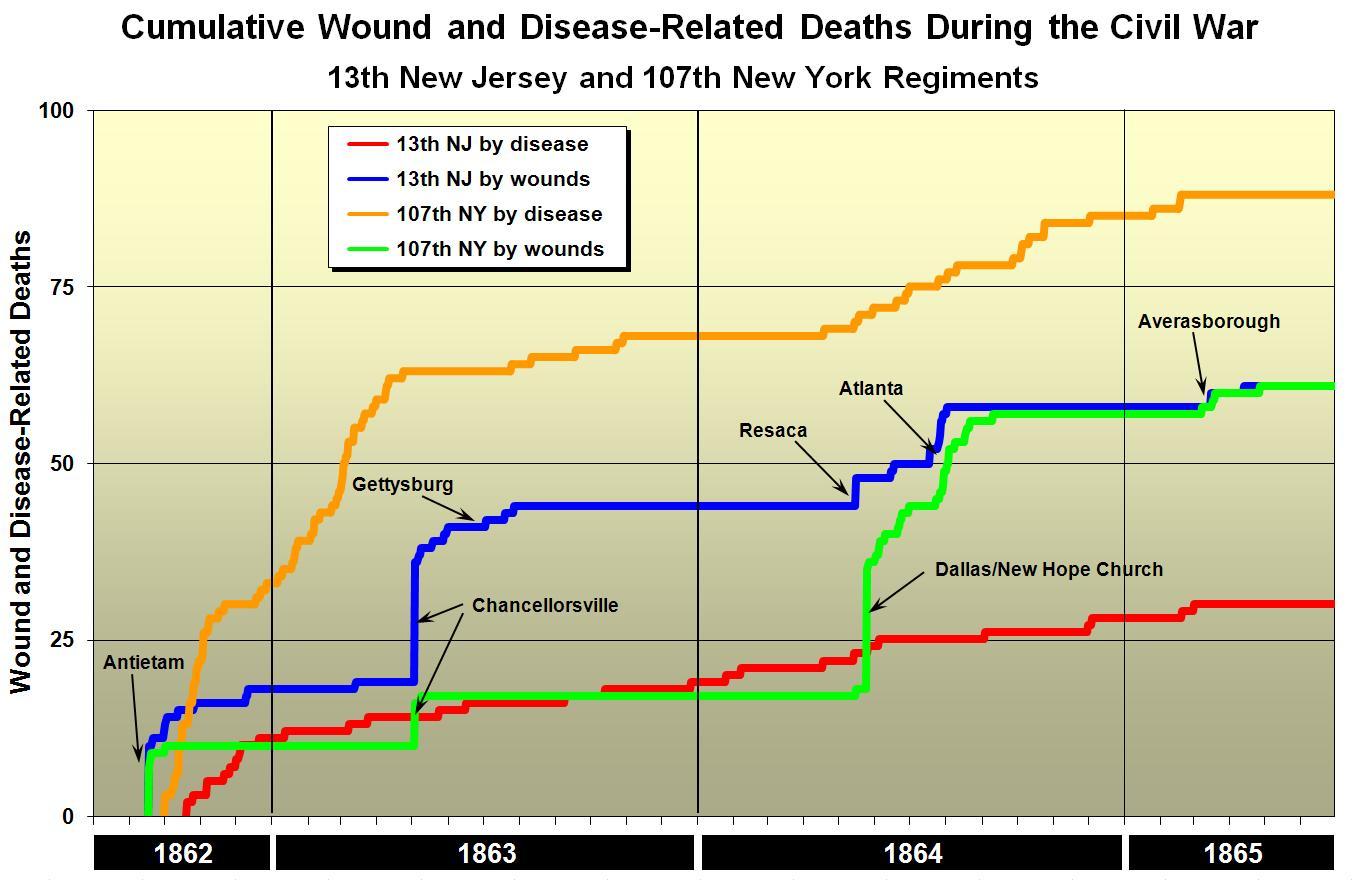

Both regiments left Maryland Heights at the end of October 1862, but disease-related deaths continued. By the time Christmas arrived that year, the death toll due to sickness rose to 32 in the 107th and 11 in the 13th. By the time spring ended in 1863, sickness and disease would claim 44 men in the 107th compared to just 14 in the 13th. By war’s end, when both regiments were mustered out of service in early June 1865, the total number of deaths due to sickness and disease reached about 90 in the 107th, three times as many as the 30 who died in the 13th. Comparatively, both regiments suffered about 60 deaths each due to battle wounds during the course of the war.

Joseph Couse’s body was eventually disinterred from its shallow grave on Maryland Heights, shipped north, and re-buried in his family’s plot in a small cemetery in Hector, no doubt this time in a proper coffin. He was buried with his mother Lydia who died in 1859. His father John died in 1863. Martin V.B. Demarest’s body was also disinterred from the rocky soil on Maryland Heights. He was re-buried in Antietam National Cemetery, joining several in his regiment killed during the battle.

Both men would represent the thousands who would die on hospital bed, on a cot in a tent, or even on a bed of pine branches under a makeshift lean-to, their bodies ravaged by killer diseases that would cause far more deaths than enemy bullets or shells. Indeed, letters and diaries of the time reveal that the death of a man like this had a much more profound impact on fellow soldiers than from a man falling on the battlefield. On October 20, 1862 the 13th New Jersey’s Colonel Carman wrote in his diary:

“It is singular how differently death approaches the feelings of men when stricken down on the battle field. The feeling is not much touched and the remembrance soon passes away, but when disease in its mysterious course saps the fount of life, the mind is filled with awe. Our men accustomed to seeing hundreds of dead upon the field with no horror looked awe-stricken at these visitations of death.”

Thank you for this interesting and informative post. I was especially surprised to read the last point: that death from disease impacted fellow soldiers more acutely than battlefield deaths. I had always assumed that the former would have been dismissed as inglorious and thus somewhat shameful. But you convey so well here how the men cared night and day for their sick comrades, which would have deepened their bonds and thereby made the loss more hurtful. I wonder: if rural vs. urban upbringing was such a large factor in soldiers’ succumbing to disease, were there many more such Confederate than Union deaths?

Another question: Are the deaths from disease included in the overall figures we read of Civil War combatant deaths, which has often been estimated at around 620,000 (until more recent experts have upped it to as many as 850,000)?

These are good questions. I came across a number of letters, diaries, correspondence to newspapers, and other writings that particularly mention how the suffering and deaths due to disease seemed to impact the soldiers more than battle deaths. In fact, after I wrote the article, I came across another quote in a well-written book I’m reading on Garfield’s assassination called ‘Destiny of the Republic’. The author quotes Garfield during his time in the Civil War where he says “this fighting disease [typhoid] is infinitely more horrible than battle.” I can’t explain it either. This is part of the reason why I’ve taken a particular regiment and put it under a microscope to try to help me understand the reasons men joined up, what their experiences were, their religious faiths, reasons for desertion, what happened to them after the war, etc.

I can’t speak on the death rate due to disease among Confederate troops, but I’m sure there are sources for that. But I wonder if a farmer in the deep south was more (or even less) susceptible to certain diseases than, say, a farmer from Maine. I’m pretty sure though that the Civil War deaths that are quoted (620k-850k) include all deaths (battle, disease, accidents, exposure, etc.)

The Confederates may have suffered more from disease because of their lack of food and medical supplies.

This article is excellent and deals with a subject not often discussed. I hope the author is expanding it into a manuscript for journal submission. I had three ancestors who died of typhoid fever in the war, two of them being a father and son.

I think you are right about that because the sheer number seems far too great for combat deaths alone when one mentally adds up well-known death figures for the major battles. Your question about differences in immunity in rural people of the South and North is intriguing. In our modern world we have changed our environment so much, but back then the South was covered with swamps and warm-weather diseases proliferated. Now we tend to think of Northerners who brave the snow and cold as more hearty, but at that time perhaps it was the Southerners who were more so by surviving such hardships as regular yellow fever epidemics. I am reminded of General Sherman’s great regret after his son Willie died. He blamed himself for bringing his family down into the climate of the South.

Looking forward to more posts from you, and many of us would be interested in some of the other areas you mention: religious faith, reasons for desertion, etc. For example, what happened to your ancestor who deserted? Did he/could he go home? Did he ever return to the Union Army? I have also wondered what became of those deserters who crossed over to the other side. Were they taken prisoner? or just went on to start a new life in another place?

Thanks for your work.

My ancestor went to Westchester County, New York after deserting. He was eventually discovered, arrested, and sent to Camp Distribution in Virginia. After awhile he was assigned to the 33rd New Jersey until the end of the war. It becomes a little murky at this point, but I don’t believe he received an honorable discharge and therefore could not apply for a pension. He lived most of the remainder of his life in Nyack, NY, basically never retiring. He was a shoemaker pretty much up to his death in 1915 at the age of 91.

There were many others like him and I hope to do an article at some point about where men went after deserting, showing a few examples. It takes some detective work, but some changed their names and joined other regiments. Others took their families and moved west. I found one in the 13th who went to Canada briefly. A handful went to New York City where it was easy to ‘get lost’, especially in the ethnic neighborhoods. Interesting stuff!

My husband’s grandmother,Maud Bond Hyatt, was the niece of Joseph Couse(daughter of his sister,Charlotte or Lottie Couse and James H Bond). Her husband Fredrick Hyatt(son of Mortimer Hyatt and Lavina Mathews Hyatt) was the nephew of Lafayette Hyatt who also served in the 107th and deserted following the Battle of Antietam after they made camp on Maryland Heights. Both Lafayette and Joseph were 19 when they enlisted in Burdett,NY on July 25,1862. Joseph actually was wounded from an exploding shell in the battle of Antietum and as noted was the first in the 107th to die at Maryland Heights camp of congestion of the brain on October 1,1862.He was buried with military honors in a coffin made of old fence boards by Sergeant Abram Whitehorn in the garden in the rear of an” old Mr Wessell’s house” which stood near the camp. Corporal Edward Kendall from Tyrone NY commanding the firing squad. (From Letter of Edward Kendall to his father Sept 29th,1862 and History of Tioga,Chemung, Tompkins,and Schuyler Counties 1879)

Following the war, upon their return to Schuyler County NY,on June 9,1865, a grand dinner was held for the returning officers and men of the 107th’s H company at the Montour House in Havana(now Montour Falls) NY at which his burial was mentioned in a speech given by Hull Fanton( adjutant of the company)

“Ah!, that never to be forgotten burial: the muffled drums, the funeral march, the sad and mourning company, as his remains were conveyed to their resting place in the little garden in the rear of old Mr. Wessell’s The desolation of fever, the sick in the open air and the old log barn, the long line of graves above Harper’s Ferry on the heights of Bolivar. My old comrades, these things you cannot forget for you were there and saw them as I did”(From Havana Journal article June 17,1865)

Sadly of the 98 men on Company H’s original roster only 34 returned,29 being at the Montour House that night.

My further research indicates that Joseph Couse’s remains were re- buried in the National Cemetary in Marietta,Georgia, and not with his parents,John and Lydia, in our local Logan cemetary. If you have evidence of the latter,please inform. Also, if anyone knows what happened to Lafayette Hyatt after he deserted, I would appreciate that information. Mrs Eric Lokken,Burdett NY