When War Came: One Family’s Encounter With America’s Civil War…Part 1

The passengers jostled to and fro as they steered their carriage and wagon over the rutted roads of Hanover County and onto the farm lane that led to the Watt farm near Dr. Gaines’ grist mill, northeast of Richmond. It was August, and as the caravan of excited children and their parents made its way toward grandmother’s farm the smells of late summer wafted across the fields and from the orchards with scents of blooming roses, apples, and peaches.[1] The nearer they got to the plain, square farm-house the more excited they became, full of anticipation for the affection about to be doled out as only their grandmother, Sarah, could do. These had become annual visits—pilgrimages of sorts—to visit the family matriarch, and these were times to be remembered.

In the 1850s, the bustling farm, known as Springfield, was a playground for the Watt grandchildren, who had spent the early mornings and late afternoons of their visits exploring the reaches of grandmother’s dominion. And to them it was expansive—a whole world hidden from the outside, a secret place atop a plateau on the eastern banks of the sluggish Chickahominy River. Margaret, a granddaughter, remembered the farm as being “shut off by a body of woods from the public highway, and there were no signs of a human habitation except one house.” The family would often laugh, joking that the farm was in actuality “the off corner of the world, the jumping off place, and vowed that the most daring and indefatigable explorer would never be able to find it.”[2] Watt’s grandchildren, explorers in their own right, spent hours wandering off on adventures to the far reaches of this seemingly secret place, from the banks of the Chickahominy to Boatswain’s Creek on the opposite slope. Grandmother’s farm was a perfect playground.

Hugh, Sarah’s husband and Margaret’s grandfather, likely died in the latter half of the 1850s, leaving Sarah to manage the farm with the help of their son, Peter. By 1860, Springfield consisted of 529 acres, nearly half considered “improved.” From these fields the Watts harvested wheat, corn, potatoes, oats, and other crops for sale at market. The orchards provided fruit. Six cows provided milk, eight provided beef, and 17 swine supplied the farm with pork. Two horses, three mules, and five oxen pulled the farm’s wagons, plows, and other implements.[3]

While the management of the farm fell to Sarah and her son, the labor came from her enslaved human property. The 1860 census indicates that Watt owned 28 human beings, equally divided between male and female. More than half, peculiarly, were under age ten.[4] In recounting her arrival at grandmother’s, Margaret specifically remembered the presence of these youngest slaves, whom she described as “a gang of little darkeys” who “stood staring and grinning and bobbing their woolly heads.”[5]

Sarah was 77 when Virginia declared its secession from the United States in 1861 and when nearby Richmond became the capital of the Confederacy. By then, her grandchildren were mostly grown, and the visits to grandmother’s had become less frequent. Three grandsons enlisted, joining the 15th Virginia, an infantry regiment raised from Richmond and surrounding Henrico and Hanover counties. With Richmond as the capital and a likely objective for the Union’s army and navy, Sarah’s grandsons could reasonably expect to see action in familiar places. If Margaret’s post-war reflection represents the thoughts of her brothers in the spring of 1862, however, they did not expect that their childhood playground would bear witness to some of the war’s most brutal fighting. “Little we thought,” remarked Margaret, “that…the name of the ‘Watt Farm’ would go down in history.”[6]

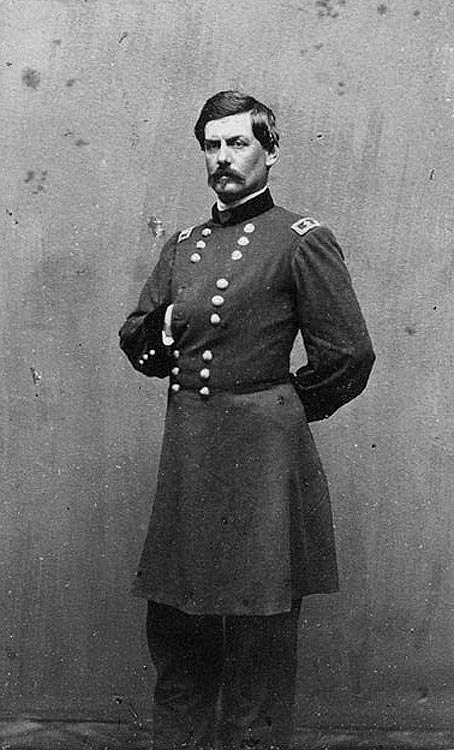

In the aftermath of the Federal debacle at Manassas in July 1861, President Abraham Lincoln summoned George McClellan from western Virginia to Washington, D.C., to assume command of what would become the Army of the Potomac. A thorough, methodical planner, McClellan was slow to move his army from Washington toward his objective, Richmond. By mid-March 1862, after nearly eight months of preparation and much prodding from Lincoln, McClellan began moving his forces by ship from the outskirts of Washington to Fort Monroe at the tip of the peninsula between the York and James rivers. As McClellan’s army moved slowly toward Richmond, the Confederate forces commanded by Joseph Johnston withdrew to the outskirts of the Confederate capital, west of the Chickahominy.

The news of Johnston’s withdrawal was delivered to Sarah’s granddaughter, Margaret, by her mother, who had recently been staying with the 77-year-old Watt, lately suffering from a serious illness. “One day mother unexpectedly returned and shocked us with the tidings that the Confederate army, now rapidly approaching, would take a position in defense of Richmond on the other side of the Chickahominy, leaving our whole section in the Federal lines,” recalled Margaret, who returned to Springfield with her mother, finding the place quiet and calm. As night fell, the glow of campfires revealed the Confederate positions to the west. A slave returning to the farm from Richmond brought messages from Margaret’s brothers, whose regiment was encamped nearby.[7]

As the Confederates withdrew to new positions closer to the city, the Federal forces pressed forward, taking up a position opposite the Confederates and within miles of Richmond—so close, in fact, that Federal soldiers kept time by tolling church bells in the city. With the Confederate withdrawal and the Federal advance west of the Chickahominy, Springfield was behind Union lines. Soon squadrons of Federal cavalry passed through the farm, as did stragglers from infantry regiments; Sarah Watt’s farm was no longer the “off corner of the world.”

There was a profound uncertainty in living behind enemy lines, as it was unclear how civilians and their property would be treated; the sight of enemy forces was unnerving. Margaret remembered Federal infantrymen visiting the house on one occasion, wishing to purchase milk, butter, and eggs. They “did not attempt to enter the house or to disturb anything outside. Nor were they noisy or disagreeable. Our own soldiers could not have behaved any better,” she said. Margaret credited their conduct to the character of their commander, McClellan, whom she believed was a “Christian gentleman” who “maintained perfect discipline in his army and strictly observed the rules of civilized warfare.” Yet despite the cordiality and professionalism of these Federals, it was clear that violence would soon literally explode nearby. “At night I watched the light of my brothers’ camp fires, and by day trembled as the house rocked with the roar of cannon throwing shot and shell into their camp,” remembered Margaret. “There was frequent skirmishing, daily cannonading, and hourly expectation of a terrible battle.”[8]

McClellan prepared for a siege of Richmond; however, an unusually wet spring and subsequently muddy roads slowed his advance and the movement of his heaviest artillery. While skirmishing and exchanges of gunfire became normal, it was not until May 31 that the armies collided in a pitched battle at Seven Pines. While the battle of Seven Pines changed very little, the severe wounding of Joseph Johnston had a profound effect on the immediate defense of the rebel capital, as President Jefferson Davis appointed Robert E. Lee as commander of Confederate forces around Richmond—forces that largely would make up his eventual Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee realized the predicament that he, his army, and Richmond faced. Despite McClellan’s claims to the contrary, it was the Confederates who were at a numerical disadvantage, and the city’s ability to withstand a siege was unlikely. Reports suggested that the disposition of Federal forces presented an opportunity to not only loosen McClellan’s grip, but to drive the Federals from Richmond’s gates entirely. Lee determined to consolidate the bulk of his forces on the east side of the Chickahominy and attack the Federal right flank near Mechanicsville. On June 26, Confederate forces commanded by A.P. Hill, James Longstreet, and D.H. Hill attacked the Federal Fifth Corps, commanded by Fitz John Porter, suffering significant losses and a tactical defeat. But by evening, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s command had arrived from the Shenandoah Valley and was positioned to descend on Porter’s right flank the next morning.

McClellan believed his position was untenable, but time was needed to move his army away from Richmond and to relocate their supplies from White House Landing on the Pamunkey River to a location southeast of the city on the James. Before dawn on the morning of June 27, Porter’s men withdrew from their positions along Beaver Dam Creek and marched to a new position on heights just beyond Gaines’ Mill that army engineers had selected for its superior defensive qualities. Sarah Watt’s farm was just hours from becoming a battlefield.

Christian E. Fearer is a senior historian for the federal government and has served as a historian for elite special operations forces in Afghanistan. He previously worked for the National Park Service at sites in Pennsylvania, Alaska, and Virginia, including Richmond National Battlefield Park. Fearer studied history at West Virginia University. He currently lives in St. Petersburg, Florida. The thoughts, views, and opinions expressed by the author are entirely his own and do not reflect those of the federal government, its departments, or its agencies.

[1] M.J. Haw, “My Visits to Grandmother,” Christian Observer, 18 May 1910, 22.

[2] Ibid.

[3] 1860 Hanover County Agricultural Census, 13.

[4] 1860 Hanover County Slave Census, 412.

[5] Haw, “My Visits to Grandmother,” 22.

[6] Ibid., 23.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

As a Civil War history buff, I read with gusto anything about that conflict. I enjoyed your “Part One” and look forward to subsequent posts.

Glad to have you reading, Jim.