More than Mountains Separated Them

Today we welcome guest author Gordy Morgan. Gordy hails from the Youngstown, Ohio area. Gordy Morgan is a life-long history buff who became intensely interested in the Civil War during the Glory/Ken Burns The Civil War era. He is editor of Drum and Bugle Call, the newsletter of the Mahoning Valley Civil War Round Table, located in northeast Ohio, and serves as its program director. Gordy earned a Master’s degree in Professional Writing and Editing from Youngstown State University in 2012.

When on May 23, 1861 the majority of Virginia’s adult white males voted to secede from the Union, many of them living in her counties west of the Allegheny Mountains still loyal to the federal government didn’t go with them.

“There were really always two Virginias,” says W. Hunter Lesser, author of Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Nation Divided. “Many of the issues dividing North and South at the time were similar to the issues dividing East and West Virginia,” he adds, particularly slavery.

Almost from its adoption the Virginia Constitution favored the slave-holding easterners, Lesser says, adding that not much tax money was sent west. Also, budding industry in Western Virginia, bolstered by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad running through it, tied the independently-minded people there more closely with Mid-Westerners than with the slave-holding aristocrats in the predominantly agrarian East.

The most important difference, however, was slavery, which existed in Western Virginia but was restricted to the river valley areas. In 1860, the number of slaves west of the mountains was only 5% of the total number of slaves in the entire state, Lesser says. Farming was mostly subsistence in nature with very little plantation agriculture.

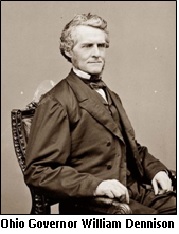

“The war was just an excuse,” according to Lesser, “for the West to split from the East.” And war did come, spurred on by the desire of Ohio’s governor, William Dennison, to protect his state.

Because Americans of that era mistrusted large, standing armies, the regular army of the United States numbered less than 17,000 soldiers, and these were scattered throughout the frontier. National security relied on active state militias serving as a vast reserve to be enlisted in the event of an emergency. Such an emergency arose when Confederates fired on and forced the surrender of the Federal garrison of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, prompting President Abraham Lincoln to call for 75,000 volunteers to repress the growing rebellion.

Ohioans responded enthusiastically to Lincoln’s call, filling their quota of thirteen regiments for national service in a matter of days. However, Ohio’s Adjutant General continued to accept units, which resulted in there being a large number of volunteers still in Columbus—enough to fill more than ten additional regiments. Governor Dennison, in what Lesser calls a “bold move,” mustered them into service for ninety-days as Ohio militia. Among these state militia units was the 19th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, which included companies from Mahoning, Trumbull, and Columbiana counties.

“I will defend Ohio beyond, rather than on, her border,” promised Dennison, and he took immediate steps to do just that. One of his first moves was to hire a talented 34-year-old ex-West Pointer and Mexican War veteran named George Brinton McClellan to command his volunteers.

Dennison was eager for action, but McClellan advised caution. If he crossed the Ohio River without cause, “there was fear that many would go to the Confederacy,” Lesser says. Virginia, at this point, had not yet voted to secede, and even though there was strong Union support in the region, itwas not overwhelming. Lesser characterizes Western Virginia in 1861 as a “checkerboard” with hot beds of sympathies scattered about.

However, once McClellan decided to invade Western Virginia it was important that he occupy it so that those citizens who were wavering in their loyalty would, according to Lesser, “come to the Union, and that’s exactly what happened.”

He wouldn’t have to wait long to act. On May 24, the day after the secession referendum, the General-in-Chief of Federal forces sent McClellan a message informing him that Confederates were gathering around the town of Grafton, some ninety miles east of the Ohio River where a branch of the B&O meets the main line from Wheeling. The B&O was vital to McClellan’s plans because it would be his army’s life line, and the young general would go to great lengths to protect it. When Confederates “burned bridges west of Grafton on both lines of the road” the next day, according to Lesser, McClellan had the trigger that he felt he needed to legitimately invade the sovereign state of Virginia.

McClellan, in what Lesser believes was a savvy move, “sent Western Virginia troops across first” so that it would look like heroic Virginians were coming to rescue family and friends. However, it was mostly a symbolic gesture, he says, because following closely were “Ohio and Indiana volunteers.” After securing the B&O, Union troops marched south, surprising and scattering the Confederates at the small town of Philippi in the first land battle of the Civil War.

The Rebels retreated south toward the Tygarts River Valley, stopping to block “the two major turnpike passes through the mountains,” Lesser says, at Laurel Hill and Rich Mountain.

Because of the formidable nature of the Rich Mountain position, it would take fewer men to defend it. Therefore, the Confederate commander in Western Virginia, Brig. Gen. Robert Seddon Garnett, placed the majority of his troops at Laurel Hill, twelve miles to the north.

McClellan’s intention was to move south to get around Rich Mountain, block theturnpike beyond, and “trap General Garnett at Laurel Hill,” according to Lesser.

The job of planning the attack fell to Brig. Gen. William Starke Rosecrans, an Ohioan by birth. Rosecrans, aided by a local guide, led his 2,000-man brigade of three Indiana regiments and the 19th Ohio in a rainstorm along an “unknown path” to get behind the Confederates on Rich Mountain.

Rosecrans hoped to surprise the Rebels, but Lieut. Col. John Pegram, who commanded the Confederates on Rich Mountain, knew he was coming—he just didn’t know from where. Pegram placed a small force of about 300 men with one cannon along the pike near the mountain’s peak to alert him.

When General Rosecrans finally attacked, he sent his Indiana regiments in first, keeping the 19th Ohio in reserve. This first assault was repulsed, Lesser says, because the outnumbered Confederates, believing they would be reinforced, “fought valiantly.” Aiding the defenders was the fire of the lone cannon, which demoralized the green Federal troops. “Rosecrans knew he had to silence it,” says Lesser, and, posting himself conspicuously in front of his men, the General led a bayonet charge.

The 19th Ohio, approaching the enemy’s vulnerable right flank, delivered two “really strong volleys” that broke the defenders resolve and forced them to retreat. According to Lesser, the Ohio volunteers “really sealed the deal during the battle.” The remainder of Pegram’s men evacuated their works and surrendered a few days later.

When he learned that Rich Mountain was lost, General Garnett knew he could not hold his position on Laurel Hill and ordered a retreat south. However, his scouts misidentified Confederates in the town of Beverly as Union troops and, believing their escape route blocked, Garnett’s men scattered eastward through the mountains. Union soldiers pursued and caught up to them at Corrick’s Ford along the banks of a small offshoot of the Cheat River some thirty miles to the north. Here Union troops killed General Garnett.

Fighting between organized Union and Confederate armies in the Alleghenies would continue for the next few months at places with names like Cheat Mountain, Camp Bartow, and Camp Allegheny, but McClellan and his army had “established a Union bulkhead that was never really relinquished,” Lesser says.

Lesser asserts that the Western Virginia campaign was a “proving ground for many of the bright lights” of the war, and cites George McClellan and Robert E. Lee as examples. With his reputation enhanced by victories in Western Virginia, McClellan would be transferred east and given command of the shattered Federal army regrouping in Washington, D.C. following the Union disaster at Bull Run on July 21st.

And although his later successes commanding the main Confederate army to the war’s end would make him the most revered man in the South, in Western Virginia Lee failed. But having failed, Lesser believes, Lee had the opportunity to learn from his mistakes.

For the remainder of the war, Western Virginia became the site of vicious guerrilla warfare, reflecting the divided loyalties of the people. But because the Confederate army was not a viable threat, loyal Union men could hold their own secession convention without fear of retaliation.

On December 31, 1862, President Lincoln signed the West Virginia Statehood bill into law. Six months later, on June 20, 1863, West Virginia officially became the 35th state of the Union.

Politically, the “creation of West Virginia is the biggest legacy of the war in the state,” and it was a “direct result of the Union occupation,” Lesser says. Had the Governor of Ohio not been willing to vigorously prosecute the defense of his state, and had Ohio and Indiana volunteers not been ready to move at a moment’s notice, the history of the Civil War—and the map of the United States—might not be what we know today.

An interesting article on a neglected aspect of the war. Having researched Ambrose Bierce’s service in the Ninth Indiana I delved into this campaign too. I think the struggle for control of the Ohio Valley in general was a major factor in the ultimate victory of the North. North of the Ohio there was strong pro-Secessionist sympathy, just as there was strong Unionist sympathy on the south bank. Western Virginia and then Kentucky were crucial first steps in the war. I noticed the image of a book on the campaign I hadn’t been aware of, hope to put it on my to do list of books to read. Again, thanks for the good article.