The Wounding of James Longstreet: Part One

-Authored by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White-

The Confederate flank attack through the Spotsylvania Wilderness had been an overwhelming success, surprising the Federal army and sending them into chaotic retreat. Now, the general wanted to push his advantage. His men, weary from their long morning march and the fight that followed, would still do anything he asked of them even though many of them were bogged down and lost in the thick, confusing foliage. He rode with his staff officers out ahead of his men, looking for a way to continue the attack.

But from the woods along the road, gunfire erupted. Confused Confederates had opened on the party of horsemen, not realizing they were friends. Bullets tore through the general’s party.

And among the casualties was James Longstreet himself, shot through the neck—shot by his own men.

One year and four days earlier, less than four miles away, Longstreet’s fellow lieutenant general, Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, had been accidentally wounded under similar circumstances. While Jackson’s wounding is frequently cited as one of the pivotal events of the Civil War, Longstreet’s wounding is frequently forgotten about—yet the absence of Lee’s “Old War Horse” had a far more immediate impact on the battle and on the Army of Northern Virginia as a whole.

In fact, his impact on the battle of the Wilderness on that May 6 had already been immediate and significant. Longstreet’s First Corps had been camped in Gordonsville, some 27 miles away from the battlefield, before the fighting had started. Being the farthest away meant it took them the longest to arrive. In the meantime, the Second and Third Corps had battered—and been battered by—the Army of the Potomac.

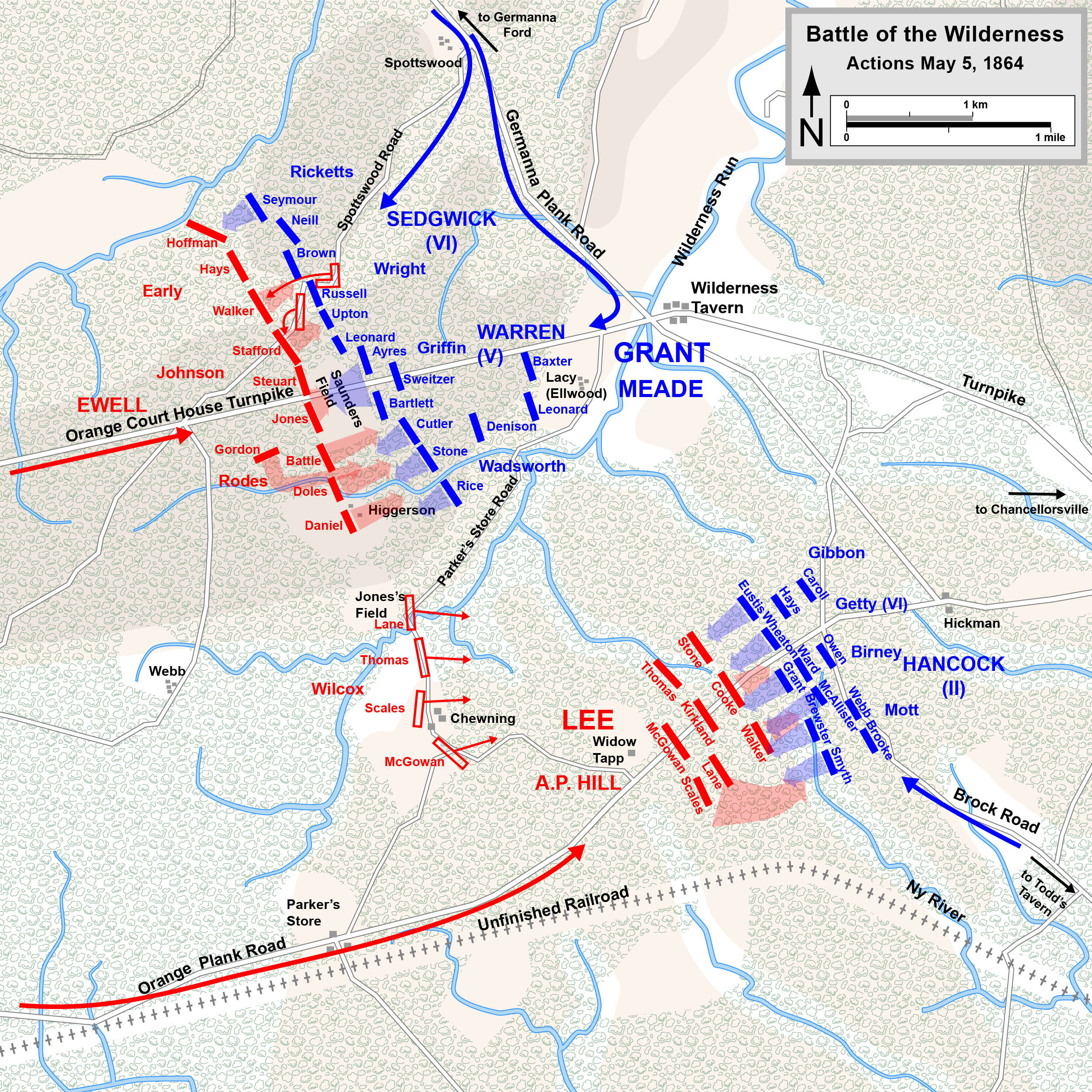

Lee had launched the attack on May 5, using two parallel roads that ran smack into the Union column, in the hopes that the dense second-growth forest known as the Wilderness would make it tough for the Federal army to maneuver, thereby evening the odds a bit. Lee had roughly 66,000 men compared to the 123,000 under the command of Ulysses S. Grant.

While the Confederates held their own on that first day of battle, a dawn attack by the Federals on May 6 threatened to overwhelm the Confederate right. Literally in the knick of time, Longstreet arrived on the field with desperately needed reinforcements. “The instant the head of his column was seen, the cries resounded on every side, ‘Here’s Longstreet. The old War Horse is up at last. It’s all right now,’” remembered one private.

Longstreet’s Texas brigade, in the vanguard, drove the Federals back nearly a mile, assisted by troops from Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina. Their counterattack secured the Confederate right and the open ground of Widow Tapp Field. “Longstreet, always grand in battle, never shone as he did here,” remembered John C. Haskell, one of Longstreet’s artilleryman.

The bulk of Longstreet’s men had never fought in the Wilderness before. They had been detailed on a foraging mission to southeastern Virginia the previous May, when the rest of the Confederate army clashed with the Army of the Potomac in the battle of Chancellorsville, just a half-dozen miles to the east. This terrain was unlike any they’d ever fought through before. The Wilderness was seventy square miles of hillocks, swales, and gullies covered by second-growth forest: young trees, whip-like saplings, short, thick, scrubby bushes, and thorny vines. One Union soldier said that even at the brightest point of the day, one could not see the forest floor because the foliage was so thick.

“The ground was covered with brush and small timber, so dense that it was impossible for an officer at any point of the line to see and other point several yards distant,” said a Vermonter, who’d soon be flushed from his position by the advancing Confederate tide.

The dust, “so thick as to reduce every tree and shrub to one uniform shade of gray,” compounded the visibility problems, remembered one of Longstreet’s staffers.

The Wilderness itself worked to blunt the Confederates’ momentum, but Longstreet would not be deterred. Using intelligence gathered by one of Lee’s engineers, Longstreet sent four brigades— George “Tige” Anderson’s and William Wofford’s Georgia brigades, along with elements of Joe Davis’s mixed brigade from Mississippi and North Carolina and William Mahone’s all-Virginia brigade—along an abandoned railroad cut that put them on the Union left flank, near the Brock Road-Plank Road Intersection. He sent his chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Moxley Sorrel, to lead the maneuver.

Sorrel would attack in concert with a push down the Orange Plank Road by Major Generals Charles Field and Richard Anderson and Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw against the center of the Federal position. By hitting the Federals in front and flank, Longstreet hoped to force them north toward the Rapidan River.

Sorrel’s flank attack drove forward “like a storm,” said one of the Georgians who was part of the attack. The results, remembered a Federal soldier swept up in that storm, was a “terrific tempest of disaster.” The converging wings collapsed the Union line, sending blue-coated soldiers retreating northward and westward. Union Brigadier General James Wadsworth would be mortally wounded along the Plank Road trying to rally his men.

Even as the flank attack continued forward, Sorrel rode back to his commander to see what the next course of action would be. “There was a pause for some time to rest the men, to get the lines straightened, and to replenish ammunition,” Haskell remembered. Longstreet warmly congratulated Field, then he held a quick council with his subordinates and staff.

“Longstreet intended to play his hand for all it was worth, & to push the pursuit with his whole force,” remembered Brigadier General E. Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s chief of artillery, who had come by just then. Longstreet detailed another flanking force to attack the new Union position that was trying to form a few hundred yards to the east along the Brock Road. He would again launch a frontal assault to coincide with the flank assault.

Leading the frontal assault would be the South Carolinian Brigade of Brigadier General Micah Jenkins, which Alexander described as one of the “best & largest” in the army. Fresh from an assignment in the Western Theater, the South Carolinians were “dressed in new uniforms made of cloth so dark a gray as to be almost black,” one observer said.

Longstreet rode at the head of the column with Jenkins, accompanied by Sorrel, Dawson, Kershaw, Wofford, and at least six others. One of Longstreet’s staffers, Lieutenant Andrew Dunn suggested that perhaps Longstreet was unduly exposing himself to danger. “That is our business,” Longstreet replied.

Further east on the Orange Plank Road, the flank attack had continued to unfold. Mahone’s brigade of Virginians, which had seen the worst fighting, had lagged behind the others. The terrain had also slowed them. “[W]e passed through marsh, swamp, and burning woods,” one of men of the Virginians said.

In the tangled forest and confusion, the 12th Virginia, which had been holding the right flank of Mahone’s brigade, got separated from the regiment next to it. The men of the 12th had to veer around one of the forest fires burning in the Wilderness, and then, following the contour of the ground, found themselves advancing along the bottom of a dip between two pieces of high ground.

Hidden from view as they were by the gully they were in, the 12th Virginia neither saw their fellow Confederates to the left nor were they seen by the reforming Federals just one hundred yards or so to their right. Ahead of them, though, across the Plank Road, they could see scattered remnants of other Federal units, and they crossed the road to do battle. Realizing they were the only unit across the road, though, the Virginians quickly “wheeled around so as to be parallel with the road,” said James E. Philips, who was in the regiment. This would bring the 12th Virginia up out of the low ground, advancing back toward the road up the northern slope of one of the hillocks they’d been skirting.

The rest of Mahone’s brigade, meanwhile, had stopped to dress ranks and reform. They were lined up between thirty-five and seventy-five yards to the south of the Plank Road. In the absence of the 12th Virginia, the 41st Virginia now held the brigade’s right flank.

With the 12th Virginia on the north side of the road, and the rest of Mahone’s brigade on the south side of the road, Longstreet and his party rode right between them at the head of Jenkins’s brigade.

Dawson recalled a jubilant Jenkins, “his face flushed with joy” at the Confederate success thus far. At Jenkins’s urging, the men “cheered lustily” for Longstreet.

And then disaster struck.

3 Responses to The Wounding of James Longstreet: Part One