Edward Thomas’ Georgia Brigade at the Battle of Jericho Mills on May 23, 1864

We are pleased today to welcome award-winning author John J. Fox III

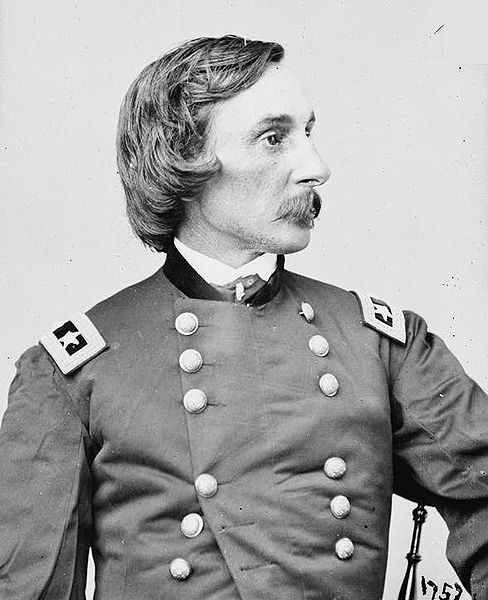

The hot afternoon sun on May 23, 1864 beat down on the backs of Brig. Gen, Edward Thomas’ Georgians as they halted at a small hamlet called Anderson Station along the single-line track of the Virginia Central Railroad. Two days and twenty-three miles earlier, these Georgians and the rest of Maj. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s division had departed the carnage at Spotsylvania Court House and moved south to join other Third Corps units to try and again block Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant’s end run toward Richmond.

The other two corps in Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Lee’s army moved south, too, hoping to beat Grant’s army across the North Anna River. They succeeded, but the subsequent fighting to prevent the Army of the Potomac from crossing the river would fail and would add to the growing casualty lists of both armies during the Overland Campaign.

At Anderson Station, located almost four miles west of the Confederate rail supply depot at Hanover Junction, the 45th Georgia’s Frances Solomon Johnson sought some shade as he hoped to write a letter home. Johnson described the long hot march over the previous days as “weather warm, water scarce and dust in profusion.” He also admitted that “I think I am nearer worn out, dirtier and more in want of rest than I have been since I can recollect.”

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill’s Third Corps anchored the Confederate left at Anderson’s Station. Three miles northwest, a trail crossed the North Anna River at Jericho Mills. Confederate cavalry surprisingly had failed to secure this crossing. Earlier in the afternoon, lead elements of Union Maj. Gen. Governour K. Warren’s Fifth Corps had sloshed through the waist-deep water while Union engineers constructed a pontoon bridge for the artillery.

Cadmus Wilcox received orders from A. P. Hill to move his division toward Jericho Mills to investigate Union intentions. Wilcox met with Brigadier General William H.F. “Rooney” Lee. The cavalry commander mistakenly informed Wilcox that only two brigades of Federal cavalry had forded the river. Lee next reported that these enemy troopers seemed vulnerable to an attack as they had halted to cook their evening rations.

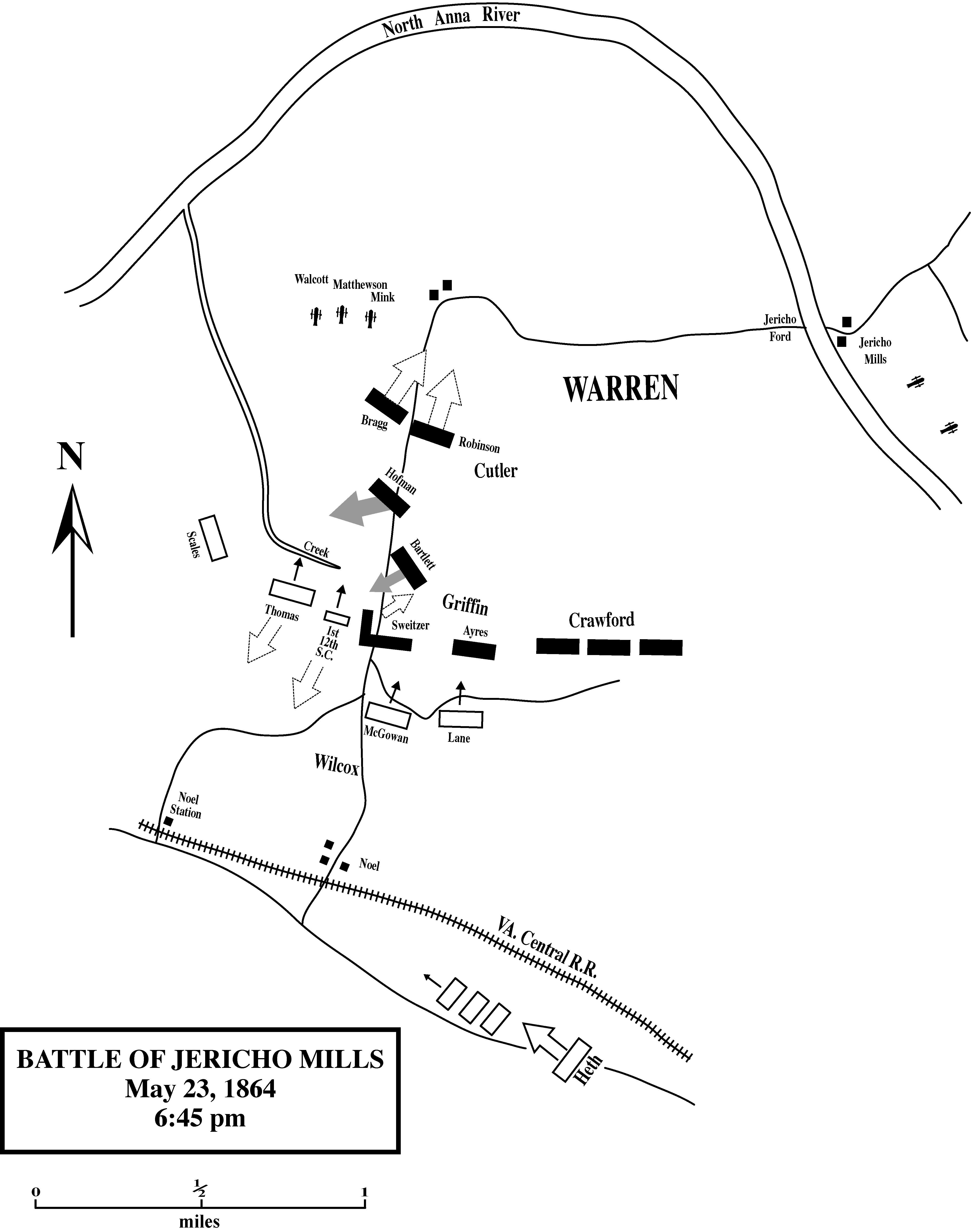

In reality, though, Cadmus Wilcox faced three enemy divisions plus at least six batteries that had already crossed the river. Federal Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford’s division deployed on the Union left with Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin’s division on the right. Brigadier General Lysander Cutler’s division remained to the rear in reserve near the river ford. Numerous Federal batteries dotted the high ground on both sides of the river.

At 4:30 P.M., Wilcox’s column marched out of Anderson Station northwest along a road that paralleled the railroad tracks. These four veteran brigades included Thomas’ Georgians, Brig. Gen. James Lane’s North Carolinians, Brig. Gen. Samuel McGowan’s South Carolinians, and Brig. Gen. Alfred Scales’ North Carolinians. Two miles later, they reached the dirt road at Noel Station that led to Jericho Mills. Three of the Southern brigades formed a line of battle perpendicular to the dirt road. Thomas’ Brigade occupied the left with McGowan’s Brigade, now commanded by Colonel Joseph N. Brown, in the middle and Lane’s men on the right. Scales’ brigade, led by Colonel William Lowrance, remained behind the rear of Thomas’ left flank to envelop the Federal line if the opportunity arose. The time was near 6 P.M. As the troops crossed the railroad tracks and headed north along the dirt road, they came under a vigorous artillery bombardment followed by sporadic skirmish fire. Thomas’ men found themselves in woods at the foot of a slope. They crossed a boggy stream and slogged uphill into scattered pines and then a thick forest.

The undergrowth made it difficult to maintain a straight line of battle. The sudden appearance of the Georgians [14th, 35th, 45th, 49th] in the dense woods surprised the skirmishers of the 95th New York and the 22nd Massachusetts. The Southerners captured several enemy skirmishers while the remainder tore away through the woods. The commander of the 22nd Massachusetts expressed frustration as he watched Thomas’ and Scales’ troops march diagonally toward the undefended Union right. He had feared a turning movement from that direction and had expressed his worries all the way up through his chain of command to Fifth Corps headquarters—all to no avail. Faced with danger, Cutler’s division received orders to move from their reserve position toward the Union right, but it proved to be too little too late.

Edward Thomas urged his Georgians forward with a yell. In the excitement of the charge, Thomas’ men angled toward the left creating a gap with McGowan’s men to the right. Colonel Jacob Sweitzer’s Union brigade, astride the dirt road, offered stiffer resistance in front of the South Carolinians. This prevented the Palmetto State soldiers from moving forward to maintain the line with the Georgians.

As Thomas’s men charged forward, they slammed head on into Col. William W. Robinson’s famous Iron Brigade from Cutler’s division. Robinson’s Midwesterners had just arrived on the line and his 6th Wisconsin linked with the right of Sweitzer’s 9th Massachusetts. This location became a hot place because Scales’ men had maneuvered around west of the Union line and now drove into the exposed right flank of the Iron Brigade. Hit from the front and right, most of Robinson’s men broke. Major Merit Welsh, 7th Indiana, wrote, “While forming in line, but before the troops on the right got into position, we were attacked by the enemy in overwhelming numbers and forced to retire some 200 yards.”

Lieutenant Colonel Rufus R. Dawes, 6th Wisconsin, experienced much frustration as he tried to extend the Union line to the right of Griffin’s division. The thick underbrush proved troublesome as his men formed into line of battle. “I immediately threw forward skirmishers to cover my front. In a few moments I heard sharp musketry and the peculiar cheer of a charging column of the enemy on my right. My skirmishers also commenced firing and falling back. When my front was cleared, I ordered the regiment to kneel and fire right oblique through the bushes in direction of the cheering.”

Dawes expressed concern when the firing to his right slackened. He sent his adjutant to find out why. Moments later the startled staff officer returned with a dire report: all the Federal units on the right had run off. Simultaneously, an enfilade fire from the right zipped amongst his men. Dawes ordered a partial change of front to meet this new threat, but he needed more men. “Finding the enemy in rear of my right, I changed front again so as to throw my line at right angles to the front of the First [Griffin] Division,” he said.

Dawes soon faced another problem. The 9th Massachusetts on his left abandoned their position. He reluctantly ordered his Wisconsin men back. This threat to the Fifth Corps’s right flank threatened to roll up the line and push the blue infantry into the river. As jubilant Confederates shoved the Federal line rearward, an overconfident Cadmus Wilcox sent a courier to find A. P. Hill and report “that the engagement was going on well and that the enemy would be whipped.”

Three Federal batteries on a ridge behind the right part of the main line now grimly attempted to hold the Confederate tide. Frantic Union officers rallied the retreating infantry around the cannons. These three batteries manned the line from left to right respectively: Battery H, 1st New York Light Artillery commanded by Captain Charles E. Mink; Battery D, 1st New York Light Artillery commanded by Captain Angell Matthewson; Battery C, Massachusetts Light Artillery commanded by Lieutenant Aaron F. Walcott.

McGowan’s two left regiments, the 1st and 12th South Carolina, moved through the woods on the right of Thomas’ men as the pressure in their front disappeared. Thomas’ men found themselves in the open along a small creek at the base of a hill. Smoke atop the hill revealed the three Union batteries, and these cannons turned their full attention on the Georgians.

At this critical moment, Charles Griffin had only one Union brigade left at his disposal. The Federal commander immediately ordered this reserve, commanded by Brig. Gen. Joseph J. Bartlett, forward to patch the opening on his right flank. The situation suddenly turned. Bartlett’s men opened a deadly enfilade fire into the open right flank of the 1st and 12th South Carolina regiments. The shock of this attack halted the Palmetto troops in their tracks. The commander of the 1st Michigan described the impact his men, accompanied by the 16th Michigan and 83rd Pennsylvania, made against the South Carolinians and then the Georgians: “We moved on a double-quick to the support of Sweitzer, and forming rapidly on his right flank poured stunning volleys into the enemy’s ranks, which, with a severe fire of grape and canister from our batteries, very much demoralized his troops.”

Federal fire struck both commanders of the two South Carolina regiments. In the ensuing confusion, blue-clad soldiers captured Col. Joseph Brown, the South Carolina brigade commander. The deadly combination of enemy infantry and artillery fire became too much, and the South Carolinians retreated. This move uncovered the Georgians’ right flank, and as they charged forward across the creek, Bartlett’s oblique fire from the right stunned them, too. At the same time, canister and case shot from the Union batteries just ahead tore holes in their front lines.

Captain Mink described the devastating effect his twelve-pounder cannons had upon the on-rushing Georgians and South Carolinians:

I brought the battery in position, and as soon as our retiring troops could be cleared from our front, I opened upon the enemy with canister, and supported by Colonel Hoffman’s brigade, of Cutler’s division, repulsed their charge and drove them from the field, firing case-shot into them until they were driven into the woods. We then kept up a fire of solid shot through the timber until the field was cleared, and our troops held a position about 1,000 yards in advance of the ground where the battle opened.

The 35th Georgia’s private Augustus J. Moon vividly recalled the carnage of this artillery fire. He watched as an explosion knocked his company commander, Captain John Y. Carter, through the air. The officer’s broken body flopped down upon a stump. Moon rushed over and tried to talk to him but received no response. Moon dragged the severely wounded officer off the stump and straightened his body out on the ground. He placed a hat over Carter’s face to shield it from the sun, and then he dashed off toward the safety of the distant railroad tracks. Just as he reached a railroad cut, a shell exploded nearby, showering him with dirt as he slid down the slope.

Cadmus Wilcox’s face grew long as the confidence of certain victory disappeared. He stared in disbelief as Thomas’ Georgians and McGowan’s 1st and 12th South Carolina regiments broke rearward in their worst performance of the war.

Thomas watched helplessly as his men dashed back toward the railroad. Confederate soldiers in other units noted the poor showing and voiced some criticism of the Georgians. Sergeant Marion Hill Fitzpatrick, 45th Georgia, described his frustration when the brigade sharpshooters fell back due to the intense fire. They expected to find the rest of the brigade behind them “but we had inclined to the right and the brigade to the left, so where I was I found no support at all in my rear.” Another 45th Georgian admitted, “I hated to run but thought prudence the better part of valor especially as I saw everybody else running the same way.”

Wilcox expressed frustration because Thomas’ men had driven in the enemy line, but then they had broken rearward themselves. The gap created when Thomas’ and McGowan’s men broke for the rear destroyed the Confederate momentum and caused the rest of the attack to collapse. The division commander placed the blame for the debacle on Thomas’ men. He wrote of the Georgia brigade, “The conduct of this brigade hither to of good reputation is inexplicable.” He claimed that the rest of McGowan’s Brigade had almost reached the enemy’s batteries when “The breaking of the Georgia brigade on its left threw the South Carolina brigade into disorder.”

An officer in the 1st South Carolina stated that as they chased enemy skirmishers up and over the crest of a hill they came to within two hundred yards of the three batteries. “It would not have been difficult to capture them by a brisk charge; but Thomas’s brigade did not come up, and the connection with the other three regiments of McGowan’s brigade was broken by a gap of at least a hundred or more yards.” He claimed that it was at this point that a severe enfilade fire from the right forced the two South Carolina regiments back.

Whether the South Carolinians or Georgians broke rearward first was unknown. Edward Thomas’ perspective on the situation at Jericho Ford remained a mystery because no written report by the Georgia commander ever surfaced. Cadmus Wilcox’s report left no doubt that he blamed Thomas for the disaster. In reality, the day might have turned out better for Wilcox if he had received better cavalry intelligence, a more timely arrival of reinforcements, and a more aggressive push by Scales’ (Lowrance) Brigade against the Union right flank.

At darkness, an angry Wilcox found the Georgians huddled in a railroad cut, and he ordered them back forward. He reportedly berated Thomas there. The division moved back to Anderson’s Station a short time later. The battle of Jericho Mills resulted in over 600 casualties in Wilcox’s Division.

Governeur K. Warren’s men suffered light casualties during this fight. Unfortunately, the Federal Fifth Corps casualty returns represented the period from May 22-June 1 and thus were not specific to the fighting on May 23.

The campaign had taken a toll on many of Thomas’ men. The constant fighting for weeks with no relief had drained many men both physically and mentally. There had not been a mail call in over two weeks. One Georgian reported that he had just taken his boots off for the first time in three weeks to sleep. “We all look very much like a horse after a weeks hard riding on the shortest kind of rations.” For many days, the men had survived on hard crackers and bacon. The gaunt stares and thin frames betrayed their hunger. The soldiers knew that if they could just halt for a short time, form a camp, then the supply wagons with food could reach them. Many, however, wondered when that time would come as Grant seemed determined to move his army to Richmond.

————

Please note that the Jericho Mills Battlefield is located north of Route 684 in Hanover County and is on posted private property.

For the author’s citations for this story, please e-mail Emerging Civil War.

————

John J. Fox grew up in Richmond, Virginia. He graduated from Washington & Lee University with a BA in U.S. History in 1981 and then served on active duty in the U.S. Army for seven years as an armor officer and aviator. His 2004 book, Red Clay to Richmond: Trail of the 35th Georgia Infantry Regiment, received the “2005 James I. Robertson Jr. Literary Prize for Confederate History” and a 2006 research award from the Georgia Secretary of State. His 2010 book, The Confederate Alamo: Bloodbath at Petersburg’s Fort Gregg on April 2, 1865, received a 2011 IPPY Award for non-fiction. His articles have appeared in numerous Civil War magazines and newspapers. His newest book, Stuart’s Finest Hour: The Ride Around McClellan, June 1862, was released in September 2013 and just won a 2014 IPPY Award. When he is not writing, Fox is a pilot for American Airlines. He lives in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

1 Response to Edward Thomas’ Georgia Brigade at the Battle of Jericho Mills on May 23, 1864