No Bluffing the King of Spades: Digging in along Hatcher’s Run

The Army of Northern Virginia had a thirty-seven mile front to defend during the early months of 1865. Its commander wanted to guarantee the earthworks protecting Richmond and Petersburg were up to his standards.

“Opinions seem to differ as to Gen. Lee as a tactician or an invader,” commented a Union counterpart, “but all agree that when it comes to defensive operations, ‘Old Bob’ understands his business.”

Robert E. Lee took command of the principal Confederate army in the summer of 1862, when the Army of the Potomac had backed it against the capital’s defenses. Secure in the opinion that the massive fortifications whose construction he oversaw would provide a safe fallback point, Lee executed a series of vicious attacks that drove the cautious George B. McClellan’s army away.

Two years later the Union forces returned but this time they would not leave.

After the month-long Overland Campaign did not deliver Richmond as its costly prize, Ulysses S. Grant set his sights on Petersburg to the south but was unable to storm his way in. The Union commander settled on squeezing the cities and their protective army into submission by slowly chipping away through the summer and autumn of 1864 at the supply network outside of the Confederate fortifications. By winter he had stretched Lee’s army to have to guard thirty-seven miles worth of defenses. Only two supply routes remained: Boydton Plank Road and the South Side Railroad.

Hatcher’s Run–“a very tortuous stream”–marked the furthest point south along the lines.

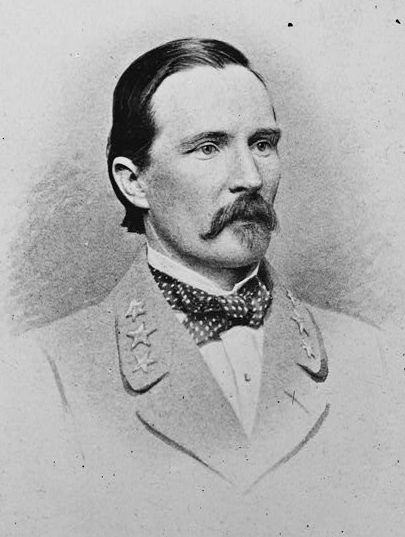

Lee ordered Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Third Corps to construct a fort near the run. “General Hill became ill after the order was received, and the construction of his fort was not pressed,” recalled Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, commanding the Second Corps. “Indeed, the weather was so severe and the roads so nearly impassable that there was no urgent necessity for haste.” Maj. Gen. Henry Heth was to have overseen the construction in Hill’s absence.

Lee ordered Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Third Corps to construct a fort near the run. “General Hill became ill after the order was received, and the construction of his fort was not pressed,” recalled Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, commanding the Second Corps. “Indeed, the weather was so severe and the roads so nearly impassable that there was no urgent necessity for haste.” Maj. Gen. Henry Heth was to have overseen the construction in Hill’s absence.

On a cold January morning in 1865, Lee called both Gordon and Heth to accompany him as the senior general inspected the line. Part of Gordon’s command extended the line back from Hatcher’s Run to the northwest.

“General Gordon, how are you getting along with your fort,” asked Lee as the trio rode south from Heth’s quarters at the Pickrell house. “Very well, sir. It is nearly finished.”

“Well, General Heth, how is the work upon your fort progressing?”

Heth struggled to find a response. With only a temporary assignment as Third Corps commander he had not taken the time to assess the earthworks that far down the line. Finally he offered: “I think the fort on my side of the run is also about finished, sir.”

The three generals arrived at Hatcher’s Run and found construction hardly even begun on the the fort. Lee fixed his gaze on the vacant ground before directing his attention on Heth. “General, you say the fort is about finished?”

“I must have misunderstood my engineers, sir,” Heth replied.

“But you did not speak of your engineers. You spoke of the fort as nearly completed.”

General Heth had a pretty good setup going during the winter at Petersburg. A friend of his, Major Benjamin F. Ficklin, was a blockade runner in North Carolina. “During the winter of 1864-5 Ficklin wrote me if I would send a wagon to Wilmington he would load it with good things,” Heth recalled in his memoirs. “I did so. The wagon was loaded with canned goods, coffee, tea, sugar, hams, twenty gallons of brandy, and the same amount of whisky, a dozen boxes of fine cigars, etc.”

General Heth had a pretty good setup going during the winter at Petersburg. A friend of his, Major Benjamin F. Ficklin, was a blockade runner in North Carolina. “During the winter of 1864-5 Ficklin wrote me if I would send a wagon to Wilmington he would load it with good things,” Heth recalled in his memoirs. “I did so. The wagon was loaded with canned goods, coffee, tea, sugar, hams, twenty gallons of brandy, and the same amount of whisky, a dozen boxes of fine cigars, etc.”

Included among the luxury items was a fine black horse “which was the admiration of the army.” Heth probably regretted choosing to ride it that morning. The animal had evidently also grown agitated with its rider and began to thrash about under the saddle.

“General, doesn’t Mrs. Heth ride that horse occasionally?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, general, you know that I am very much interested in Mrs. Heth’s safety. I fear that horse is too nervous for her to ride without danger, and I suggest that, in order to make him more quiet, you ride him at least once every day to this fort.”

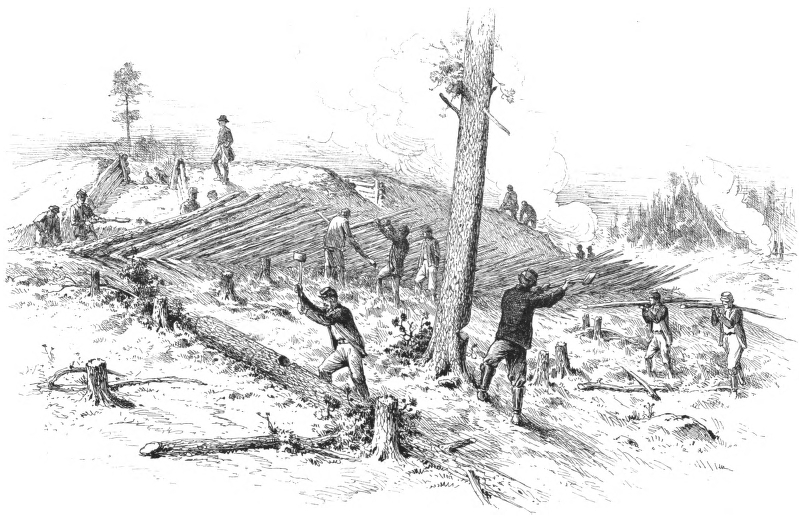

With that subtle reprimand the three continued on. The scolded general rode considerably in the rear the rest of the way. By the early February engagement at Hatcher’s Run, the Confederate fort stood fully functional in the way of Grant’s Seventh Offensive against Petersburg.

Though he does not call Heth out by name, the story of his rebuke can be found in John B. Gordon’s Reminiscences of the Civil War (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904).

It is also not certain precisely where the referred-to fortification is located, but it is likely along a stretch of Civil War Trust ground that protects some of the best preserved earthworks related to the Petersburg Campaign.

In the past month I have enjoyed the opportunity to construct a trail around these earthworks that will allow the first public access to this section of the Confederate line. I’ve learned from Heth to give honest updates along the way of the project’s completion.

Reblogged this on Poore Boys In Gray and commented:

During the Civil War, Northern and Southern armies usually waited for the spring thaw before starting military operations. But in 1865, U.S. General Ulysses S. Grant didn’t wait for spring.

On February 6, 1865, William Poore and his comrades in Harris’ Brigade headed back to their camp after spending time at a forward position near Dabney’s Mills. They perhaps looked forward to a warm camp and relief from the ice and cold. Before they could reach the camp an order came to turn about and head toward the enemy.

William and his fellow graycoats ran for the next 4 miles down Boydton Plank Road. The road led from Petersburg to the southwest. Where it crossed Hatcher’s Run, the brigade moved 2 miles through a swamp and thick woods toward the sound of heavy firing.

The firing came from a Union cavalry division and most of two federal infantry corps. U.S. Brigadier General David Gregg’s cavalry division had galloped up on February 5 to destroy Confederate supply wagons they believed to be moving along Boydton Plank Road.

As it turned out, little traffic moved on the road, but the federals didn’t know that until Gregg’s troopers reached the road. Once over the plank road, the Northerners threatened to cut the Southside Railroad, Petersburg’s last rail link to the west and south.

To protect Gregg’s eastern flank, Major General Gouverneur K. Warren with the V Corps crossed Hatcher’s Run and dug in on Vaughan Road. To protect Gregg’s western flank, Major General Andrew A. Humphreys’ two divisions of II Corps dug in near Armstrong’s Mill. Confederate divisions under Major General Henry Heth and Brigadier General Clement A. Evans attacked the Yanks that afternoon. But the bluecoats beat them back.

Over the next 24 hours, more troops arrived for both sides.

William and his comrades in Major General William Mahone’s Division, under the command of Brigadier General Joseph Finegan, arrived on February 6. The other brigades in the division had already arrived and gone into action when William and his comrades got into the line on the left of General John B. Gordon’s Second Corps. This must have been about 5 p.m.

William and his fellow infantrymen charged the Yankees and drove the enemy nearly 2 miles. The federals fell back from Boydton Plank Road. That night snow, hail, and sleet fell as both sides dug in. The next day, the federals probed rebel defenses, but no major fighting took place.

The Confederates had succeeded in protecting Boydton Plank Road, but the federals had succeeded in extending their lines 3 miles closer to the Southside Railroad and further south of Petersburg. Petersburg’s thin line of de-fenders stretched thinner again.

“I must have ‘understood’ ( or misunderstood ?), my engineers…” Still an interesting read.

Thanks for the catch! I must have misunderstood Gordon’s quote… Fixed now!

Opposite the photo of Gen.Heth is a description of the luxuries provide him by a friend in Wilmington–this at a time when Gen. Sherman was marching North into S. Carolina after capturing Atlanta and Savannah, Gen. Thomas had defeated Gen. Hood at Nashville, Gen. Grant was besieging Gen. Lee, the Confederacy railroads were worn out and the Confederate troops could not be adequately feed, clothed or otherwise supplied.

Hmmmmm