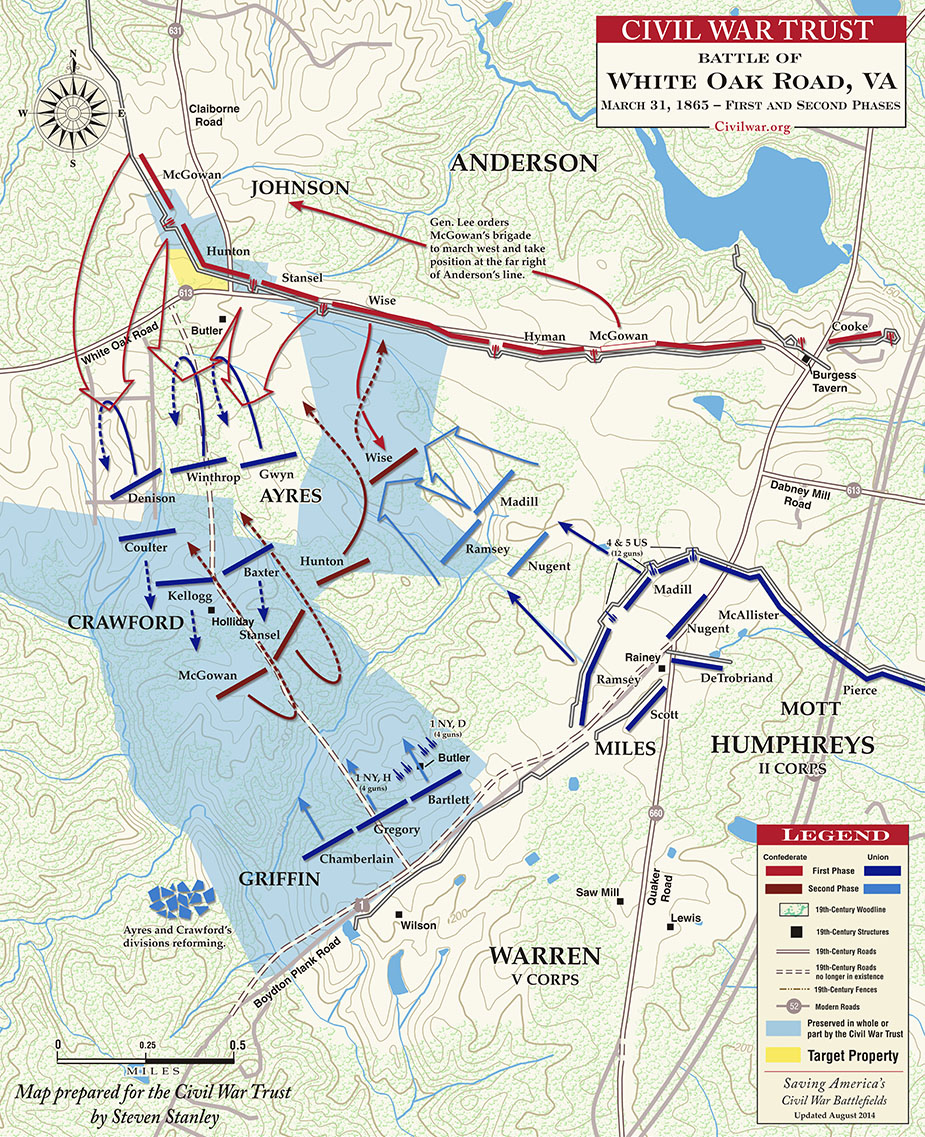

The Battle of White Oak Road, March 31, 1865

The initial Union movement during the final offensive against Petersburg had finally given Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant control of the Boydton Plank Road. With the South Side Railroad on his mind, Grant consolidated his position on March 31 and waited for weather conditions more agreeable for a movement. General Robert E. Lee meanwhile took advantage of the brief lull with a frantic attack to reclaim the initiative. Such was necessary to save Petersburg. After experiencing brief success below the White Oak Road that afternoon, the Confederate cause was further dampened by a determined Union counterattack that restored the front and sealed the fate of the Confederates at Five Forks, five miles to the west of the battlefield.

The initial Union movement during the final offensive against Petersburg had finally given Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant control of the Boydton Plank Road. With the South Side Railroad on his mind, Grant consolidated his position on March 31 and waited for weather conditions more agreeable for a movement. General Robert E. Lee meanwhile took advantage of the brief lull with a frantic attack to reclaim the initiative. Such was necessary to save Petersburg. After experiencing brief success below the White Oak Road that afternoon, the Confederate cause was further dampened by a determined Union counterattack that restored the front and sealed the fate of the Confederates at Five Forks, five miles to the west of the battlefield.

Having already issued orders for Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett to attack Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s Union cavalry moving up from Dinwiddie Court House, Lee decided early on the 31st to drive Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren away from the White Oak Road before the Union V Corps could comfortably settle themselves in among the swampy forests and connect with the cavalry to the southwest. Displaying his tendency for the offensive, Lee ordered four brigades out of their defensives positions to take advantage of the exposed Union left flank. If the Confederates rolled up the lead division of the V Corps, Lee could force the Union entirely back across Gravelly Run.

Brigadier General Samuel McGowan’s South Carolinians marched west of the Claiborne Road with orders to swing south and plunge into the flank of Warren’s lead division and drive them east while two more brigades pitched into their front. Brigadier General Henry A. Wise’s Virginians served to connect these three brigades to the established southern defenses near Burgess’s Mill filled by two North Carolina brigades borrowed from Heth’s Division. Major General Bushrod Rust Johnson took charge of these six brigades from three different corps in an awkward command structure.

McGowan reconnoitered Warren’s position and found a great opportunity to relieve the pressure felt on the White Oak Road. “The point from which we viewed them was the most favorable for attack,” commented a staff officer scouting past the Federal lines. “It was within two hundred yards of their line, and a dense body of woods completely covered our approach from the position now occupied by the brigade.”

As the Confederate strike force formed for the assault Warren independently decided that he wanted to seize the White Oak Road west of its intersection with the Claiborne Road. Warren ordered Brig. Gen. Romeyn B. Ayres to drive the Confederate skirmishers back into their main line. The division commander sent Winthrop’s brigade up toward the heavy woods along White Oak Road. One of his staff officers tracked their progress:

I sat on my horse between the two lines of reserves, watching him go forward steadily in painful silence. Not an enemy was to be seen, not a musket was fired, until the advancing troops were half across the field, when suddenly along the edge of the wood at other end there appeared a long blue line of smoke; two minutes later Winthrop’s brigade was coming back and the further end of the field appeared full of rebel flags.

Johnson’s two brigades on the White Oak Road had observed their pickets retreating and decided to immediately charge Winthrop’s advance before McGowan’s attack could commence. Their premature assault did succeed in driving the Union brigade back. “The boys in blue stood it for awhile, but finding that we were closing in for a hand-to-hand fight, they broke and ran, we at their heels yelling like devils, and burning powder for all we were worth,” remembered a Virginian.

Ayres focused all his attention on the two brigades to his front, inviting a perfect moment for the South Carolinians to slam into their distracted left flank. Johnson quickly ordered McGowan to join the fight. “Before many seconds we immediately struck the enemy and charged them, cheering as was our custom, and pouring a rapid volley into their ranks,” recalled Lieutenant James Caldwell. “The assailants, thus vigorously assiled, were smitten with dismay, and gave back rapidly, while we pressed on and drove them clear into open ground.”

Warren sent Crawford’s division in to stem the tide, but as the Union reinforcements moved forward they mixed in with the debris of Ayres’s retiring division. With their momentum brought to a halt, Crawford’s men did little more than provide additional targets for the elated attackers. “I have no idea that the brigade every killed more men… than it did this day,” claimed Caldwell. “Line after line fairly melted before them and dissolved into a heterogeneous mass of rabble.”

Soon Crawford’s line also broke and ran back to Gravelly Run. As he watched his colleague’s divisions stream into his lines, Griffin angrily swore, “The Fifth Corps is eternally damned.” Three southern brigades had successfully routed two Union divisions.

The Confederates hoped to drive the Fifth Corps back across the Boydton Plank Road but had no reserves to commit against Griffin’s fresh division. Furthermore, they found their opponent protected by Gravelly Run, “posted on a hill whose sides were tangled and precipitous, and between which and us opened a ravine of considerable depth and unsafe footing.” The Fifth Corps artillery stood poised west of the plank road to deliver a devastating fire should the Confederates seek to follow up their success.

Unwilling to risk further losses, McGowan called a halt while the cowering remnants of Ayres’s and Crawford’s division recuperated behind Griffin’s entrenched line. Meanwhile Warren pleaded with Humphreys to send assistance.

The Second Corps commander deployed Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles’s division to attack the White Oak Road line. He immediately ran into Wise’s Virginians just beginning their movement southward and pushed them back into their earthworks. This reversal isolated the three Confederate brigades to the west and forced them to return to Ayres’s original skirmish line south of the road around 3 P.M. Warren then turned to Griffin to spearhead an assault to reclaim their former position.

Brigadier General Joshua L. Chamberlain led led his men forward across Gravelly Run with Gregory’s brigade on his right and Bartlett’s brigade en echelon to his left. The rallied men of Ayres’s division supported Griffin’s left while Crawford connected the corps to Miles.

As the V Corps pressed forward, Sergeant Berry Benson poured a heavy barrage into the forward movement using the captured Spencer rifle gifted to him by his brother:

Our fire was so hot that before the enemy had advanced far, they stopped suddenly and lay down—all except a few officers whom we could see standing up, endeavoring to urge their troops forward. We could see them waving their swords over their heads, the blades flashing in the sunshine. I think there were three flags crowded together, right in the center of the group. The color bearers were lying down holding their flags upright. And how we did keep pouring the bullets into them, the flags for a mark! Presently, down fell a flag, the color bearer shot as he lay on the ground. Then up it rose again; down again; up again! The flags continued to tumble and rise, while the men lay still on the ground, the swords of the officers whirling and flashing as they tried to bring their men to a charge.

Under the South Carolina sharpshooters’ cover, the Confederate infantry attempted to quickly reverse Ayres’s former rifle pits before the rallied V Corps could close in on them. With every second counting, Hunton ordered his Virginians to hold their fire until the enemy got close. The first volley caused a portion of the Federal line to break and run but the majority reformed under fire and drove the Confederates back into their main line. “I thought it was one of the most gallant things I had ever seen,” confessed Hunton.

As McGowan’s brigade fell back a stray bullet struck Colonel Wick McCreary of the 1st South Carolina through the lungs. His men carried their commander behind the earthworks on a stretcher, where he soon expired. “It was distressingly sad that Col. McCreary, after so long and brilliant service, should fall in almost the last battle, even as the fabric of the Confederate power was tottering and being broken to pieces and the last blow being struck,” mourned a fellow regimental commander. “The smile that always lit up his pleasant face paled in death near the enemy.”

With the Confederates falling back, elements of Chamberlain’s men claimed a foothold on White Oak Road past Johnson’s right flank. Warren longed to further redeem his corps’ reputation with an assault against the Confederate line and moved forward with his skirmishers under artillery fire to scout the enemy’s earthworks. What he found quickly discouraged his hopes. “The enemy’s defenses were as complete and as well located as any I had ever been opposed to,” he reported and decided not to sacrifice any more of his men in a frontal charge.

By the end of the fighting the Union army suffered 177 killed, 1,134 wounded, and 554 missing on March 31, with Confederate losses likely total around 800. Unlisted among the casualty reports was a loss with significant consequences for Lee’s army. Warren’s seizure of the White Oak Road near its intersection with Claiborne Road in the aftermath of the battle now isolated Pickett’s Division four miles to the west who had done plenty of fighting of their own that day.

I am interested in two fights that are not on the map. First, the 13th NC of Scales’ brigade was attacked by II Corps units. Second, the sharpshooters from McGowans brigade had filled the line after the brigade left to attack the V Corps left flank. jThe sharpshooters were attacked and fought for several hours in what they described as a jungle. where did this happen?

I really want tro hear from Edward on this.