The Last Major Engagement of the War: The Fall of Fort Blakely

With the Fall of Spanish Fort on April 8, the lone defense of Mobile now fell upon Gen. St. John Liddell and his garrison of around 4,000 men at Fort Blakely, a series of fortifications around the small town of Blakely. As the siege of Spanish Fort had gone on, Liddell faced off against the column of troops that had moved overland from Pensacola to join Canby. This column was commanded by Gen. Frederick Steele and was composed largely of U.S.C.T. troops and began siege operations against Liddell.

Steele’s men had advanced north from Pensacola to Pollard, Alabama, then turned west and came down upon Blakely from the north as Canby and his forces moved up from the mouth of Mobile Bay from Fort Morgan, catching the Confederate defenders in a vice. Now with the escape of the Spanish Fort garrison, Canby moved his men north to join Steele at Blakely. Canby now concentrated around 13,000 men to face Liddell’s forces.

Canby was in no mood to continue the siege, with the escape the previous evening of Gibson and his men. He didn’t want to have a repeat, so ordered an assault for the afternoon of the 9th.

As Robert E. Lee surrendered his forces to U.S. Grant, Canby’s men, both white and black, prepared to storm the imposing works of Fort Blakely. The Confederate defenses were intimidating to say the least: strong earthen redoubts, countless rifle pits, seemingly unending lines of abatis, lines of knee-high telegraph wire, and torpedoes. All that would make the assault hazardous enough without the defenders—and those men were some of the best the Confederacy had left, the remains of the famed and feared Missouri Brigade commanded by Gen. Francis Cockrell. Along with them were the Mississippians of Gen. Claudius Sear’s Brigade and Gen. Bryan Thomas’ untried Alabama Reservists, plus several batteries of artillery.

As the last of Canby’s men arrived to complete the encirclement of Liddell, preparations were made for an all-out attack as the sun made its way westward over the Mobile Bay toward sunset.

However, fate had other things in mind.

Around 3 p.m., Gen. William Pile—commanding one of Steele’s U.S.C.T. brigades—ordered his men forward against the left of the Confederate defenses. “With a cheer they started forward over logs, brush, & fallen trees & soon drove the Rebs from their rifle pits & occupied them themselves,” an officer noted. “I sprang over our rifle pit & away we went on a hard run . . . . The Rebs saw us coming and swept the ground with shot, shell, & tried to stop our advance, but to no purpose. Onward, still onward we went, down a slope, across a ravine filled with logs, brush and stumps & trees, but these were hardly noticed. Then up a little rise. . . . O! My God how the Rebs did sweep that line with those searching devilish shells & it seemed that nothing could live under such a fire.”

The Mississippi and Alabama defenders howled as they saw the color of their attackers’ skin, and officers shouted, “Lay low and mow the ground—the damned Niggers are coming!” Some shouts of “No Quarter” were hard as they pinned down Pile’s men.

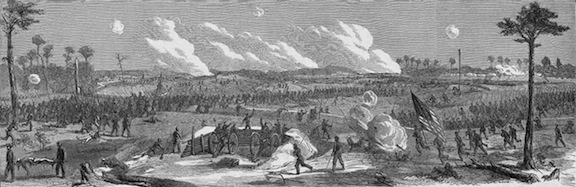

In their exposed forward position, the Federals held on. Receiving some reinforcements from other commands, they endured until 5:45 when the general assault began. All along the line, the command “Forward” was heard, and Canby’s blue coats rushed toward the Confederate lines belching forth fire and smoke.

Now the rest of Steele’s men joined Pile’s men for another rush toward the Confederate ramparts, many shouting, “Remember Fort Pillow!”

“We all rushed together for the rebel works,” Captain Henry Credenwise recalled, “& the old 73rd [Ed: Formerly New Orleans Native Guards], was the first to plant its flag upon that portion of the line captured by the colored troops.”

In the confusion and chaos that followed, the Mississippians now found the tables turned, and the prewar Southern nightmare of armed African Americans came to life. The negro troops rushed over our works, brandishing their guns in great rage” Artillery Captain Edward Tarrant recounted. “It looked as though we were to be butchered in cold blood . . . the officer of the negroes, however, succeed in getting control of them.”

Lieutenant Walter Chapman of the 51st U.S.C.T noted, “The colored troops did not take a prisoner, they killed all they took to a man.” However, others attested “no one was injured by any colored soldier after resistance had ceased.” An officer in the 73rd observed that the Confederates expected “No Quarter,” and “fell upon their knees expecting Ft. Pillow treatment but by the aid of their excellent discipline the troops were restrained. However the idea caused many of the Mississippians to flee down their collapsing lines toward the white union troops to surrender. “

As the Confederate left collapsed under Steele’s attack, the rest of Canby’s men rushed toward Cockrell’s Missourians and Thomas’s Alabamians. The Union tide was too much, and though blasted by torpedoes, tripped and cut by the razor-like telegraph wire, and stabbed by the broken abatiss, they finally gained the Confederate ramparts and overwhelmed the defenders after some brief but intense hand-to-hand fights. “It appeared to me that all hell had turned loose,” one Missourian, William Kavanaugh later wrote.

Captain Joseph Neal of the 1st-3rd Missouri Cavalry (dismounted) defended the imposing Redoubt No. 4. As Union troops rushed upon its ramparts yelling, “Torpedoes! Torpedoes!” Neal, a diehard to the end, shouted to his men, “No Quarter to the Damn Yankees!” Just then, a Union soldier shot him in the face, blowing most of his head off.

A brief but savage hand-to-hand fight now ensued in the interior of the redoubt. Sgt. W.R. Eddington of the 97th Illinois recalled: “We went over the ditch, over their breastworks and jumped down in the rifle pits right on top of them, too close to shoot them, too close to stick them with our bayonets, but we could still use the butts of our guns. We ordered them to throw their guns outside the breastworks. They did so and we gathered them up in groups and put guards around them until we could get things straightened out.”

The war now ended for the Missourians. Everything now fell apart. With flanks turned and the front overrun, the rear now became the front. As men surrendered, others fled only to find no escape. General Liddell later wrote, “Thus Blakely fell at the point of the bayonet. No flag was ever lowered.”

Unlike their comrades at Spanish Fort, the war ended the night of April 9 for most of the defenders of Fort Blakely, who now found themselves prisoners of war. The battle of Fort Blakely lasted only about 15 to 20 minutes, but it inflicted more than 3,500 casualties on both sides. Thus the final major engagement of the war ended.

Bad enough storming through shot and shell. But that 7th paragraph truly describes the horror of war.

I hope it was a typo, or perhaps the battle was one crappy affair.

Very well described. Easy to visualize the battle. Shows what great soldiers USCT were by the end of the war. I wish the author had continued with a narrative of what the victory meant to colored troops.

This is why I appreciate ECW, I had never heard of this battle before. And 7,000 casualties out of 17,000 engaged is shocking. But for such a sad, bloody war, I guess it was a fitting end.