The Last Confederate Fort and the Last Confederate General

Easter morning, April 16th, 1865, dawned unseasonably cool on the little town of West Point, Georgia, located on the east side of the Chattahoochee River and right on the Alabama state line. News of the assassination of President Lincoln and the surrender of Lee’s army were making their way like lightning through the land, but in West Point, there were other more pressing and immediate concerns.

Easter morning, April 16th, 1865, dawned unseasonably cool on the little town of West Point, Georgia, located on the east side of the Chattahoochee River and right on the Alabama state line. News of the assassination of President Lincoln and the surrender of Lee’s army were making their way like lightning through the land, but in West Point, there were other more pressing and immediate concerns.

The town was bustling with activity, though: the rail lines that made their way into the town to cross the river there were choked with a bottleneck of traffic that filled all four of the side tracks with freight cars and a train a quarter of a mile long stood still along the main track. The wagon bridge was also full of fleeing vehicles, carrying both military stores and civilian property. Union Raiders, part of General James Wilson’s Union Cavalry Corps, was headed their way.

Wilson’s men crossed the Tennessee River on March 22nd with the goal of destroying what remained of the Confederacy’s military industrial complex. Wilson destroyed iron works in central Alabama and then destroyed the Selma Arsenal while giving Bedford Forrest his last battle and defeat there on April 2nd. Wilson then rode east, capturing the former Confederate capital at Montgomery on April 12th. Now Wilson was aiming for Georgia.

Nature presented a barrier, though: the Chattahoochee River. Two options were available: the bridges at Columbus and at West Point, 35 miles to the North.

Wilson decided to lead the bulk of his command directly toward the manufacturing center of Columbus and send one brigade, that of Colonel Oscar LaGrange, to seize the crossings at West Point in case he found the defenses at Columbus to be too strong.

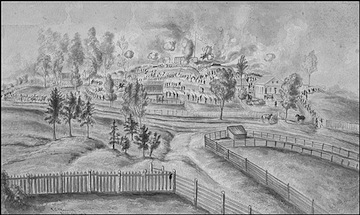

The news of the fall of Montgomery and the Union advance had set a panic into West Point, and the option for the post commander there, General Robert C. Tyler, looked grim. The town had a line of trenches around it, and a redoubt sporting three cannon—known as Fort Tyler in the General’s honor—dominated the town from the North West side. Fort Tyler was approximately 30 yards square, with walls four feet high, eight feet thick and fronted by a ditch ten feet deep and a line of thick abatis. A palisade was constructed to cover the southern entrance to the fort, but there were no head logs to protect the defenders, and this would prove fatal for many of its defenders. Despite its position and armament, the fort was dubbed “a slaughter pen” by one Confederate officer.

To man his defenses, Tyler didn’t have much, approximately 120 men consisting of solders on their way to their commands in North Carolina, refugees from Selma, hospital patients, and the local home guard—forces described by one participant as “a promiscuous and most voluntary gathering.” This force would have to face more than 3,000 veteran cavalrymen of LaGrange’s command. Despite the odds Tyler chose to fight.

LaGrange’s command approached the town around 10 a.m. and began to skirmish with Tyler’s outposts, pushing them back through the town, fighting from building to building, as the 18th Indiana Battery deployed and opened fire on Fort Tyler, pounding the earthen ramparts. As the Indianan’s guns roared, LaGrange’s troopers moved toward the fort. LaGrange ordered three of his regiments, the 1st Wisconsin, 7th Kentucky, and 2nd Indiana to dismount and engage the fort’s defenders; meanwhile, the 4th Indiana remained mounted and would, at the right moment, charge under the fort’s guns and capture the wagon bridge before it could be destroyed.

By mid afternoon, the time was right and the 4th charged, taking the bridge as their dismounted brethren occupied nearby buildings or took whatever cover they could and began a sharpshooting contest with the fort’s defenders. Among the first to fall under this leaden hail was General Tyler. Shot three times, he fell near the fort’s entrance—the last Confederate general to die in the war.

As the sun began to set, LaGrange decided the time had come to capture the fort, and he ordered his men to charge. One Wisconsin officer later described it:

Our boys are rapidly approaching the works. There they go into the ditch; now up on the embankment! There they lie within 10 feet of the enemy, waiting for the rest of the brigade to get up close as they are. While in the ditch lighted fuse shells are thrown over among our boys, but they prove boomerangs in every instance, for our boys pitch them back into the fort, where they explode . . . then they threw over great rocks. . . . The Bugler is sounding the charge. Up they spring to the top of the embankment like a swarm of bees. Up goes the white flag, they have surrendered!

Thus Fort and General Tyler fell—the last fort and the last general to fall in the war.

LaGrange had his crossing even as Wilson made his at Columbus.

Can you tell me the source of the block quote at the end of the article by the Wisconsin officer?