The Curmudgeon, The Eccentric, and the “Norse God”: How Three Men Impacted the Battle of Gettysburg: Conclusion

What to do? What to do?

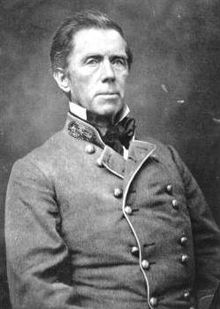

Even after all that had been thrown at him Dick Ewell determined he could make the attack, but he wanted support from Hill’s Third Corps. He sent Smith back to Lee with his request, then he ordered Early and Rodes to get into position. Ewell sent word to Lee “that they could go forward and take Cemetery Hill if they were supported on their right [by Hill].”

It did not take long for Smith to return with word from Lee that Hill had no men to lend in support of the attack. Hill had committed two of his three divisions to battle; his third and final division was too far away to lend support, as were all three of James Longstreet’s divisions, thus Ewell was on his own.

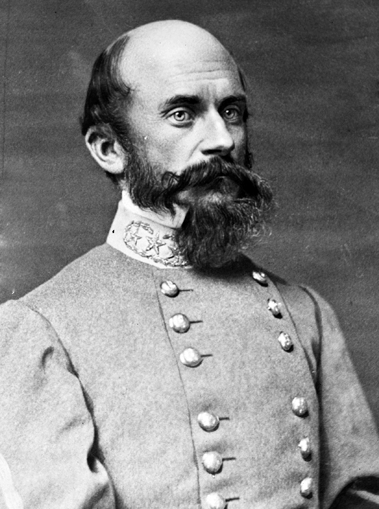

Dick Ewell quickly assessed the situation. Rodes division had sustained nearly 2,500 casualties in its fight along Oak Hill and Oak Ridge, the division was simply played out for the day.

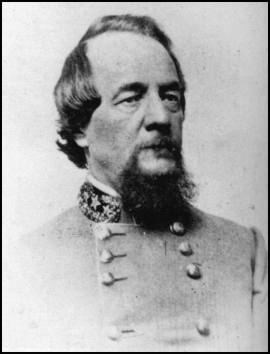

Jubal Early’s division had had a much easier go on the field. Early’s men had sustained less than 500 casualties in the fight with the 11th Corps. While many of Early’s men were still clearing the town of stray Federals, they were in excellent spirits and close at hand to make the assault, but were substantially weakened when Gordon and Smith’s brigades were called to Benner’s Hill.

Ewell did have one final division, which would have helped tip the scales in favor of the Confederacy. His third and final division commanded by Edward “Allegheny” Johnson was ordered by Ewell, prior to the outset of battle, to take the corps supply trains on a circuitous march, where they would link with the main body of the army along the Chambersburg Pike. The Pike was as badly bottle-necked as I-95 on Memorial Day weekend. Johnson and his men had taken to the unfinished railroad cut in hopes of reaching the field, yet they still were not at the front.

Lieutenant Thomas T. Turner of Ewell’s staff and volunteer aide/nephew of Jubal Early, Robert Early performed a reconnaissance of the field. The two young men discovered that Culp’s Hill sat unoccupied a quarter of a mile to the southeast of Cemetery Hill (though the two men somehow missed the Iron Brigade atop and adjacent to the northwestern side of Culp’s Hill). Ewell believed that if his men could occupy Culp’s Hill, the Union position on Cemetery Hill would be untenable. The corps commander now set his sights on the new prize.

Riding into town Ewell found Jubal Early and Ed Johnson arriving with the lead elements of his division. Ewell suggested to Early that his men occupy Culp’s Hill immediately. The normally aggressive division commander balked at the idea, telling Ewell that Johnson’s men should occupy since his division (Early’s) had done the bulk of the hard marching and fighting for the day, which was a wholly unfair assertion. Johnson traded sharp words with Early, but Ewell took Early’s side.

Near dusk, Johnson’s men slowly filtered out of the eastern side of town. Unbeknownst to the southerners, Federals had already occupied the hill. Colonel Ira Grover marched his 7th Indiana to the summit of the hill. The 420 or so Hoosiers were the only Federal force atop the hill proper. Grover pressed forward Company B of the 7th as skirmishers.

The majority of 30-man squad from the 25th Virginia, sent by Johnson to reconnoiter, wound up as Union prisoners. Johnson, whose orders were to take the hill if it were unoccupied, perused the prize no more. The chance to take the ground without a fight slipped away. Over the next two days, assaults on Culp’s Hill would lead to some 2,500 Confederate casualties during the longest-sustained combat on the battlefield.

Later that night Lee arrived on the east side of town and had his first face to face meeting with Ewell since the opening of the Gettysburg Campaign. Lee spoke with Ewell, Rodes, and Early about the situation on the east side of town. According to Early, he did most of the talking. The long and short of the conversation boiled down to two topics. The first topic was if the Second Corps could, “…attack on this flank at daylight to-morrow?” The cadre of officers shouted down this idea. The second topic was if “I [Lee] had better draw you around towards my right, as the line will be very long and thin if you remain here…” Again, this idea was shouted down, which would come back to haunt Lee in the long run, which is a story for another time.

*****

In essence Richard Ewell was in a no win scenario on July 1st. With no support from Lee, Longstreet, or Hill; Dick Ewell was expected to take a highly defensible hill, with poor avenues of advance, and even worse positions for his artillery.

Ewell also had to deal with unclear orders from Lee. In his official report, Lee stated, “General Ewell was, therefore, instructed to carry the hill occupied by the enemy [Cemetery Hill], if he found it practicable….” It’s important to note that those words—“if practicable”—never appeared in print until Lee filed his revised report of the battle in January 1864, more than six months after the fight.

Lee went on to say; “Without information as to its proximity, the strong position which the enemy had assumed could not be attacked without danger of exposing the four divisions present, already weakened and exhausted by a long and bloody struggle, to overwhelming numbers of fresh troops. General Ewell was, therefore, instructed to carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army, which were to hasten forward.” Unfortunately, in the years since the battle, much emphasis has been placed on the phrase “if practicable”—words that Lee may have never uttered in the heat of battle—and the warning about avoiding a general engagement has been ignored.

Lee expected Ewell to take a hill, which hid two major roads leading to the town, the Taneytown Road and Baltimore Pike. Without knowledge of what could be coming up those roads the Confederate army was blind. The entire Army of the Potomac could have been massing behind those hills, which we know is untrue in hindsight, but in the heat of battle the combatants had no idea.

Then there was the fact that Lee wanted to “avoid a general engagement…” By 5 PM on July 1st, Lee should have been fully aware that he and his army were in a pitched battle, there was no avoiding a general engagement, the pot was already boiling over.

Unfair accusations came at Ewell thick and fast from the men who served under him in the campaign.

Jubal Early had a vested interest in blaming Ewell for the lack of action on the afternoon and evening of July 1. Ewell had supported Early’s decision not to move his division to Culp’s Hill, and that decision had catastrophic consequences for the Army of Northern Virginia.

After the war, Early contended that he had vigorously supported an assault on Cemetery Hill, yet on the evening of the battle he claimed his men were too tired and disorganized to occupy unoccupied Culp’s Hill. If his men were in no condition to move unopposed to an empty hilltop, how could they have led an attack against a heavily fortified enemy position? “The discovery that this lost us the battle,” Campbell Brown said, “is one of those frequently-recurring but tardy strokes of military genius of which one hears long after the minute circumstances that rendered them at the time impracticable, are forgotten—at least I heard nothing of it for months & months, & it was several years before any claim was put in by Early or his friends that his advice had been in favor of an attack & had been neglected.”

In fact, Early led a vigorous campaign—after Lee’s death, so that Lee could not refute any of Early’s claims—to place blame for the loss at Gettysburg on Ewell and, for his actions on July 2 and 3, on First Corps Commander James Longstreet. Trimble, cavalryman Fitzhugh Lee and others joined in. That scapegoating has since become accepted as a central tenet to the “Lost Cause” mythology. But tactically Ewell did the right thing on the evening of July 1. His decision not to assault Cemetery Hill was a sound military judgment based on the evidence he had at the time weighed against discretionary orders from his commander. Critics have second-guessed Ewell’s judgment about the “practicability” of an assault, ignoring the fact that Lee expressly forbade him from bringing on a general engagement. Early had his own wartime failures to make up for and blaming others for his own shortcomings was a game he started as early as May 1863.

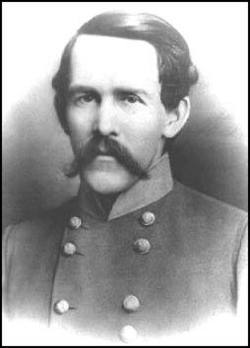

Major General Isaac Trimble, who was attached on special duty to Ewell’s command during the battle, was among those who tried to dismiss Lee’s warning. Writing for the Southern Historical Society (SHS) years after both Lee and Ewell had died, Trimble recalled his attempt to persuade Ewell to attack. As Trimble recalled, Ewell called attention to Lee’s order not to bring on a general engagement. “[T]hat hardly applies to things,” Trimble responded, “as we have fought a hard battle already, and should secure the advantage gained.”

In Trimble’s version, he urged Ewell to take not Cemetery Hill, where the Union army was trying to re-form, but Culp’s Hill. “General, there is an eminence of commanding position, and not now occupied, as it ought to be by us or the enemy soon. I advise you to send a brigade and hold it if we are to remain here,” Trimble said, adding, “it ought to be held by us at once.” Ewell replied, “When I need advice from a junior officer, I generally ask it.”

Trimble never forgot the insult. Recounting his experience in the SHS papers, Trimble made an effort to paint Ewell as being “far from composure” and “under much embarrassment” and said Ewell “moved about uneasily, a good deal excited” and “undecided what to do next.”

“[F]ailure to follow up vigorously on our success…was the first fatal error committed,” Trimble wrote. “It seemed to me that General Ewell was in a position to do so. But he evidently did not feel that he should take so responsible a step without orders from General Lee….”

Trimble’s bloviations are akin to a scorned ex-wife. The truth of the matter was that Trimble was not in the combat leadership role he craved. The 61 year old Trimble had been wounded, like Dick Ewell, at Groveton. He had been shelved from August of 1862, to the opening of the Gettysburg Campaign. On May 7th, 1863, the day after the Chancellorsville Campaign closed, Lee wrote to President Jefferson Davis “Genl Johnson will command Trimbles {sic}Division, Genl Trimble is still disabled and I fear will not be able to take the field.”

By the time the army had begun its march towards Pennsylvania Edward Johnson was in command of Trimble’s men and Trimble was an irritable know-it-all without a combat role. Trimble invited himself to join Lee’s headquarters on the way north. Lee wisely pushed Trimble off of Ewell, who had endured the unsolicited advice from his unwanted subordinate for days.

According to Lieutenant Randolph McKim, Trimble ranted to Ewell over the taking of Culp’s Hill by saying “Trimble was most urgent, ‘Give me a division’ said he, ‘and I will engage to take that hill.’ When this was declined he said. ‘Give me a brigade and I will do it.’ When this, too, was declined the gallant Trimble threw down his sword and left General Ewell’s headquarters, saying that he would no longer serve under such an officer!’” (The irony was Trimble was not serving under Ewell, he was an unwanted camp follower!)

Today this has been made famous by the movie Gettysburg. Nowhere in Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels (or the related film Gettysburg), which covers Trimble’s encounter with Ewell, does Ewell get to tell his side of the story, so modern audiences typically accept Trimble’s version as truth.

And of course there was the fact that Richard Ewell was living in the shadow of Stonewall Jackson. Old Jack had not been cold in the ground for two months as of the Battle of Gettysburg, yet one would have thought he rode into Pennsylvania beside his successor.

Jackson earned a reputation for aggressiveness and independence; if ordered to do something, Jackson did it, there was no gray area with Stonewall. It is a small leap, then, to assume that he would have found it practicable to take Cemetery Hill. “Oh, for the presence and inspiration of Old Jack for just one hour!” lamented Jackson’s former chief of staff, Major Alexander “Sandie” Pendleton, who went on to serve under Ewell and future Second Corps commander Jubal Early.

There is a major flaw behind that assumption, however. “It is a fact not generally known…that in all his famous flank movements Gen. Jackson was careful to examine the ground to learn the exact position of the enemy,” wrote Southern war correspondent Peter Wellington Alexander, “and hence his blows were always well aimed and terrible in effect.”

Jackson had learned a hard lesson at the Battle of Kernstown in March 1862, when faulty intelligence about the enemy’s position led to his only battlefield defeat. Thereafter he made an effort to discern his opponent’s dispositions. In fact, it was in the midst of one such attempt at gathering information that Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men at Chancellorsville. To assume he would have stormed Cemetery Hill without any idea of what lay beyond it places too much emphasis on Jackson’s aggressiveness at the expense of his good sense as a tactician.

A closer examination of the way Jackson handled his corps in the hours before his famed wounding at Chancellorsville is essentially a mirror to the actions of Ewell on July 1st at Gettysburg.

Jackson, like Ewell, had just driven the Federal 11th Corps from the field. He too had engaged two of his three divisions at hand and both divisions had lost cohesion. The two commanders both had listened to the concerns of their division commanders and called upon fresh reserves to execute the next phase of action, while at the same time tried to gain a clear understanding of what enemy forces lay ahead. Finally, the two men had not just haphazardly run headlong into the waiting teeth of Federal artillery. While Richard Ewell is decidedly not Stonewall Jackson, the actions of Dick Ewell and Stonewall Jackson mirrored one another on their most famous and trying days of the American Civil War.

At the end of the day Richard Ewell will remain the scapegoat of many armchair generals. Sadly for his legacy he did not take Cemetery Hill and failed to secure Culp’s Hill in the process. While the blame for these non-actions weigh heavily on his shoulders one must consider that Robert Rodes disjointed assaults and long casualty list, coupled with Jubal Early’s standoffish attitude on July 1st, and not bringing Johnson’s division along with the rest of the corps all created the perfect set of circumstances for the Federal army to hold the heights south of Gettysburg, and to doom the reputation of one southern officer forever more.

Enjoyable reading- thank you !

Great job of “peeling the onion”…too much of accepted history of this event is over-simplified; this series of articles reveals the complexity Confederate officers faced at this critical moment and makes it understandable. Well done!

I never knew that guy was trimble in the movie