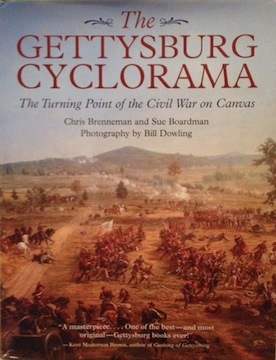

Review: The Gettysburg Cyclorama

Having worked so much at the Wilderness, I don’t buy into that whole “Gettysburg as the turning point of the Civil War” nonsense. Aside from that premise, though, there’s little negative to say about Chris Brenneman and Sue Boardman’s stunning new book The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas.

Having worked so much at the Wilderness, I don’t buy into that whole “Gettysburg as the turning point of the Civil War” nonsense. Aside from that premise, though, there’s little negative to say about Chris Brenneman and Sue Boardman’s stunning new book The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas.

Published by Savas Beatie, LLC, as an over-sized 8.5 x 11 hardcover, this book is a full-color Cadillac: more than 400 photos printed on glossy paper, accompanied by detailed text, exploring a fascinating subject. The book is as handsome as it is interesting.

Brenneman and Boardman—along with photographer Bill Dowling—are Licensed Battlefield Guides at Gettysburg. Brenneman works for the Gettysburg Foundation and Boardman was involved with the Cyclorama’s restoration in the mid-2000s. She also wrote one of only two other studies on the Cyclorama, so the new book serves as a substantial update. Their prose reads with the clean clarity of a high school textbook, which lets the painting and its stories be the star.

Few Civil War objects are as iconic as Gettysburg’s Cyclorama. At nearly fifty feet high and 400 feet around—weighing nearly six tons—it’s one of the most substantial works of Civil War art in existence. Beyond its role as art, though, the authors point out that the painting also serves as an important piece of documentation. “For the most part,” they explain, “Civil War cycloramas provided well-documented visual history for those who viewed them.”

That’s particularly true of the Gettysburg Cyclorama, which was the second of four that European artist Paul Phillippoteaux created. After his first version, exhibited in Chicago starting in 1883, veterans offered their recollections of the battle and additional information came to light, allowing Philippoteaux to revise and refine his work in subsequent iterations.

The book rolls out with a chapter on cyclorama basics: creating drafts, preparing the canvas, transferring the image, painting the scene, and transporting the final product. “The process, when completed,” they authors say, “provided both an artistic and a technical presentation which allowed viewers to enjoy an immersive experience that placed them, through a multi-dimensional illusion, into the environment depicted on the canvas around them.”

The second chapter traces the history of cycloramas in America, including Philippoteaux’s four Gettysburg paintings. “The phenomenal success of the Gettysburg cycloramas inspired the creation of some three dozen Civil War battle paintings over the next decade,” the authors write. (The most famous of these other Civil War cycloramas is undoubtedly the siege of Atlanta at the Atlanta Cyclorama Center.)

While the Cyclorama depicts history, as an object, it has a fascinating history of its own, which Brenneman and Boardman trace in detail, never bogging down in awful minutia while still offering a bajillion interesting tibits.

In fact, chapter three of the book specifically focuses on “tidbits,” but that seems an injustice to the rest of the book, which is just as chock-full of anecdotes, facts, and stories.

As an example, the book traces the story of Meade’s headquarters in the painting. Absent in the Chicago cyclorama because it wasn’t visible to Philippoteaux when he observed the battlefield, patron Charles Willoughby urged the artist to add it. As a landmark, it was too well known by veterans to omit it from the scene. Philippoteaux added it to the three subsequent paintings. “While the resulting white building in the painting is fairly accurate in size and shape, it is located too far forward on Cemetery Ridge and faces west instead of south,” the authors explain. Then they add the kind of button that dresses up the manuscript throughout: “Also, the original farmhouse was wood, not stucco as it appears in the painting.”

Chapters four and five cover changes made to the painting over the years the key to painting, which offered notes to visitors about what they were looking at. Keys varied from version to version and, when they went on display, from city to city to highlight items that might be of particular interest to the locals. Such shifting documentation made researching the book particularly challenging, the authors admit.

The heart of the book, running from pages 75-215, are sections that break the painting down into ten distinct frames and then offer notes about those views. The notes are exhaustive but not overwhelming, covering the history of the battle, the history of the painting, and the relationship between the two. It’s a Gettysburg buff’s dream. The careful photography by Dowling supplements the work of the authors superbly, giving readers clear points of reference.

“Keep in mind that we were analyzing a work of art,” the authors caution, “and some of our determinations may be subjective and open to interpretation. In areas where there were several possible interpretations, we tried to give multiple options.”

This is an especially important caveat, something I make particular note of because of the tendency of so many people to conflate works of art with works of history. The Cyclorama was intended to be both, first and foremost by entertaining crowds so that Willoughby and other investors could make their money back. Importantly, though, the painting entertained because it was so detailed and realistic.

Still, the pitfalls of any art-as-history remain, even for a work as monumental as the Cyclorama. Brenneman and Boardman navigate those waters expertly.

In the end, The Gettysburg Cyclorama is a treat to pour over.

The Cyclorama has long been an interest of mine, and I am glad to see it gets its due. It was conspicuously absent at the exhibit of Civil War art in New York, btw. Huzzah!

Dear Chris M.,

Thank you so much for the wonderful review of our new book. We really spent a lot of time on the book, it is really great to hear that other Civil War experts like it. Thanks again—Chris Brenneman