“They Fought Because They Would Not Be Slaves”

![]() Revolutionary War Wednesday and Emerging Revolutionary War is pleased to welcome guest historian Mark Maloy this week.

Revolutionary War Wednesday and Emerging Revolutionary War is pleased to welcome guest historian Mark Maloy this week.

African-Americans fought for the Americans during the Revolutionary War, right? Many of us remember learning about Crispus Attucks dying during the Boston Massacre or have heard the oft-repeated saying that the Continental Army was the last integrated American army until the Korean War.

Even where I work at the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in DC, the introductory film mentions that “Americans, black and white, had fought and won a glorious revolution” (click here for link).

On the National Mall, plans are in place to erect a monument for black patriots in the Revolution (click here for link).

The stories about African-American participation in the Revolution are not a new subject. In fact in the 1850s as the Civil War was about to break out, many people, black and white, North and South were looking at this very subject and debating what happened and why it mattered.

During the Revolution about 5,000 African-American men, free and slave, fought in the Revolution on the Patriot side. However, it is estimated that tens of thousands of slaves fled plantations to the British side. Of these some fought in the army, including a unit that was formed called the “Ethiopian Regiment”. Most served the Crown as laborers and teamsters. Unfortunately, many slaves who ran to British lines often died of disease or ended up back in slavery. Some made it to freedom, but often in a strange new place like Nova Scotia or Sierra Leone.

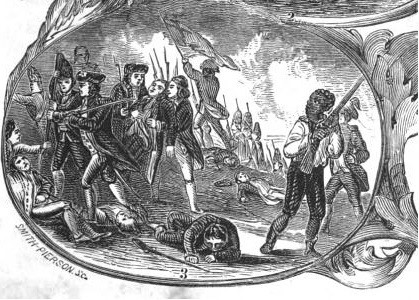

This image is from William C. Nell’s book The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855). Notice how the white master was removed and the focus is not on General Warren, but the African-American holding his musket.

As the abolitionist movement went into full swing in the mid-1850s, an African-American abolitionist named William C. Nell published a book entitled Colored Patriots in the Revolution that detailed the service of dozens of blacks who fought during the war. However, it focused exclusively on the stories of those who chose the patriot side, while the stories of the tens of thousands who chose the other side were dismissed as having been “carried off” or being “induced” by the evil British. Nell’s goal was to show that African-Americans had been loyal to the United States and to the cause of liberty. Because of this loyalty, they had earned and deserved equality and justice.

Pro-slavery advocates, on the other hand, actually did not discount Nell’s writings. While they remained much more silent on the issue at large, they did not discount these tales of black patriots and often related their own stories. In these stories though, found in newspaper articles and pamphlets in the South, slaves were loyal to their masters, and their actions helped secure a nation in which slavery existed and in which they were content to remain slaves. The image of blacks fighting with muskets in their hands was tempered by the fact that they believed blacks only made good soldiers under the watchful eye of their masters. All of this supported a paternalistic view of slavery.

Ultimately, both abolitionists and slaveholders were trying to use the stories of black patriots in the past to reinforce and further their contemporary agendas. Both sides, however, were interestingly ignoring the fact that during the Revolution most slaves were not necessarily interested in being loyal to their country or their master, but went where personal liberty would most likely be attained.

The Civil War eventually erupted in 1861 and once again slaves would have to make choices on which side to take. Once again they would often go where they believed personal liberty and freedom could be attained.

Mark Maloy is currently a ranger and historian with the National Park Service at Frederick Douglass National Historic Site located in Washington D.C.

“’They were good soldiers.’: African–Americans Serving in the Continental Army,”

http://www.scribd.com/doc/123231213/%E2%80%9CThey-were-good-soldiers-African%E2%80%93Americans-Serving-in-the-Continental-Army