Do You Know George Wythe?

Down the street from the Governor’s Palace in Colonial Williamsburg sits a two-story brick structure. Living historians, in first-person, debate the road to the American Revolution.

But, who was George Wythe?

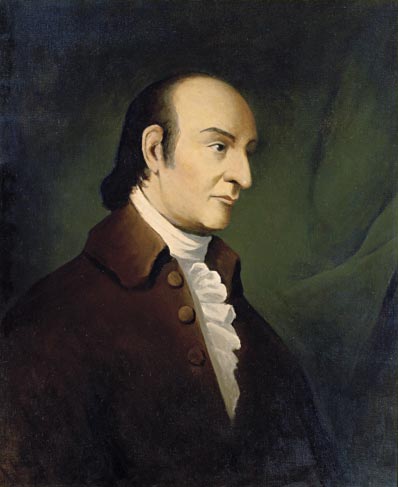

(courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg)

According to Thomas Jefferson, “no man left behind him a character more venerated than George Wythe.”

He ruled later that Virginia’s Declaration of Rights included African-Americans when the document stipulated that “all men” are born free. All, including African-Americans should “be considered free until proven otherwise.”

Unfortunately, Wythe’s ruling did not survive the legal debates that ensued.

Yet, the mere fact that Wythe was in a position to challenge the doctrine of slavery in Virginia spoke of the position he had attained during his life.

Born in 1726 in Chesterville (now Hampton) into the planter class, the young Wythe lost his father while still in infancy. However, his mother, Margaret Walker Wythe installed in her young child the thrill and love of learning.

Wythe would carry that message with him the rest of his life.

In 1746 at the age of 20, he was admitted to the Colony of Virginia’s General Court Bar in nearby Elizabeth City County. The following year he married his law partner’s daughter, Ann Lewis.

However, 1748, would be a year of professional success for Wythe when he was admitted to the York County, Virginia bar but personally would be one of devastation. His wife Ann died that same year on August 8th.

His second marriage to Elizabeth Taliaferro in 1754 would eventually yield the house in Williamsburg now known as the George Wythe house.

As Wythe continued to progress in the law career he became a mentor and teacher to some of the more well-known prominent Virginians of the Revolutionary Era. Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall both studied law under Wythe in Williamsburg.

In Philadelphia in 1776, when the time arose to sign the Declaration of Independence, a blank spot was left at the top of the Virginia signer’s section.

The spot was reserved for George Wythe who was absent the day the Virginia delegates signed the document.

He was held in that high esteem by his fellow Virginians.

Later accomplishments included helping to draft the seal for the state of Virginia, as he was one of two that worked on that committee.

Unfortunately, Wythe had a tragic death, being poisoned by his grandnephew by eating poison strawberries or drinking poison coffee–not sure which but both have been accepted as the possible conduit of poison. George Wythe Sweeney, the grandnephew had forged checks against Wythe’s account to help offset his debts. He was also upset that a former slave, including Michael Brown, who was freed, was also named in Wythe’s will.

Brown was also poisoned and died a few days later. Wythe lingered for a fortnight and actually was told about his grandnephew’s evil deed in time to change his will.

Wythe died on June 8, 1806 and is buried at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia.

Sweeney was indicted for murder but no witnesses were found and the jury concluded that the only evidence was circumstantial. The only person that may have witnessed Sweeney discarding the poison vial into the kitchen fire was freed African-American Lydia Broadnax, one of Wythe’s former slaves. Unfortunately, she was not allowed to testify because of her skin color which would have brought chagrin to the late Wythe.

But, the question remains, is it not time that you learn who George Wythe was?

A trip to Colonial Williamsburg is a great way to start!

(courtesy of Waymarking.com)