Saved by His Pocket Diary: Sergeant Francis McMillen at the Jones Farm

In a small leather bound journal, Francis McMillen daily jotted down notes while hunkered down in the Petersburg trenches during the last year of the war. He mixed frequent updates on the weather with sarcastic commentary on the boring routine of everyday soldier life as he spent the winter months filing reports and worked on his quarters. When reading his musings, one can tell that McMillen was not the ideal, professional soldier during this time, but I can’t help but appreciate his honest opinion of his own service in the army.

McMillen’s diary entries begin on January 1, 1865, a month in which he appears to be detailed in assisting the quartermaster. The dull routine upset the sergeant.

“The world at large will have to be content with all quiet in the Potomac Army,” he dryly noted on January 4th. His impatience with inactivity appeared again eleven days later with the observation: “If a citizen was to arrive here in the night & was not informed that he was in the Army he would not know that he was.”

McMillen applied for a furlough at the end of the month but was disgusted that his captain kept the paper in his tent and would not bother to approve it and forward it along. Finally he received a rejection at the end of January along with orders summoning him back to his regiment. “That part I did not care for,” he noted.

Lieutenant Colonel Otho H. Binkley greeted him back to the 110th Ohio Infantry with an assignment in the adjutant’s office. McMillen began his clerkship by making out the monthly returns “which is a very tedious job” as he was not “used to sitting so long, it makes me quite tired.”

The February 5-7 engagement at Hatcher’s Run passed without impact on Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour’s division of the VI Corps, to which McMillen and his Ohio comrades belonged. And so he spent the rest of the month hoping for good news from Sherman’s army operating to the south. McMillen also briefly served as sergeant of the guard for the first time in two years, the responsibilities of which, he admitted, “I hardly know how to perform.”

The beginning of March brought an assignment to the picket line, but the Ohioans found they hardly had to worry about the safety of their camp. Instead, during their brief stint in the rifle pits, the pickets gathered up a half a dozen Confederate deserters that came in with “about the same old tales to tell… they say their men are going home as fast if not faster than they are deserting to us.” Coupled with good news from Sherman and Sheridan, McMillen excitedly looked forward to the end of the war.

During the middle of the month he assisted with the packing up and sending away of all surplus baggage, a sign which foretold the resumption of active campaigning in the near future. McMillen commented on the 15th that he was “now ready but not altogether willing for the word fall in.” Buoyed with a little more confidence the next day, he wrote: “Let the word come when it may. We will start out with the determination of killing or capturing all that attempts to oppose us.”

Operations resumed ahead of schedule on March 25, when the VI Corps was aroused early by the roar of gunfire on the IX Corps’ front east of the city. Major General John Brown Gordon had scraped together half the Confederate infantry for a desperate assault on Fort Stedman, hoping to sever the U.S. Military Railroad which lay behind, but by the middle of the morning Maj. Gen. John Grubb Parke’s bluecoats had easily kicked the Confederate infantry out of their gained position. Major General George Gordon Meade now wanted his divisions on the western side of Petersburg to exploit the Confederates’ reduced numbers in their front.

Originally optimistic about the operation, Major General Horatio Gouverneur Wright, commanding the VI Corps, dragged his feet in ordering his men forward. He finally shook out a line of three regiments–Lt. Col. George B. Damon’s 10th Vermont, Lt. Col. Charles M. Cornyn’s 122nd Ohio, and Binkley’s 110th Ohio–to charge northwest from Fort Welch and seize the Confederate rifle pits located on the Jones Farm.

Binkley reported that he “ordered the two [Ohio] regiments forward on the double-quick with bayonets fixed, and would have carried the enemy’s line, which was strongly fortified, but when he had gotten within about 150 yards of the works the shortness of our line exposed us to a severe flank fire.”

Despite his clerical work, Sergeant McMillen participated in this movement. The 25th of March happened to be his thirty-third birthday.

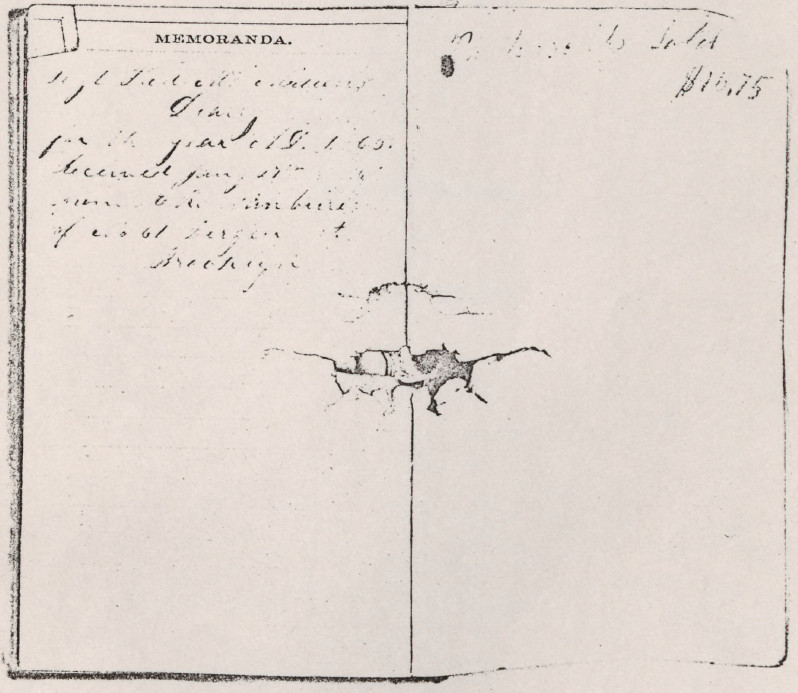

As he charged forward alongside his fellow Buckeyes, McMillen fell with a sharp blow to his chest. The dazed soldier likely gathered his composure on the ground and surveyed his personal effects with relief. He pulled his diary out of his coat pocket and saw the clear impression of a spent minie ball that crushed the back half of the journal. The bullet had deflected away from his chest, bounced off his pocket watch, and then slammed into his belt buckle before falling harmlessly to the ground.

“This book was in my breast pocket and received the ball which was intended to take my life,” he jotted forty-five years later for a previously unwritten entry for March 25, 1865, “but thanks to the book, watch, and beltplate I am still alive.”

After the repulse of his weak offering of three regiments, Wright ordered a second assault and committed two full infantry divisions. The Federals captured the Confederate picket line, setting the stage for their dramatic charge eight days later.

McMillen wrote no more diary entries during the war. Though I would love to read his opinion on the April 2nd Breakthrough at Petersburg, I can’t blame him for not writing anymore. I would not have taken the protective book out of my pocket until I was safe back at home.

And though he seemingly did not thrive during the monotony of camp life, Sergeant McMillen did make his impact on the battlefield on April 2, 1865. His brigade charged up the middle branch of Arthur’s Swamp that morning and burst through the earthworks held by Col. William Joseph Martin’s 11th, Lt. Col. Eric Erson’s 52nd, and Capt. Thomas James Linebarger’s 28th North Carolina regiments.

The Confederates had placed multiple layers of abatis in front of their entrenchments to stall an assault, but the small openings they left for pickets to venture in and out from proved to be their demise. Within minutes of coming under fire, the two brigades of Seymour’s division had penetrated the southern lines near Mary Hart’s house.

“The guns on the right opened vigorously on the advancing column, which was about daylight, but the overshot the men charging in front,” recalled an injured onlooker in McMillen’s regiment. “I could plainly see the rebel works and abatis when the column first came up, the men were scattering and they were kept back, but some of them went through the gaps that the Johnnies left by which to get out to their rifle-pits.”

The triumphant Federals then swarmed through the marsh past the lower branch of Arthur’s Swamp and captured Fort Davis before continuing the full sweep of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s lines all the way to Hatcher’s Run. “Four pieces of artillery were captured by members of the regiment, 400 prisoners and two flags,” reported Lt. Col. Binkley. “The flags were captured by Private Isaac James, Company H, and Sergt. Francis M. McMillen, Company C; the latter also captured one piece of artillery.”

For his role in the decisive battle of the lengthy campaign, McMillen enjoyed a promotion to sergeant major. His reward was followed up further on May 10, 1865, when he joined many fellow distinguished soldiers in the receipt of the Medal of Honor for his flag capture on April 2nd.

Francis McMillen returned to Ohio after the war as a farmer and was married twice with two children. He died in 1913 while at the Central Branch of the National Military Home in Dayton. I found his diary among the manuscript collection of the J.Y. Joyner Library at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina.

Interesting tale; thanks for posting !

Hmmm…that’s a little sad that he didn’t write more, but I agree that the pocket was probably the safest place for the journal. Great article!

It would be most interesting to know more about Sgt Major Francis McMillen’s early family history, and when/how they arrived in America. I am a descendant of James McMillen who was with Gen Washington at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778. His family arrived in Freehold, Provence of New Jersey, in 1749, having escaped Scotland after the Battle of Culoden, 1746. James had uncles and brothers who moved west, possibly into Kentucky/Ohio in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s.

Caroline Miller, Augusta, Ky., Bracken County, KY

McMillen was born and lived several years near Augusta. At the Historical Society, we believe we have some information on his early family. I’ll have to get out my folder.

I’ll e-mail you so you will have my address, etc.

Caroline R. Miller, P. O. Box 8, Augusta, KY 41002

We had one ceremony a few years ago in his honor – bronze plaque in the courthouse.

We really want to do more – just sooooo many projects!

Caroline