One of America’s First Christmas Trees

ECW is pleased to welcome guest contributor Richard G. Williams, Jr.

Earlier this month, I, along with a number of some of my children and grandchildren, embarked on an annual pilgrimage. We made our way down a narrow dirt road here in the Shenandoah Valley to a Christmas tree farm. There, we scattered to scout out a perfect specimen.

After a lengthy debate and judging contest I, along with the assistance of one of my granddaughters, chose a couple of perfect trees and loaded them on my truck.

Of course, this tradition is not exclusive to Virginia, though we Virginians are able to proudly claim to be home to one of the first Christmas trees in America. The man responsible for this claim was the Reverend Charles Frederick Ernest Minnigerode (1814-1894).

Minnigerode is more widely known as rector of the “Church of the Confederacy” — St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, where he ministered for 33 years and where both Gen. Robert E. Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis worshipped.

Born in Germany, young Minnigerode was thoroughly educated in the classics and confirmed to the Lutheran Church at the age of 15.

Entering the University of Giessen to study law in 1832, Minnigerode soon became embroiled in the raging political debates that engulfed Germany at that time. Things came to a head in 1834. Minnigerode, who wanted to help establish a democratic Germany, was accused of being a “revolutionary,” arrested and thrown into prison. For the next four years, he languished in various prisons, even spending some of that time in ancient German dungeons.

For most of the time Minnigerode was imprisoned, he was allowed only one book — the Bible. Tradition has it that he read it through eight times — memorizing much of what he read during his lonely hours of solitude.

This prison experience with “God’s book” would serve him well in his future role ministering to dejected Richmonders who, like Minnigerode, would also know lonely hours and experience their own form of imprisonment.

Eventually, Minnigerode became ill from exposure in the dank prisons and jail officials worried that he might die. Not wanting that responsibility, they put him under house arrest and released him to the care of his brother and father.

Finally freed from house arrest in 1839, Minnigerode concluded he would always be under suspicion in Germany. Some rumors persist that the young German was also involved in a duel and forced to flee his homeland.

Whatever the circumstances, Charles Minnigerode decided he could not remain in Germany. He sailed to America arriving in Philadelphia in December of 1839. The ten week ocean voyage evidently improved his health. One writer noted that he landed “well and free for the first time in more than four years.”

Learning to speak English fluently in just three months, Minnigerode soon found himself teaching Greek, Latin, and Hebrew as well as German. This would prove to be only temporary, however. Reading of a call in a newspaper for a position teaching ancient languages at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Minnigerode applied. Initially facing strong opposition as a “foreigner,” the young scholar had to compete against 30 other well-qualified applicants. George Blow, a member of William and Mary’s Board of Visitors, later wrote:

“Testimonials of about thirty candidates were examined. … The overwhelming certificates, letters of recommendation and evidences of qualification, of splendid attainments and other requisites for a professor, were so overpowering, that it left not a doubt or hesitancy in the minds of the visitors as to a choice, and on the first ballot Minnigerode was elected. … He is one of the best educated men in this country, and unsurpassed as a Classicist, writing Hebrew, Greek, & Latin with perfect ease & elegance.”

“Testimonials of about thirty candidates were examined. … The overwhelming certificates, letters of recommendation and evidences of qualification, of splendid attainments and other requisites for a professor, were so overpowering, that it left not a doubt or hesitancy in the minds of the visitors as to a choice, and on the first ballot Minnigerode was elected. … He is one of the best educated men in this country, and unsurpassed as a Classicist, writing Hebrew, Greek, & Latin with perfect ease & elegance.”

And so Minnigerode moved to Williamsburg, Virginia in 1842. There professor Minnigerode soon met Judge Nathaniel Beverly Tucker, who was a professor of law at William and Mary, and the two men soon became friends. That same Christmas, Tucker invited his new friend to share the holiday with his family at Williamsburg’s famous St. George Tucker House.

As a gift to Tucker’s children, Minnigerode shared the history of the German tradition of decorating a Christmas tree. He selected a small evergreen and had it cut and brought into the Tucker residence.

Minnigerode helped the young Tuckers assemble strings of popcorn and colorful paper decorations. According to one of the Tucker descendants, the tree was set on the parlor table, where “regular sized candles were cut down and fastened on the tree, nuts were gilded, and other ornaments made. Presents were probably not distributed at this time, but there were songs, games, and refreshments.”

Thus began a tradition that is repeated in millions of American homes every December.

Minnigerode changed his church affiliation in 1844 and became an Episcopalian. He would write later, “I would have connected myself with the church sooner had I not felt that I could not stop there; but once in the church, I would also enter the ministry.” In 1845, he announced his call to the ministry.

In 1846, Virginia’s bishop, the Rev. John Johns, presided over Minnigerode’s ordination as a deacon. One year later, Johns ordained the German into the Episcopal priesthood. Both services took place at Williamburg’s historic Bruton Parish Church. After serving a number of parishes, the Rev. Minnigerode was called to St. Paul’s in Richmond in 1856. He would serve there as pastor for 33 years — until 1889.

It was at St. Paul’s that Minnigerode’s impact on American history was most dramatic. Brilliant, charismatic and very fond of music; combining his knowledge of Scripture with his love for the souls of men and with his command of the English language, he left an unforgettable impression upon all who attended St. Paul’s.

Here he preached to the Prince of Wales, baptized many in the Confederate leadership, presided over J.E.B. Stuart’s funeral and eulogized President Monroe at his reinterment in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery.

During the Civil War, the German who had been thrown in jail for his “revolutionary” ideas became known as “Father Confessor of the Secession,” “Father Confessor of the Confederacy” and the “Rebel Pastor.” The constant stream of Confederate officers, soldiers and government officials into St. Paul’s earned it the sobriquet “Cathedral of the Confederacy.”

Minnigerode’s relationship with President Davis was especially intimate; the two men often discussed spiritual matters. Minnigerode wrote of Davis: “He spoke very earnestly and most humbly of needing the power of the Holy Spirit; but in the consciousness of his insufficiency felt some doubt … but soon it settled this question with a man so resolute in doing what he thought was his duty.”

Duty also was important to the preacher’s family; he had two sons who fought for the Confederacy.

However, duty was not enough for the South. On Sunday, April 2, 1865, a courier delivered a message to Davis as he sat in his pew at St. Paul’s. It was Holy Communion Sunday. The communique was from Gen. Lee. Petersburg had fallen and Richmond would be next. The Confederate government must evacuate as soon as possible.

Davis fled south but was soon captured and held in solitary confinement at Fort Monroe, Virginia. But Davis would not be forgotten by his pastor. Minnigerode was the first civilian allowed to visit the shackled Davis, and his own prison experience enabled him to identify with his former president. So touching were their conversations, prayers and communions during these visits that Davis’ jailer was said to have stood at the mantel in an adjoining room, his face in his hands.

Minnigerode would say later that “those were the most solemn communions of which I ever partook.” Upon being released, Davis would tell his Christian friend: “You have been with me in my sufferings, and comforted and strengthened me with your prayers, is it not right that we now once more should kneel down together and return thanks?”

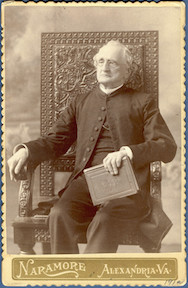

Minnigerode resigned from St. Paul’s in 1889 because of the infirmities of age, but he would serve for the next five years as chaplain for Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria. He died on Oct. 13, 1894, and was laid to rest in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. His headstone bears a fitting epitaph: “He has fought a good fight. He has finished his course. He has kept the faith.” And, we could add, he decorated one of America’s first Christmas trees.

* * *

Richard G. Williams Jr., is a writer and the author of four books related to the Civil War. His latest, The Battle of Waynesboro, (The History Press, 2014), was part of The History Press’s Sesquicentennial Series. He’s also had three essays published for The Essential Civil War Curriculum which is an online Sesquicentennial project at the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech. Williams serves on the Board of Trustees for the National Civil War Chaplains Museum in Lynchburg, VA and blogs at oldvirginiablog.blogspot.com. He writes from the Shenandoah Valley.

* * *

(Adapted from an article that originally appeared in The Washington Times, Friday, December 8, 2006. Used by permission.)

Sources:

Woodworth, S. E. “Charles Minnigerode (1814–1894).” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 9 July 2009. (See: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/minnigerode_charles_1814-1894)

Gill, Harold B. Jr. “Christmas Trees, the Confederacy, and Colonial Williamsburg.” The Colonial Williamsburg Journal (See: http://www.history.org/almanack/life/christmas/hist_reverend.cfm)

Minnigerode, Rev. Charles. Sermons by the Rev. Charles Minnigerode, D.D., Rector of St. Paul’s Church, Richmond, VA. Richmond, VA: Woodhouse & Parham. 1880. The Internet Archive.

Palmer, Vera. “Immigrant Boy to St. Paul’s Rector.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 11 November 1934.

Minnigerode is very interesting: Less so for his introducing the Christmas tree into a non-German setting, than for his reconciliation with the very different religious and political opinions in his new world: A German Lutheran, an early “democratic” revolutionary in his own land, comes to America, adapts himself to regional politics and religious expression, enters the church of the societal leaders, and serves as confessor to a different sort of revolutionary.

Thank you, Mr. Williams, for the article and the sources. This fellow will repay some study.

David – I agree and you’re welcome. I expressed the same sentiments to Chris. Minnigerode had quite the career in very tumultuous times and makes a great study. He deserves a modern biography.

“Old Dominion,” makes his appearance in these pages ! Congratulations and interesting article !

Thanks David! Yes, you just never know what the cat might drag in. 😉 Professor Mackowski was very gracious to post the piece.

Thank you, ECW, for this well-written, informative post. Some of those Yankee relatives of mine were just a little too uptight for much actual celebration, no matter what the occasion. Huzzah for Christmas trees!