When General Lee Cried

One of the excitements of writing history comes when one finds a story that’s fresh, new, or hasn’t yet made its way into the accepted secondary literature.

One of the excitements of writing history comes when one finds a story that’s fresh, new, or hasn’t yet made its way into the accepted secondary literature.

I have one I’d like to share.

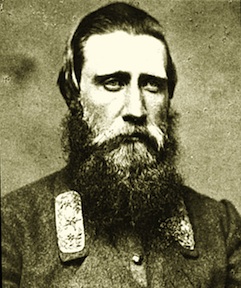

For Savas Beatie, I’m finishing a book-manuscript with the working-title Spurs Without Greatness: A Study of John B. Hood’s Generalship in 1864. Of course you have to start at the beginning, so I’ve written a prologue that summarizes Hood’s early military career and Confederate service through 1863 to his few months spent in Richmond while he convalesced from his Chickamauga wound.

Flashback to August 1862, Second Manassas.

On the second day, having helped clear the field of Yankees with the charge of his Texas Brigade, Hood saw a few Federal ambulances in his front, and sent forward some of his Texans to bring them in. He distributed the wagons among his units. When Brig. Gen. Nathan (“Shanks”) Evans, Hood’s nominal superior that day, heard about this, he ordered Hood to turn over the captured ambulances to his own brigade.

Hood refused. “Whereas I would cheerfully have obeyed directions to deliver them to General Lee’s Quartermaster for the use of the army,” he later wrote, “I did not consider it just that I should be required to yield them to another brigade of the division, which was in no manner entitled to them.” Evans reported this to General Longstreet, who placed Hood under arrest and sent him to Culpeper Courthouse to await court-martial.

General Lee intervened, overruled Longstreet, and sent Hood back to his command, albeit without authority to issue orders.

When the army prepared to cross the Potomac into Maryland, Hood was still under arrest, but rode with his troops. He now commanded a small division: his brigade of Texans, plus that of Brigadier Evander Law.

The Texas Brigade was marching past General Lee when the Texans began to shout, “Give us Hood! General Lee, give us Hood!”

Lee was visibly moved. “You shall have him, gentlemen,” he answered.

The next day at White’s Ford, Hood’s troops reached the river, and General Evans ordered them to wade across. But the men refused to obey any command save their own general’s. Hood appeared and directed them to ford the river, and they did.

After McClellan got hold of Orders 191 and the Federals began moving on South Mountain, Lee and Longstreet needed every man to help hold the vital passes. Hood’s troops were called in, but the Texans balked.

On the afternoon of September 14 near Boonsboro, as they marched toward the sound of battle, again they yelled, “Give us Hood!”

General Lee was in a fix. He called for Hood, who rode up and dismounted.

“General,” as Hood remembered Lee saying, “here I am just upon the eve of entering into battle, and with one of my best officers under arrest. If you will merely say that you regret this occurrence, I will release you and restore you to the command of your division.”

Hood respectfully explained why he could not do so.

Lee asked once more, and again Hood declined.

The commanding general had no choice but to give in: “Well, I will suspend your arrest till the impending battle is decided.”

When they heard this good news, Hood’s sodliers cried out, “Uncle Robert has released General Hood!” and “Hurrah for General Lee! Hurrah for General Hood! Go to hell, Evans!”

Hood proudly rode to the head of his division and resumed command of it.

This much of the story is familiar, appearing in Hood’s memoir, Advance and Retreat, and the standard histories.

The next part, though, gets rich.

Maj. R. W. York of the 6th North Carolina (in Law’s brigade, Hood’s division) seems to have been close by when Hood and Lee conversed at Boonsboro. As Lee spoke–“Here I am going into an important battle”–Major York saw “the big tears were rolling down Gen. Lee’s cheeks, plowing their little furrows through the dust upon his noble face.”

After the war, in 1873, York ran into General Hood and the two veterans sat down to talk about the war. York brought up the time when Hood had refused to apologize to General Lee, and asked if he also remembered it.

“‘Yes,’ said he, ‘I do, and shall as long as I remember anything.'”

York recorded further his conversation with Hood: “He alluded feelingly to his great Commander being unable to restrain his tears, and as Gen Hood related the incident to me, the big tears came unbidden to his own eyes.”

Wow! Where’s that in the literature?!

I happened to find the story in an article York wrote in1875 for Our Living and Our Dead, the literary-historical magazine published in North Carolina for a few years during the mid-1870s.

The Emory University library has the periodical, so imagine my delight in finding York’s reminiscence, “General Hood’s Release from Arrest–An Incident of the Battle of Boonsboro,” Our Living and Our Dead, no. 2, (June 1875), 420-23.

It’s just another instance of gaudium eruditionis–the joy of knowledge!

Steve: This sounds like a worthwhile project. And it’s interesting to learn that Stonewall wasn’t the only commander in the ANV with a saddlebag full of arrest warrants.

Thanks, John, Just when we think we’ve learned everything there is about General Lee, someone stumbles on another new story. Chris Mackowski’s blog for the ECWS is just the place I had been seeking to get this one out!

We are looking forward to this study, Mr. Davis.

Ted–this is the kind of story I have found that lets me think that in our forthcoming work, we might even be contributing to the literature!