The Cosmopolitanism of the Union Army: What Did It Mean?

I was recently assessing the demographic makeup of Union and Confederate armies in my Civil War and Reconstruction class when one of my students asked a thought-provoking question: “What percentage of the Union Army was northern, white, English-speaking, and native-born?”

My impromptu response was to say about half, given that the Union ranks included at least 100,000 soldiers from the Confederate states, 200,000 soldiers from the Border South, 200,000 African Americans, and more than 500,000 foreign-born soldiers, most from Germany and Ireland. I didn’t broach the semantic debate over “Northern,” which was as often a political as a geographic term. (Some of my Lower Middle Western Unionists rejected it outright.)

But I was subsequently surprised by the seeming paucity of scholarship and hard data on this topic, and I am still on the lookout for a single source that weighs competing estimates of nationalities and ethnicities within the Union ranks. (Scholarly discussions of the problem of determining African American numbers in the Union Army go back to at least Dudley Taylor Cornish’s The Sable Arm in 1956.)

Although countless works have underscored race, ethnicity, and nationality in particular contexts, of course, and David Gleeson and Anne Bailey have even scrutinized ethnic minorities in the Confederacy, less has been written on broader role of cosmopolitanism in the Union Army despite the recent trend of placing the Civil war within the context of other nineteenth century revolutions in Europe and South America.

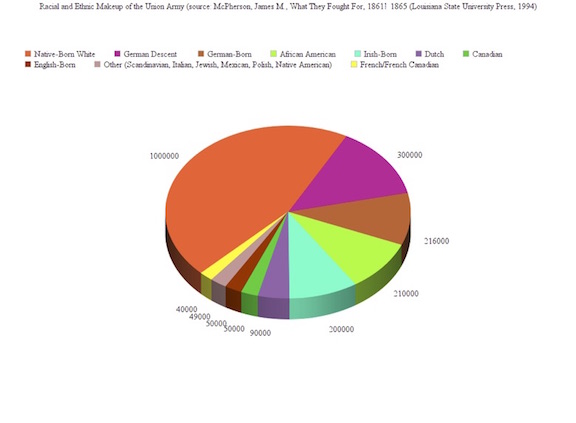

James M. McPherson’s For Cause and Comrades (1996) provides some of the most precise statistics on the Union Army’s racial and ethnic makeup. (This data can be found online here.) Using McPherson’s numbers, one gets a sense of the scale of ethnic, racial, and cultural diversity within the Union Army:

However, as native-born whites and African Americans were born in both northern and southern states, these figures do not account for the other component of my student’s question: region of origin. Luckily, Bill Freehling, in his estimation of “Southern anti-Confederates,” and others provide some estimates as to what percentage of African American soldiers hailed from slaveholding states and how many white Union soldiers enlisted from the Border South and the Confederate states. (Freehling’s rough estimate is that at least 450,000 black and white southerners fought in the Union Army.)

Though imperfect, these data sets suggest several things:

- A slight minority of the Union soldiers were probably born in the North

- Roughly 300,000 of those approximately 1 million northern-born Union soldiers were of German descent

- As such, English-speaking (first language) northern-born white men in fact comprised a decided minority (though a clear plurality) of the Union Army, and their numbers were likely somewhere in the neighborhood of 750,000 out of the 2.2 million men who served

- I might conclude to my student that English-speaking northern-born white men constituted about one-third of the Union Army.

Now for the next set of questions. These numbers seem exceptional, but just how diverse was the Union Army in relative terms? What did its variety mean, particularly given the rates at which different ethnic groups “Americanized”?

I know of no such source that compares the heterogeneity of the Union Army with that of other multinational and multiethnic nineteenth century volunteer or coerced service armies. How, for instance, did the Army of the Potomac equate in its cosmopolitanism with Napoleon’s Grand Armée, the monarchical forces of the Hapsburg or the Tsars, Garibaldi’s revolutionary nationalists, or the British Madras?

Additionally, synthesizing soldier studies and more recent efforts to internationalize the Civil War (think Andre Fleche’s The Revolution of 1861 or Don Doyle’s The Cause of All Nations), future scholars might weigh in on the ideological implications within the ranks of this interracial, interethnic, and international Unionist coalition. Though previous studies have touched on how ethnic and linguistic diversity impacted the culture and organization of various Union armies, corps, and regiments, a broader appraisal might be useful in addressing the distinctiveness of the Union Army experience from ethnic, racial, and national perspectives, and in speaking to the social and political practice of war. Adding to Fleche’s “transatlantic dialogue,” scholars might use ethnic, linguistic, religious, and racial diversity and interaction in the ranks to examine in what ways pluralism influenced how soldiers communicated, constructed notions of manhood and nationalism, and thought about everything from the political economy and republicanism to conceptions of death and physical space.

This commentary is not a formal call to arms but a post-class exercise and hope for further discussion and some collegial guidance. (If nothing else, I’d like to provide my student a more satisfactory answer next time.)

In the first pie graph, what is the difference between native-born white and german descent?

My great grandfather served. He was first generation Irish. How was he carried in your graph? What generalizations are professional historians willing to make based on the ethnic background of the Union soldier? Whatever your answers, I really like the discussion you generate with your work.

Thanks for your article. BTW, 60% of Union Navy personnel were immigrants or blacks. http://www.longislandwins.com/columns/detail/the_immigrant_in_the_union_navy

According to the first pie graph 90,000 Dutch (born??) soldiers served in the Union Army. According to my own research there were less than 1,000 of them. The number of 90,000 is much too high, even when the soldiers from Dutch descent are included. There was only one unit, the I Company of the 25th Regiment Infantry of Michigan, that was almost completely Dutch. The boys of this company used to sing psalms in Dutch at their campfires and they did an outstanding job at the Battle of Tebbs Bend, Kentucky on July 4th 1863 against John H. Morgan. Those who survived the war were ofcourse completely Americanized when they returned home.