Sailors Are Not Soldiers

Dwight Hughes

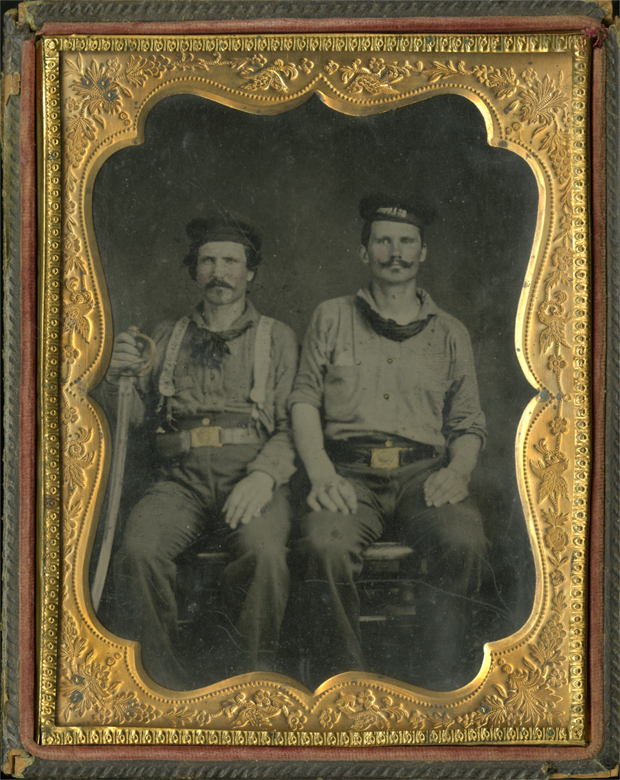

Civil War deep-water sailors—North and South—were not like soldiers. They came from very different backgrounds and fought a much different war. “[They] looked, moved, and talked like typical sailors,” noted one study.

“Ruddy cheeks worn by the sun and wind, scars from working with wood and metal, and clothes tarred for waterproofing all found their impressions on their bodies and faces. Moreover, the collective nature of shipboard details lent an unmistakable rhythm to their movement. They communicated using precise, technical terms, peppered with colorful, often obscenity-riddled analogies. Sailors made their points quickly, often drawing metal pictures with their words. Phrases like ‘learning the ropes’ and ‘versatile as a monkey’ achieved a certainty of expression, unmatched on land.”[1]

This description is remarkably similar to one written in the seventeenth century, which says of “a sayler” that, “he is an Otter, and Amphibium that lives both on Land and Water…. His familiarity with death and danger, hath armed him with a kind of dissolute security against any encounter. The sea cannot roar more abroad, than he within, fire him but with liquor…. In a Tempest you shall hear him pray, but so amethodically, as it argues that he is seldom versed in that practice…. He makes small or no choice of his pallet; he can sleep as well on a sack of pumice as a pillow of down. He was never acquainted much with civilities; the Sea has taught him other Rhetoric. He is most constant in his shirt, and other his seldom washed linen. He has been so long acquainted with the surges of the Sea, as too long a calm distempers him. He cannot speak low, the Sea talks so loud…. He can spin up a rope like a Spider, and down again like a lightning. The rope is his road, the topmast his Beacon…. Death he has seen in so many shapes, as it cannot amaze him.”[2]

There had been no professional naval enlisted service; sailors enlisted for the extent of the warship commission, during which they belonged to the ship not to the navy. Recruiting was difficult and seldom attracted the best candidates to what could be a singularly harsh and forbidding environment. Seamen encountered aristocratic officers for whom leadership was primarily iron discipline, along with narrow-minded petty officers enforcing that discipline with short, thick rope “colts” or “starters,” and devious, hard-bitten veteran “topmen” or “sheet anchormen” who formed a society that excluded and ridiculed the newcomer. Morale was often poor and not usually an issue with which officers concerned themselves. “A rough equilibrium between sullen defiance and conformity seems to have been the norm in naval ships,” wrote another historian.[3]

In further contrast to soldiers, most mariners on both sides were products of poor and working classes from Northern and European cities rather than small towns and farms. At a time when America was still eighty percent rural, these men represented the burgeoning urban, industrial environment. Many were foreigners fleeing hunger and economic turmoil in blighted slums and factories where living could be harsher than at sea. American crews—naval and merchant—had a long tradition of national and ethnic diversity. Antebellum congressmen, officials, and officers became so concerned with large numbers of foreign-born sailors that they tried unsuccessfully to limit their presence.

Admiral David Dixon Porter once referred to, “As fine a body of Germans, Huns, Norsemen, Gauls, Chinese, and other outside barbarians as one could wish to see, softened down by time and civilization….” In the Union navy, sailors born abroad constituted 45 percent of total enlistees as evidenced by recruiting samples, with the Irish alone providing 20 percent despite, or perhaps because of, their stereotypical reputation for mental thickness, chronic laziness, and drunkenness.[4]

From the founding of the nation, freedmen and escaped slaves also had served afloat in both warships and privateers, hazarding their lives against the nation’s enemies while finding respect, relatively fair treatment, and economic opportunities not available ashore. Nor were they restricted to menial jobs, but also held petty officer positions equivalent to white crewmen.

From the founding of the nation, freedmen and escaped slaves also had served afloat in both warships and privateers, hazarding their lives against the nation’s enemies while finding respect, relatively fair treatment, and economic opportunities not available ashore. Nor were they restricted to menial jobs, but also held petty officer positions equivalent to white crewmen.

Through the Quasi War with France, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War, economic growth and westward expansion generated continuing shortages of sailors. Restrictions on the enlistment of foreigners and a general bias by white mariners against naval service created additional opportunity for blacks, although they did generate controversy, adding fuel to antislavery arguments in debates on the meaning of liberty. Such service did not materially improve black lives ashore, however, and peacetime efforts were made to exclude them from the navy, but precedents were established in a service historically more integrated than the army and with generally equal compensation and treatment.[5]

Blacks continued to enlist in substantial numbers through the 1820s and 1830s. Southern officers increasingly brought slaves on board or enlisted them and collected the salaries. As the issues heated up, Northern political backlash led to severe restrictions on employment of slaves afloat. At the same time, economic hardship was forcing many whites back to sea taking available berths. By 1861, African Americans constituted only about 2.5 percent of crewmen, but as the war exploded so did both navies. Quietly, out of public view, and with much less controversy, the Union sea service led the way in employing contrabands, enlisting them in significant numbers long before the army did despite inherent legal ambiguities.[6]

A navy desperate for seamen could not quibble about origin. It was still very much a hierarchical class system, evolved over centuries to the unique requirements of shipboard life and hardly less strict than slavery, but race played little direct role. This was just as true of the Confederate Navy, at least on its far-flung cruisers. (The situation aboard Rebel coastal and river forces reflected a mix of army and navy influences with soldiers or converted soldiers often helping to man vessels under navy officers.)

The CSS Shenandoah was typical for Rebel ocean commerce raiders. Commissioned officers were Americans, predominantly of English and Irish descent. Non-commissioned warrant and petty officers were primarily English and Irish, while the crew was mostly English, Irish, Scandinavian, and German but also, South Asian, and Pacific Islander, with a few Yankees, and several African Americans. Most were merchant sailors recruited from captured vessels and foreign ports with promises of high pay and prize money, who had never set foot on American Soil.

All were enlisted according to their skills and experience regardless of ethnicity. Even considering the prejudices of their time, Union and Confederate officers were experienced in a cosmopolitan service long accustomed to foreigners of all shades. It would have been disruptive of efficiency and discipline to place one group of men into a separate category based on race and treat them differently. There was neither need nor room to make such distinctions in the close confines of a ship at sea.

Sailors also tended to possess a different set of values and ideas: they were inclined to be hard, pragmatic, cynical, and profane men who drank too much, fought too much, and prayed too little. Aggressively masculine, they did not generally aspire to gentlemanly virtues, sacrificial aspirations, or ideological motivations. Huge numbers of immigrants, former slaves, and working-class men enlisted for individual rather than collective reasons—practical factors of economic need, ethnic tendencies, class outlook and race. Aside from the few and infrequent actual battles, their war was marked by personal struggles with boredom, officers, religion, and alcohol.[7]

But despite his cynicism, a seasoned mariner understood that intense training, immediate compliance, close teamwork, and often extreme and dangerous exertions were required for survival through perils of sea, storm, and battle. Coming from a rough background and experiencing the harshness of life at sea, he bonded with crewmates, took intense pride in maritime skills and courage, developed emotional attachment to the vessel—and by extension to the cause she represented—and would engage in almost superhuman effort on her behalf. If required, he could fight like a demon. When on shore, insults to his ship or shipmates by outsiders were likely to bring forth sudden and violent retribution.

The boundaries of life at sea were well defined, the limits of their little world easily understood, the horizon unchanging for weeks or months on end. They knew their places in the precise hierarchy of discipline and responsibility, cogs in the giant machine of the ship. They took each day as it came, did what they had to and resisted what they considered unnecessary, carrying out the unending routine of shipboard life while looking no further ahead than the next port and the drink and women to be had there. They were normally wet, often cold, frequently exhausted, and often subsisted on meager fare of salt meat, hard, moldy bread, stale water, and grog. Without this kind of man, a warship was just a lifeless, purposeless object.

[1] Michael J. Bennett, Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 99-100.

[2] Samuel Eliot Morrison, The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages, A.D. 500-1600 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), 132. (Edited for clarity and spelling.)

[3] James E. Valle, Rocks & Shoals: Naval Discipline in the Age of Fighting Sail (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1980), 15, 16.

[4] Valle, Rocks & Shoals, 19; Bennett, Union Jacks, 9.

[5] Steven J. Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens: African Americans in the Union Navy (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002), Chapter 1, “America Has Such Tars,” 6-24; Dennis J. Ringle, Life in Mr. Lincoln’s Navy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 11-13.

[6] Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens, Chapter 2, “The Wants of the Service,” 25-53; Ringle, Life in Mr. Lincoln’s Navy, 13-15.

[7] Bennett, Union Jacks, x-xi.

An Interesting look at naval life most of us land lovers never realized . Thank you for a eye opening account of life on the sea .

Bennett’s book is highly recommended.

Enjoyed the article very much! Do you think the decline of the American whaling industry (compared to its height in the 1840’s) may have contributed to the ethnic diversity in the Civil War era navies? Sailors – former whalers – were willing to take a navy job to have work?

Glad you liked it, Sarah. It is reasonable to presume that the decline of the industry led some into the navy, but I have seen no specifics. I do know that a severe shortage of recruits developed in New England by mid-century, and many sailors in the Pacific whaling fleets were recruited from the Pacific Islands, particularly Hawaii. Of the four whalers captured by Shenandoah in Pohnpei, almost all crewmen were islanders, as were many in the prizes taken in the Arctic.