The Rebirth of the Army of the Potomac (part three)

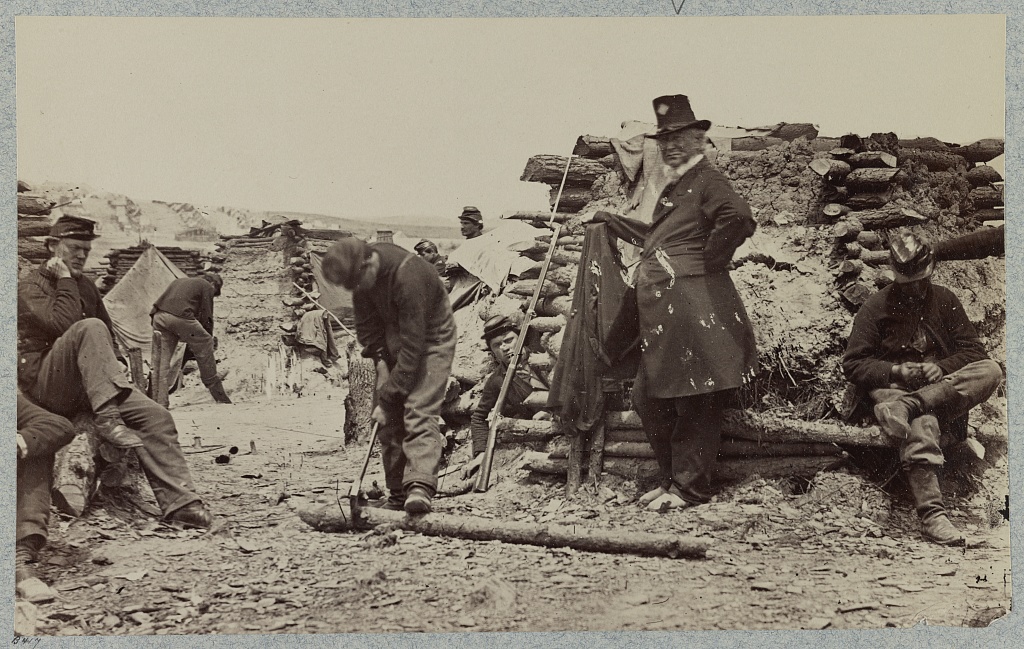

Camp Health and Winter Huts

Camp health and cleanliness was also a major concern. Most of the enlisted men spent their winters in small huts, reminiscent of those used by Washington’s Army at Valley Forge. The major difference between the huts of the Revolution and Civil War was that many Union and Confederate soldiers dug a large hole in the ground. They then stacked logs, like a small log cabin, then normally topped the hut with two or more shelter tent halves as a roof.[1] Many of the huts included small fireplaces for cooking.[2] Due to a lack of bricks, and the abundance of solders, many fashioned their chimneys out of wood, which combined with the canvas rooftops, often led to fires “house fires”. These small domiciles normally housed 4-10 men.

Charles Haydon of the 2nd Michigan described his modest hut:

At three PM Moore & I, aided by the cook and Benjamin the contraband, with many misgivings, commenced [building] a fire place. Three hours after the chimney had risen to the height of four and a half feet….It draws strongly, blazes cheerfully, & fills the whole tent a genial warmth. Our house is 8 feet square, built 3 feet high, with pine poles on the top of which is perched an ‘A’ tent. A bed made of poles, a box, a board which answers both for a table and bench constitute the furnishings. At home what a state of wretched poverty this would indicate…Give me a fire place which will not smoke & this rat hole will give me more pleasure than a king desires from his palace. The fire place looks like the one at home at least in that there is a fire in it.[3]

The winter of 1862 saw the addition of many green units to the Army of the Potomac. One of these new regiments was the 140th Pennsylvania. The “fresh fish” joined the army in the days following the disaster at Fredericksburg, and were assigned to Brig. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s 2nd Corps division. With in days of their arrival the Keystone State men were at work constructing huts. The men “felled trees mostly of pine, right and left, shaped them into logs of suitable length, and with these constructed the framework of our winter huts.”

The units historian went on to vividly describe their living quarters:

“The enclosure of logs which was usually about four or five feet high was plastered inside with Virginia mud or clay. An opening large enough for a fireplace was cut on the backside, and outside this opening a semicircular back wall was made by driving stout stakes closely together. Inside this, about eight inches or more, a corresponding wall of lighter stakes was constructed after the same fashion…..The portion of the chimney above this was rudely constructed fireplace was made of split sticks, built up like the corncob houses of our childhood days, and thickly plastered with mud….The inner row of stakes which gave direction to the curve of the fire place burned out gradually, as they became dry, but by that time the mass of mud which they supported, had become sufficiently hardened to make a safe and substantial back wall. A drop curtain of a section of a shelter tent screened the entrance to the hut and to a limited extent protected its inmates from the cold blasts which swept through the company streets.

The roof was made of joined sections of shelter tents. A ridge pole supported on notched boards nailed as uprights to the logs, gave the desired pitch and the muslin cover, which was stretched over it, was nailed fast to the upper tier of logs on either side….Six occupants, designated as bunkmates, were allotted, at the outset of each hut. At night they were stowed away on an upper and lower berth made of a log frame and slatted with long flexible poles placed closely together lengthwise. The mattress, which was regarded as an essential feature of this spring bed, for reasons that are evident, was usually made of muslin or gunnysack filled with hay, dried grass, leaves or straw. The lower berth was made a foot or more wider than the upper one and in the daytime was used as a divan or sofa. There was enough space between the berths and the fire place to admit of seats, including the projection of the lower berth for all the occupants. This space was designated as the kitchen, and the cook for the week had the post of honor in the chimney corner.”

Men of the 127th Pennsylvania looked to improve their camp. If there were no brick kilns close by they would improvise. The soldiers”discovered a southern Methodist church…which they appropriated because their congregation were secessionists, and the late pastor deserted it for a chaplaincy in the Confederate Army.” The Pennsylvanian’s “tore it [the church] down brick by brick, carrying those bricks to camp and utilizing them for chimneys, which they built in or at the end of their tents; and in laying small pavements in front of their quarters to protect them from the Virginia mud of memorable sticking quality.”

The soldiers living in these small domiciles did their best to make them feel more homey. Mantles were added to the fire place. Some men constructed benches, chairs, tables, any substitute for the comforts of home. Jacob Bechtel lamented that the men were “All stowed away in one coop compases [sic} a happy groop [sic], we feel at Home once more in our log hut.”

Officers normally fared better than the men when it came to accommodations. High ranking officers took over the large homes of the area including Little Whim-Marsena Patrick’s HQ, Boscobel-Dan Sickles HQ, and Bell Air-David Birney’s HQ.

Line officers typically had small cabins of their own. The men of Company D, 2nd Rhode Island Infantry built a “house” for their acting company commander 2nd Lt. Elisha Hunt Rhodes. Rhodes proudly described his modest home.

“On the first floor we have a fireplace and table. Upstairs on a shelf we have a bed and a ladder to reach it. The floor of the second story only covers part of the room and in fact is the bed. The walls are of hewn timer with spaces filled with mud. The roof is pieces of a shelter tent. We moved in this evening and feel very happy in our new home.”

The diet of the men and the cleanliness of these huts were of major concern to Dr. Jonathan Letterman. The thirty-eight year old Canonsburg, Pennsylvania native served as the Medical Director for the Army of the Potomac, and was a carryover from both the McClellan and Burnside administrations. Letterman was a well educated at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After his 1849 graduation Letterman joined the Army Medical Department. He was a much respected doctor, with a face that was “worn in the cause of suffering…” In time he would earn the moniker “Father of Modern Battlefield Medicine.” Hooker gave Letterman free reign to implement his policies and ideas.

Some officers and men lacked common sense, which goes a long way to keeping an army healthy. Letterman helped to lay out camps properly, moving some regiments and brigades to better camp grounds. He had wells placed away from the “sinks” (latrines). The men of the 13th New Hampshire were using Claiborne Run, in Stafford County, as their source for all water needs. “The men and officers performed their morning toilets here. Muddy boots, smutty kettles, and soiled clothing were scrubbed here; and some huge fools used the water for cooking…” recalled the regimental historian.[4]

“Our present camping ground is an excellent selection, being upon an almost level field, near one hundred feet above the level of the river, and bounded on all sides by deep ravines,” penned a member of Captain Alonzo Snow’s Battery B, Maryland Light Artillery.

Letterman ordered the canvas roof tops removed from the huts, which housed the men, twice a week (weather permitting). The good doctor viewed these huts as “abominable accommodations.”[5] The doctor also had a strong hand in the improvement of the soldier’s diet, having the men cook by companies, instead of individually. In this manner they were able to regulate rations and cleanliness. “Our rations come regular now.” Proclaimed one Minnesota soldier. “We get pork from Indiana, Pilot bread from New York, and fresh beef once in a while. Rice and coffee are in abundance, with plenty of sugar and salt.” Scurvy was on the decline in both hospitals and camps.[6] Any regiment that “were not scrupulously clean and orderly about their camp as they ought to be,” ran the risk of having any furloughs home revoked.

By late April the greatest risk to disease, were the more recent additions to the army. “I have never before seen the army in such good physical condition.” penned Thomas Galwey of the 8th Ohio. “The men are all fat, healthy, well uniformed, thoroughly equipped; the horses are prancing, the guns shining; and everything indicates an army in splendid fighting order.”[7]

In the end the changes made in the physical health of the men, lead to perhaps the healthiest period in the army’s history.

Endnotes:

[1] Jonathan Letterman, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac (New York, 1866), 103-107.

[2] Winthrop D. Sheldon, The “Twenty-Seventh.” A Regimental History (New Haven, CT, 1866), 35-37. The 27th Connecticut Infantry was a nine month regiment, who built 130 huts to house their regiment alone. In their case, the men rarely dug holes in the ground, but rather smoothed the ground and removed tree stumps, rocks, etc… from the living area. Once the exterior was completed soldiers often installed bunks, benches, mantles pieces over the fire place. They looked to recreate as much creature comforts from home as possible. Parts of Stafford County are still dotted with “hut holes”. Visitors can go to Pratt Park, adjacent to Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park’s headquarters at Chatham. Along their Frisbee golf course you can still see the depressions in the ground, left behind by members of the Iron Brigade. Recreations of the huts can be seen at the White Oak Museum, which is filled with artifacts from the Union Army’s winter encampment.

[3] Charles Haydon, Dec 24, 1862.

[4] Robert Laird Stewart, History of the One Hundred and Fortieth Pennsylvania Volunteers (Steubenville, OH: Regimental Association, 1912) 28-30. Regimental Association Committee, History of the 127th regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers: Familiarly Known as the Dauphin County Regiment (Lebanon, PA.: 1902),160-161.; Jacob Bechtel to Miss Becca, dtd. Dec. 24, 1862, in the Curatorial Collection of the Gettysburg National Military Park.; Diary entry of February 1, 1863, Elisha Hunt Rhodes, All For The Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes, ed. Robert Hunt Rhodes (New York: Orion Books, 1985), 98.; Gerard A. Patterson, Debris of Battle: The Wounded of Gettysburg (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997), 8.; Homer D. Musselman, Stafford County in the Civil War (Lynchburg, VA.: H.E. Howard, 1995), 47.

[5] Acquia to the Whig, dtd April 20, 1863, in Jerre Garrett, Muffled Drums and Mustard Spoons: Cecil County Maryland 1860-1865 (Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 1996), 181.; Letterman, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac, 103-104.

[6] M.H. Bassett, From Bull Run to Bristow Station (St. Paul, MN.: North Central Publishing Company, 1962), 24-25.; Letterman, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac,, 110. According to Letterman, new nine month and three year regiments that had very recently joined the army were not prepared for the hardships that war had brought. The camps of these recent additions were the breeding grounds for the vast majority of disease within the camps. Also see Letterman’s letter dated April 4, 1863 to Joseph Hooker discussing the improvements in camp health across the board. The letter also contains some of the concerns that Dr. Letterman had.

[7] Lieutenant L. N. Chapin, A Brief History of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment N. Y. S. V. Embracing A Complete Roster of All Officers and Men and A Full Account of the Monument Dedications on the Battlefield of Antietam September 17, 1902 (No Publisher or date of publication entered), 85. This book was published no earlier than 1903.; Thomas Francis Galwey, The Valiant Hours by Thomas Francis Galwey Eighth Ohio Infantry: Narrative of “Captain Brevet,” an Irish-American in The Army of the Potomac, ed. W. S. Nye (Harrisburg, PA.: Stackpole Books, 1961), 81.

I find it interesting, albeit perhaps of little importance, that the generals with whom Letterman worked best were Hooker & McClellan. Both were respected for, as you have entitled this series, giving the AofP a rebirth. I continue to wonder just what made these generals so ineffective as combat commanders. Saying they did not wish to tear down what they had worked to build up seems like a very simplified answer. Both McParlin and Barnes (successors of Letterman & Hammond) carried out the work begun, but under far less scrutiny and criticism.

Hooker was not an ineffective combat leader at the division and corps level. The main thing that hampered him when push came to shove, was, ironically, a breakdown in staff work. He left Butterfield at Falmouth where he was of little use to anyone. Once Hooker is wounded there is no one with the testicular fortitude to take the army from Hooker. Couch was not the man to do it. Butterfield was one of the few men in the army that knew what Hooker was up to as well.

He also allowed the guns at Farirview to fall silent because his chief of artillery was not given the freedom to operate, and thus was hanging out at Banks’ Ford over seeing artillery at an area that was not under threat yet. Hunt wasn’t there to funnel the necessary ammunition forward. Look at his actions on the 2nd and 3rd at Gettysburg and you see a very competent, and very active staff officer.

Hooker, unlike Little Mac, lead from the front. For all that can be said about the man, he was brave to a fault. He and his staff tried to personally rally the XI Corps men on the evening of May 2. He also tried to immediately right his wrongs by ordering troops into the gap he created in his lines. He was wounded. while overseeing the battle. Little Mac was nowhere near Malvern Hill when the battle was fought and never crossed the Antietam to assist his commander in the September battle.

When it comes down to it, Lee was in command of the ANV for nearly 1 full year prior to Chancellorsville. He commanded an army at the Seven Days, Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. He was a veteran commander by May of 1863, Hooker was a rookie, entering his first true campaign. Hooker wasn’t unwilling to place his men in harms way, he just screwed up when push came to shove. Over confidence was the bane of both McClellan and Hooker and it came back to bite them in the ass.