A Sharpshooter’s Postscript to Gettysburg, Part 6: “The Wagoners’ Fight” – A Battle To Hold Williamsport

Part six in a series.

We welcome back guest author Robert M. Wilson.

The long wagon train of the wounded led by John Imboden, a Brigadier General in the Confederate cavalry, filed into Williamsport during the afternoon and evening of July 5. The first of the hundreds of wagons on the forced march had begun their 40 mile journey late afternoon the previous day. As the caravan persevered through downpours and over rough, muddy roads, it had been intermittently attacked by Union cavalry and stormed once by angry axe-wielding Pennsylvanians. That ordeal had ended. But a whole new ordeal was about to begin.

The next day the wagon train was supposed to be in Virginia and heading towards Richmond. Instead, it sat clogging the river town’s streets. The rain swollen Potomac River was too swift and too deep to ford for the time being, and a band of Yankee marauders had destroyed the nearby pontoon bridge Confederate engineers had built for Lee’s invasion.

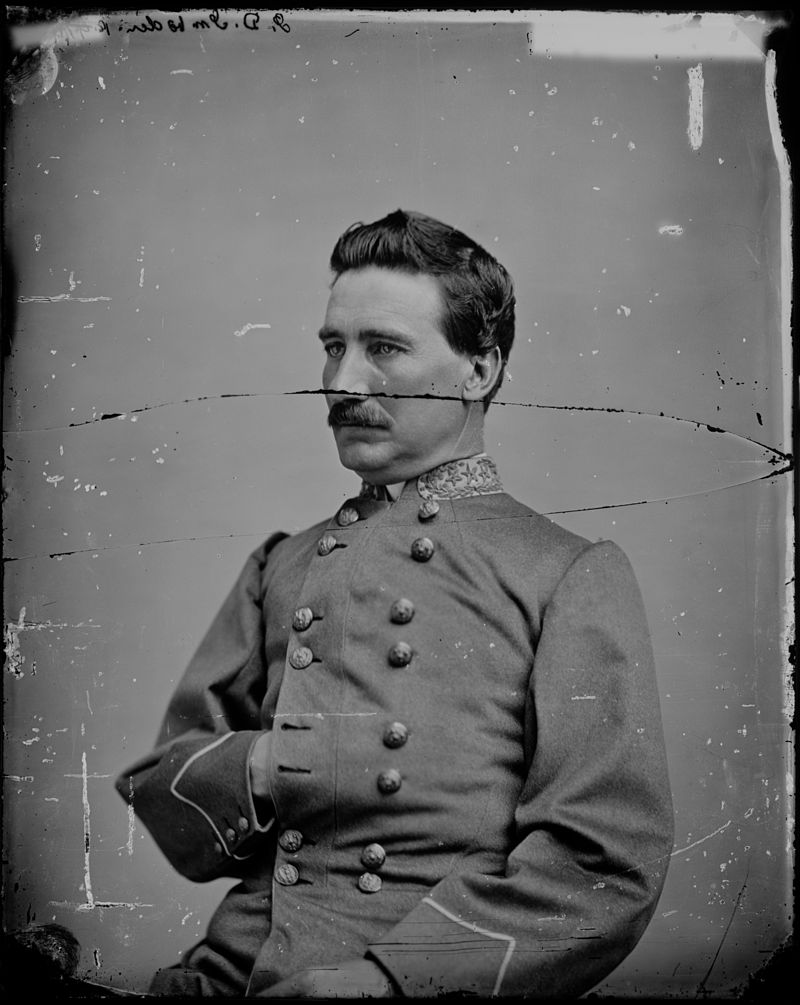

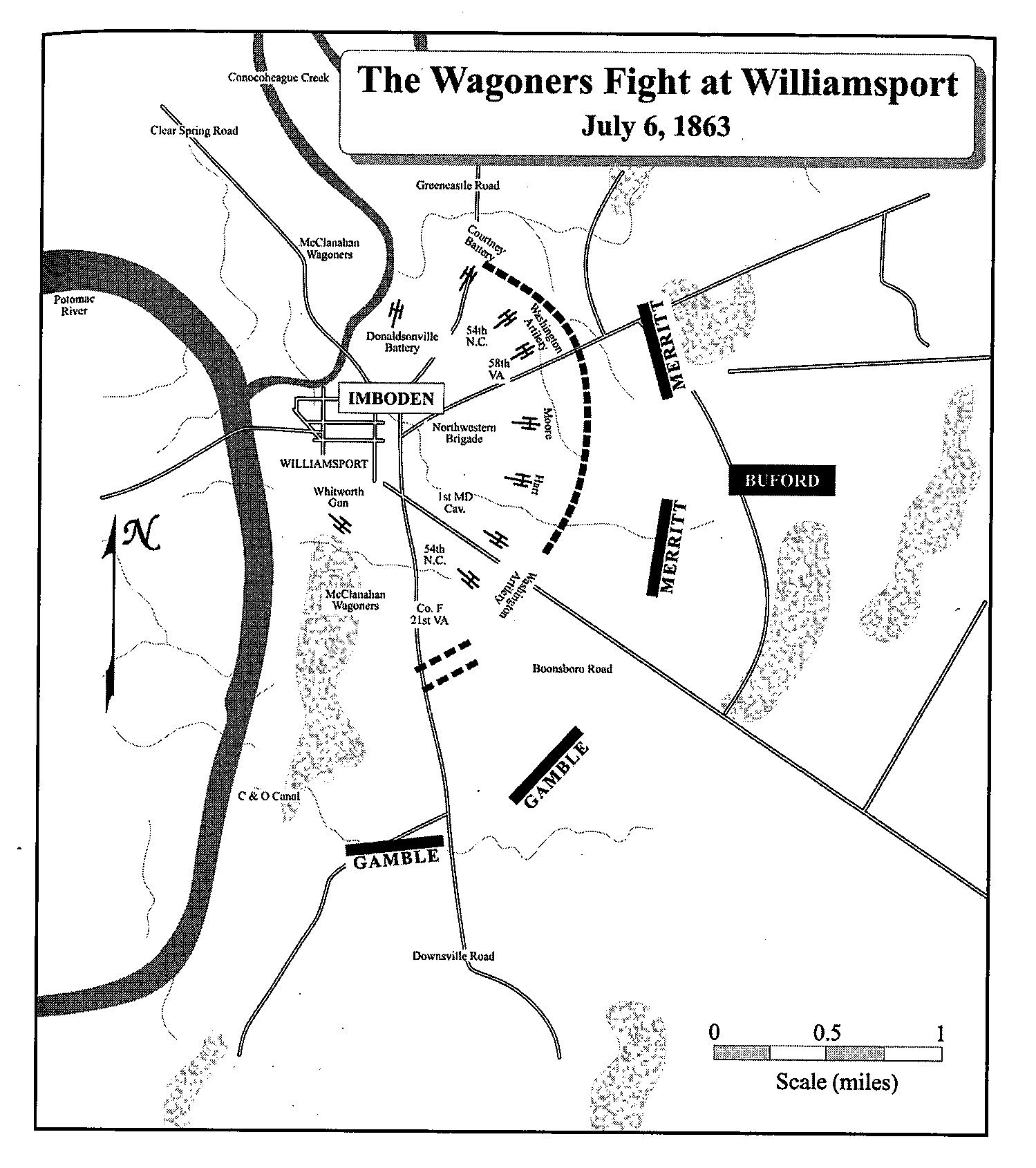

And so Imboden’s men and their wagons remained on the Maryland side of the Potomac, waiting for the other trains and their infantry comrades to arrive and for the river to recede. The Southerners were not idle. Imboden, who knew his small force was vulnerable to attack, already was directing the construction of a defensive perimeter. By early afternoon on July 6, the well-planned line arched away from the river, to the east and around the town, for a distance of three miles. The same flooded river to the west of town that had trapped Imboden’s party would protect it from federal flanking maneuvers and attack from that direction. For now, with Confederate cavalry units busy parrying Union assaults elsewhere and unable to help, and the other wagon trains and infantry columns were not likely to arrive that day, the band of 3000 cavalry men and wagoners was on its own and preparing for the worst. And John Imboden, who to some seemed an unlikely match for the challenge at hand, was their commander. Before the war the Virginian was a career lawyer and a state legislator, but never a military man. He did have militia training prior to the war, however, and was commissioned in the army of the CSA as a captain in 1861. He first served as an artillery officer before switching to the cavalry, where he raised a battalion of “partisan ranger” irregulars and ascended to rank of Brigadier General. Stuart did not much like or trust Imboden due to his lack of formal military experience.[i]

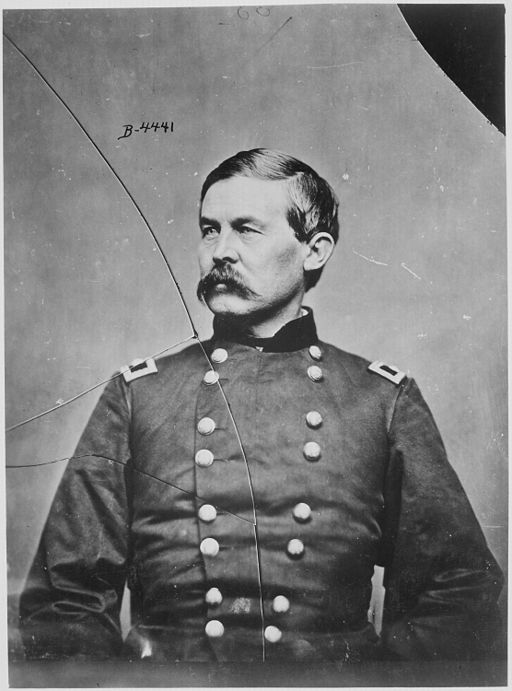

The Union attack occurred the afternoon of July 6 when a cavalry division under command of Brig. Gen. John Buford rode on Williamsport. Brig. Gen. Hugh Judson Kilpatrick and his cavalry troopers later appeared to join the fray, riding in from their failed attempt to force Stuart out of Hagerstown and occupy the strategic crossroads there (see Part 4 of this series). As he had done by successfully organizing, leading and defending his wounded men and their caravan to Williamsport, Imboden once again showed himself a practical and capable leader and proved Stuart’s opinion wrong.

Having heard the morning of July 6 of a potential Union cavalry attack, Imboden armed his wagon drivers, along with other non-combatants and the walking wounded, and dispersed them amongst his troops. He cleverly arranged and used some of his wagons for cover along his perimeter, and strategically placed his men and artillery, incorporating into the defensive line some of the high ground, bogs and wooded patches that surrounded the town. The stakes were very high. As the general recalled: “Every man in my command understood that if we did not repulse the enemy we should all be captured and General Lee’s Army be ruined by lack of transportation.”[ii]

When Buford appeared and attacked with his cavalry division that afternoon, to be joined later by Kilpatrick’s riders, Imboden’s men were ready. The fighting raged around Williamsport in a number of fierce exchanges along the town’s defensive lines. The general employed well his experience as an artillery officer and even used a bit of trickery to convince Burford’s men that they were attacking a substantial force, in his words, by “showing a formidable line on the left, then withdrawing it to fight on the right, together with our numerous artillery, 23 guns.”[iii]

Despite what Buford thought about his opponents’ numbers, Imboden’s mongrel mix of 3000 soldiers, wagon drivers, cooks and quartermasters still were badly outnumbered and knew they couldn’t hold on forever. Dramatically, a courier from Brig. Gen. W.H. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry division made it through the Union attackers with the following message: “Hold your own. We will be with you in half an hour.” The badly outnumbered defenders let out a cheer. Fitzhugh Lee’s men arrived and engaged both Burford and Kilpatrick’s forces. Night was approaching, and the federal riders withdrew to bivouac. Imboden, who later labeled the battle the “wagoners’ fight,” knew as well as anyone how vital Williamsport was to the Army of Northern Virginia and how close he and his men had come to losing it to their enemy. Years later he wrote: “A bold charge at any time before sunset would have broken our feeble lines, and then we should all have fallen easy prey to the Federals.”[iv]

On July 7, Robert E. Lee rode into Williamsport with a column of infantry, as did the rest of his army columns. The Potomac River still was too high to ford, the pontoon bridge destroyed and food and ammunition stores were limited. But his army still held the vital Potomac crossing points. The flooded river at their backs, Lee’s men expanded and strengthened existing defensive lines. Meanwhile his engineers began scavenging for the material needed to build another pontoon bridge across the river. Not about to go on the offensive, the Confederates dug in, waited, and wondered if the main force of the Army of the Potomac— which had recently started marching to Williamsport— would arrive, assemble and attack before the river receded and could be crossed.[v]

As he started travelling south from Gettysburg with his brigade on the same day Gen. Lee arrived in Williamsport, Lt. George Marden pondered the future as well. Later in the pursuit he learned that, for the present, the Army of Northern Virginia was trapped by the river and holed up in Williamsport. Eventually camped a handful of miles from the defensive works around Williamsport, the continuing bouts of rain seemed to guarantee that the water would not drop anytime soon. As the Sharpshooter theorized in a letter what might happen next, he reflected that— at the moment— time, rain and the flooded Potomac seemed powerful Union allies:

If the rebs have no facilities for crossing the river, every days delay is a gain to us. In fact I think we had best act simply on the defensive at this point… If they have got a strong position we had best leave them alone rather than lose 20,000 men in attempting to drive him out. We can afford to wait. They cannot. Before this [letter] reaches you the whole thing may be decided.[vi]

Marden was right to speculate that “the whole thing” regarding the Union army attacking versus Confederates escaping across the river might be decided before his letter was received. It would be, but not exactly in the Union’s favor. The rain and the river would turn out to be fickle allies.

To be continued…

END NOTES

[i] Richard F. Welch, Battle of Gettysburg Finale, “America’s Civil War” magazine, July 1994, re-published online at http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-gettysburg-finale.htm, Retrieved June, 10 2016; Tim Rowland Lee Escapes from Gettysburg, July 2014, “America’s Civil War” Republished online at http://www.historynet.com/lee-escapes-from-gettysburg.htm Retrieved June 30, 2016

[ii] Allen C. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (New York: Random House Vintage Civil War Library, 2014) 436; Brig. General John Imboden C.S.A., ed. John Miller, The Retreat from Gettysburg (1887), quoted on the Emmitsburg Area Historical Society website, http://www.emmitsburg.net/archive_list/articles/history/civil_war/imboden_memoirs.htm; Wittenberg et al, One Continuous Fight, 123-125, 139-140

[iii] Imboden, The Retreat from Gettysburg, http://www.emmitsburg.net/archive_list/articles/history/civil_war/imboden_memoirs.htm

[iv] Welch, Battle of Gettysburg Finale; Imboden, The Confederate Retreat From Gettysburg 3:428, quoted in Wittenberg et al, One Continuous Fight, 139

[v] Rowland Lee Escapes from Gettysburg; Welch, Battle of Gettysburg Finale; Guelzo, Gettysburg 436-437

[vi] George Augustus Marden, Civil War letters, July 13, 1863 (Courtesy of Rauner Library Special Collections, Dartmouth College, Hanover NH)

Interesting reading !

Thanks David! More posts on the retreat/pursuit to come.

Rob

Rob

My research to date has shown very little difference at high command levels between West Point men and others. Sometimes the West Pointers had such high expectations put on them that they were bound to disappoint, but there was certainly a lot of disappointment to go around. Again and again I read of men–North & South–who saw their appointment to the military academy as a sure way to be able to skip a few social steps in the ascent to the top of the social ladder (I guess Grant is the exception that “proves” the rule–lol). Rarely do they mention their duty to country, or anything else very patriotic.

It is interesting to see that the officers who were political or social appointees did as well as those who were professionally trained, and several Northern officers continued to be involved in Union building after the war–Sickles, Howard, to name two.

I never thought to consider John Imboden as anything other than a talented and honorable officer. Stuart? Sometimes his glowing silver armor looks a little tarnished in places.

Dear Mr. Wilson: I take umbrage at your choice of words in the second paragraph above. Your use of the words “a band of Yankee marauders” is not factually correct. The Union military force sent to Williamsport to destroy the pontoon bridge was under direct orders from Major General William H. French at Harpers Ferry. Based on a strong intelligence report from Colonel Andrew McReynolds, commander of his cavalry brigade, General French approved a plan to destroy the pontoon bridge at Williamsport and issued orders to do that on July 3. Major Shadrach Foley was chosen to command a special force of cavalry of about 300 troopers, composed primarily from his own 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, with others from the 1st New York Cavalry, 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and 1st W.Va Cavalry. Major Foley and his men left Frederick at dusk on July 3, passed through Boonsboro, and arrived at their objective before dawn on July 4. They dismantled and destroyed the pontoon bridge as ordered, surprised and captured a small Confederate force nearby at Falling Waters, and destroyed Confederate ammunition, supplies, and equipment. With the threat of rain and approaching daylight, Major Foley and his command withdrew and headed back to Frederick-not one officer or trooper was injured or lost in the mission to Williamsport. This was a tactical military decision made by Major General French, with a military objective and with command-and-control in place from beginning to end. In no way can the men of this cavalry force be described as “a band of marauders” (plunderers). I am afraid your Confederate slip is showing, Mr. Wilson.

Dear Miriam: My choice of the word “marauders” to describe the federal cavalrymen who attacked and destroyed the pontoon bridges was a poor one. I didn’t mean to convey that they were acting as privateers. I intended to describe them as “attackers,” and I see that “marauder” has that more negative connotation, of acting outside of the law or military rules of engagement. I am well aware they were, in fact, conducting a military operation. And I see that my poor choice of words could convey that they were not. Thanks for pointing that out.

Rob Wilson

Where are parts 374???

This should read 3&$, was frustrated trying to post a comment.