Charge On: Re-examining Civil War Cavalry Tactics

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome guest author Bill Backus

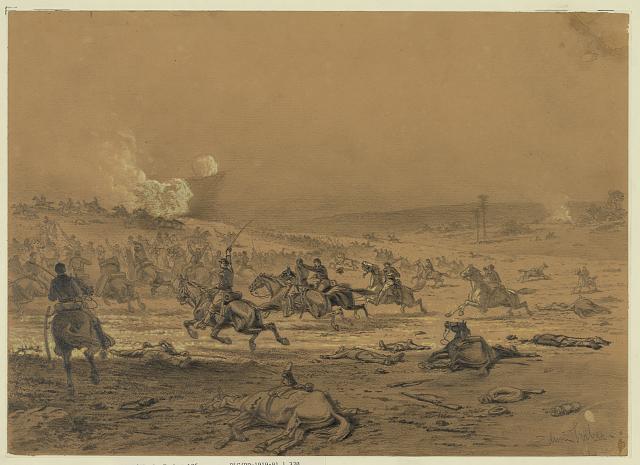

A popular misconception of the American Civil War is the view that mounted charges against infantry were an outdated tactic. The image of charges being ordered by out-of-touch generals that did not comprehend that rifled muskets had changed combat is a common one. While the Civil War produced many instances of cavalry charges that failed against infantry, these have been sometimes overemphasized by historians as an argument for the effectiveness of the rifled musket. By examining the actions of Federal cavalry mainly associated with the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, a more nuanced view of cavalry charges emerges.

Perhaps two of the most widely known cavalry charges against infantry are the 5th U.S. Cavalry charge at Gaines Mill and the Farnsworth Charge at Gettysburg. Both charges ended in failure and both have been used by historians as examples of outdated tactics that caused unnecessary casualties. While the emphasis on the cause of the failure has usually been the fire coming from rifled muskets, both charges got well within 100 yards before being repulsed, well within the range of smoothbore muskets. The main reason that both charges failed is not from the use of rifled muskets (again smoothbore muskets would have easily repulse these charges, and in fact some of the Confederates that threw back these assaults were still armed with smoothbore muskets), but that the infantry was alert and ready for the charge.

When infantrymen were not ready to receive an assault, a small cavalry charge could be temporarily successful, as was the case of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry at Cedar Mountain. Towards the end of the battle, one squadron (2 companies) of Pennsylvanians were ordered to charge a battery that was captured by surging Confederates. Thundering down the Culpepper Road, the blue clad horsemen were able to break the Confederate line. However, since the Federals were outnumbered, they were quickly sent galloping back the way they came. The failure of this charge was not from the effectiveness of the rifled musket, but because of the small number of cavalrymen that were sent into the charge. Three examples of Federal cavalry charges during the last year of the war show that mounted charges could be successful, even decisive, if enough troopers were engaged.

By 1864, the Federal cavalry in Virginia was nearing the pinnacle of power. Not only were the majority of the troopers veterans armed with modern weapons (including the Spencer carbine) but more importantly the majority of officers all the way up through the chain of command were prepared by experience and temperament on how to effectively use cavalry. At the end of the Third Battle of Winchester in September 1864, a couple divisions of Federal cavalry were thrown against the left of the Confederate line at exactly the right time to help rout the rebel army from the field of battle. A few weeks later in the Shenandoah Valley at the Battle of Cedar Creek, Federal cavalry again decisively aided in the rout of a Confederate army by a mounted charge against both flanks of the rebels.

In the final week of the war at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, a mounted charge by Federal cavalry against partially entrenched Confederate infantry not only succeeded, but steamrolled over the rebels capturing many prisoners and making the rest combat ineffective for the rest of the campaign. Although many Confederates were demoralized during the Appomattox Campaign, low morale was not the primary reason for the success of the mounted charge. On other parts of the battlefield, Confederate infantrymen were not only able to stop a Federal infantry attack, but launch their own counterattack that was finally thrown back after heavy casualties. Later in the campaign closer to Appomattox Courthouse, portions of Lee’s army still showed a willingness to engage the enemy.

If mounted assaults could be decisive, as was the case during the last year of the war, why weren’t more charges successful? While rifled muskets could damage a cavalry charge the success and failure of a charge boiled down to two factors. First, the cavalry had to be used at the right time. Against infantrymen who were organized and still had their morale, a mounted charge often was little more than an exercise in organized suicide, such as Farnsworth’s Charge or the charge at Gaines Mill. Secondly, once the cavalry was engaged, they had to be used in adequate numbers to keep the momentum and prevent the infantrymen from rallying. A perfect example is the 1st Pennsylvania at Cedar Mountain; even though the troopers broke through the rebel line, there were not enough of them to keep the Confederates from rallying and throwing them back. A cavalry charge was a one-shot weapon and its success depended on the commander knowing when to commit the charge at the decisive point at the decisive time. By 1864, Federal cavalry was finally concentrated in sufficient numbers and commanded by men who knew when and where to mount a charge. The results were multiple cavalry charges that were wildly effective against veteran infantrymen equipped with rifled muskets.

Bill:

Great post.

Phil Sheridan was a passionate advocate for the power of cavalry. His success in the Shenandoah and Appomattox campaigns are proof of his wisdom.

I would add one major battle to your excellent list where cavalry played a key role – Nashville. George Thomas and his cavalry commander, James Wilson, showed that a large, concentrated unit of cavalry could play an important part in flanking movements, just like Sheridan did in the Shenandoah and Appomattox campaigns.

And Wilson’s raid – with some 13,000 troopers – through Mississippi in the waning days of the CW proved cavalry can destroy an opponent’s war-making infrastructure, too. As a side benefit, Wilson’s horsemen later captured a fleeing Jefferson Davis.

Too bad it took the Union command three years to learn to concentrate horsemen in enough numbers to be decisive.

While I would agree with most of your post, I would also add that the rifle did have some significant impact. In the smoothbore era, Infantry felt the need to revert to squares as the standard defense against cavalry. Even troops in line could be ridden down and flanked – it happened repeatedly.

In the rifled era (and we do have some examples of contemporary European conflict, mainly in Italy in 1859) squares were considered unnecessary. The rifle’s greater range tended to disrupt cavalry sufficiently to disrupt mounted formations enough that lines could more effectively win the “showdown” between mounted and foot.

But the key to any successful charge, of almost any era, was always timing. Hitting a disrupted, disorganized, or distracted foe was the key factor in a successful charge – not the weapons. By 1864, the Federals were getting to be masters of that timing.

Thanks for the reply!

I recently came across another form of defense against cavalry in addition to the traditional square. At the end Battle of Bull Run Bridge near Manassas, Virginia on August 27, 1862 Confederate cavalry attempted to cut off retreating Federal soldiers. Major William Henry Jr. of the 1st New Jersey Infantry ordered his regiment to “column against cavalry to be formed, and the brigade [1st New Jersey Brigade] marched in good order to the rear. In the execution of this order, accomplished by a rapid movement, the principal part of our loss was sustained.” OR Series I, Vol 12, page 539.

According to Hardee’s Manuel:

“Column against cavalry.

965. When a column closed in mass has to form square, it will begin by taking company distance; but if so suddenly threatened by cavalry as not to allow time for this disposition, it will be formed in the following manner:

966. The colonel will command:

1.Column against cavalry. 2. MARCH.

967. At the first command, the chief of the leading division will caution it to stand fast and pass behind the rear

rank; in the interior divisions each captain will promptly designate the number of files necessary to close the interval between his company and the one in front of it. The captains of the divisions next to the one in rear, in addition to closing the interval in front, will also close up the interval which separates this division from the last; the chief of the fourth division will caution it to face about, and its file closers will pass briskly before the front rank.

968. At the command march, the guides of each division will place themselves rapidly in the line of file closers. The first division will stand fast, the fourth will face about, the outer file of each of these divisions will then face outwards; in the other divisions the files designated for closing the intervals will form to the right and left into line, but in the division next to the rearmost one, the first files that come into line will close to the right or left until they join the rear division.”

I don’t know if column against cavalry was around in manuals during the smoothbore era or is yet another example of the rifle musket forcing military officers on both sides of the Atlantic to innovate.

Hi Bill,

Good subject and good post.

In the cavalry tactics of the time, if they weren’t supporting artillery or guarding the flanks, the cavalry was supposed to be prepared to charge with overwhelming force if the enemy’s infantry broke. Cedar Creek exemplifies this, with the federal cavalry advancing on the flanks and then charging wildly down the Pike past Strasburg when the Confederate infantry broke.

You’re talking about an elaboration on the tactics taught at West Point or to volunteer officers. The 1st Pennsylvania charge at Cedar Mountain was actually made by a battalion (two squadrons) but before it wheeled only the first squadron came in contact with the Confederate infantry due to the normal spacing of cavalry columns. No artillery had been captured, but Banks’s staff feared that the reforming Confederate infantry would soon overrun the batteries and sent the cavalry to blunt the advance. I guess you could say it was successful since the infantry assault didn’t happen, but it was a forlorn hope mission. I’m not sure what Kilpatrick was thinking, but Farnsworth’s charge seems like an equally forlorn mission.

Other occasions in the AoP when cavalry overran infantry, even behind breastworks, were Falling Waters in July 1863 and Five Forks in April 1865. The timing of the charges was right, and one might argue that the Confederate infantry was in withdrawal mode in both of those engagements. Regarding rifled weapons, the speed of cavalry limits the benefit of long-distance weaponry in muzzle-loading rifles. As we found in our dash at Cedar Mountain, a gallop gives the infantry one shot on the approach and maybe one more if the charge is diverted. Terrain and dust kept the 1st Pennsylvania obscured until about the point where we began our gallop. A volley from infantry behind the fence on the left leveled many horses and riders, and the infantry in the trees ahead finished the job. Smoothbores would have been equally lethal at that range. And isn’t it ironic that the “obsolete” saber remained a potent weapon against both cavalry and infantry (and artillery) until the end of the war?

Great post that further undermines the assumption that the rifled musket “revolutionized” the battlefield. Cavalry alone could not defeat steady infantry, whether it was at Minden or Waterloo. Rifled muskets had only a marginal effect.

Another thing to keep in mind with successful cavalry charges was combined arms, where infantry, cavalry, and artillery were used in the attack. Combined arms required excellent officers and well trained troops, but it is no coincidence that the most successful generals of the era, such as Marlborough, Frederick II, and Napoleon, made use of this tactic.

But it is exactly on that “margin” that the greater range (expanded kill zone) comes to have the effect of diminishing the power of the charge before it makes physical sabre to flesh contact with the infrantry unity being charged. Regrettably the post just makes bald faced assertions and does not provide logic or evidence to support the claims made.

There’s also the Mississippi Rifles at Buena Vista.