Baseball In The Blue And Gray (Part 1)

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back guest author Michael Aubrecht

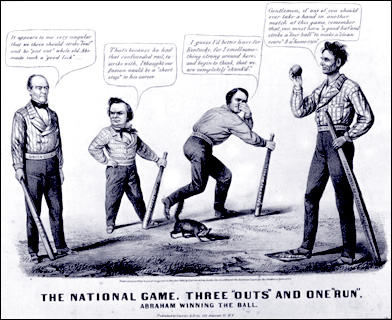

It is considered America’s National Pastime, but far more than just a mere sporting event, baseball has become a major part of the American consciousness. During war, following natural disaster, or in the midst of economic hardship, this game has always provided an emotional escape for people from every race, religion and background who can collectively find solace at the ballpark. Therefore, it somehow seems fitting that the origins of modern baseball can be traced back to a divided America, when the country was in the midst of a great Civil War. Despite the political and social grievances that resulted in the separation of the North and South, both sides shared some common interests, such as playing baseball.

During the War Between the States, countless baseball games, originally known as “Town Ball,” were organized in army camps and prisons on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. Although these early forms of baseball had already become high society’s pastime years before the first shots of the Civil War erupted at Fort Sumter, it was the mass participation of everyday soldiers that helped spread the game’s popularity across the nation. In his 1911 history of baseball titled America’s National Game, Albert G. Spalding wrote, “Modern baseball had been born in the brain of an American soldier. It received its baptism in the bloody days of our Nation’s direst danger. It had its early evolution when soldiers, North and South, were striving to forget their foes by cultivating, through this grand game, fraternal friendship with comrades in arms.”

He added, “No human mind may measure the blessings conferred by the game of Base Ball on the soldiers of our Civil War. It calmed the restless spirits of men who, after four years of bitter strife, found themselves at once in a monotonous era, with nothing at all to do.”

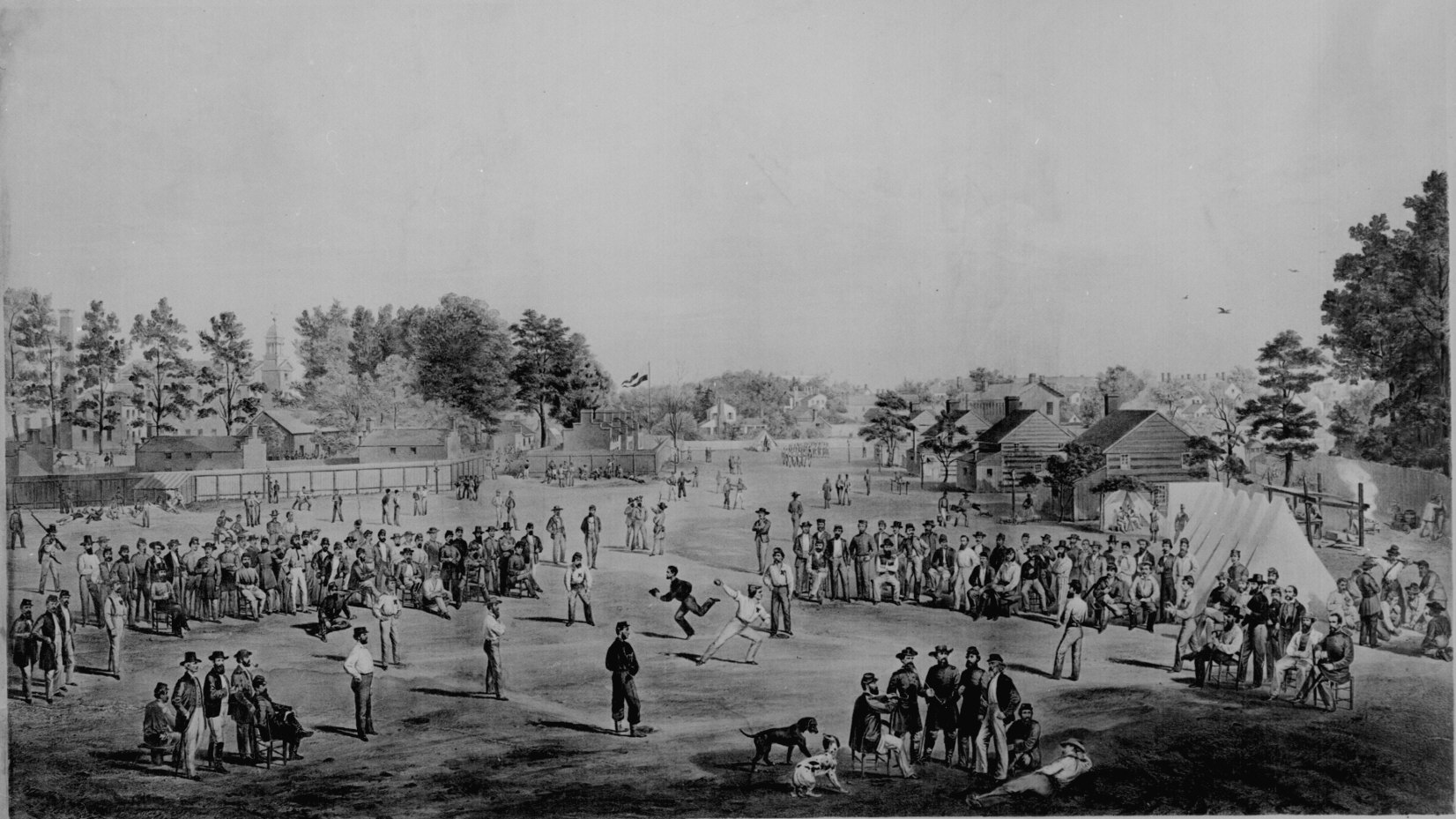

Very little documentation exists regarding these games and most information has been derived from letters written by officers and enlisted men to their families on the home front. Of the hundreds of pictures taken during the Civil War by photographers, there is only one photo in the National Archives that clearly captured a baseball game underway in the background. The image was taken at Fort Pulaski, Georgia and shows the “original” New York Yankees of the 48th Volunteers, playing a game in the fortification’s yard.

Several newspaper artists also depicted primitive ballgames and other forms of recreation devised to help boost troop morale and maintain physical fitness. Regardless of the lack of “media coverage,” military historians have proven that baseball was a common ground in a country divided and helped both Union and Confederate soldiers temporarily escape the horror of war.

“Town Ball” is a direct descendant of the British game of “Rounders.” It was played in the United States as far back as the early 1800s and is considered a steppingstone toward modern baseball. Often referred to as “The Massachusetts Game,” it is still played by the Leatherstocking Base Ball Club every Sunday in Cooperstown. According to the game’s official rules as published by The Massachusetts Association of Base Ball Players, May 13, 1858: “Basetenders (infielders) and scouts (outfielders) recorded outs by plugging or soaking runners—a term used to describe hitting the runner (tagging them did not count) with the ball.”

Some additional “Town Ball” rules that are similar to today’s standard “Baseball” game include: “The Ball being struck at three times and missed, and caught each time by a player on the opposite side, the Striker shall be considered out. Or, if the Ball be ticked or knocked, and caught on the opposite side, the Striker shall be considered out. But if the ball is not caught after being struck at three times, it shall be considered a knock, and the Striker obliged to run. Should the Striker stand at the Bat without striking at good balls thrown repeatedly at him, for the apparent purpose of delaying the game, or of giving advantage to players, the referees, after warning him, shall call one strike, and if he persists in such action, two and three strikes; when three strikes are called, he shall be subject to the same rules as if he struck at three fair balls.”

Army encampments were not the only locations to host “Town Ball” games. Prisons also held them as POWs struggled to escape the hopelessness of their situation and combat the mind-numbing boredom that confronted them each day. One such institution was Salisbury Prison, located in North Carolina. The compound was established on sixteen acres purchased by the Confederate Government on November 2, 1861. The prison consisted of an old cotton factory building measuring 90×50 feet, six brick tenements, a large house, a smith shop and a few other small buildings.

Although a primitive form of baseball was somewhat popular in larger communities on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line, it did not achieve widespread popularity until after the start of the war. The mass concentration of young men in army camps and prisons eventually converted the sport formerly reserved for “gentlemen” into a recreational pastime that could be enjoyed by people from all backgrounds. For instance, both officers and enlisted men played side by side and soldiers earned their places on the team because of their athletic talents, not their military rank or social standing.

Both Union and Confederate officers endorsed baseball as a much-needed morale builder that also provided both mental and physical conditioning. After long details at camp, it eased the boredom and created a team spirit among the men. Some soldiers actually took baseball equipment to war with them. When proper equipment was not available they often improvised with fence posts, barrel staves or tree branches for bats and yarn or rag-wrapped walnuts or lumps of cork for balls.

The benefits of playing while at war went far beyond fitness, as often the camaraderie displayed on the baseball diamond translated into a teamwork mentality on the battlefield. Many times, soldiers would write of these games in the letters sent home, as they were much more pleasant to recall than the hardship of battle. This was perhaps one of the earliest forms of sports journalism and the precursor to the “box-score beat writers” of the 20th century.

Private Alpheris B. Parker of the 10th Massachusetts wrote, “The parade ground has been a busy place for a week or so past, ball-playing having become a mania in camp. Officers and men forget, for a time, the differences in rank and indulge in the invigorating sport with a schoolboy’s ardor.”

Another private writing home from Virginia recalled, “It is astonishing how indifferent a person can become to danger. The report of musketry is heard but a very little distance from us . . . yet over there on the other side of the road most of our company, playing bat ball and perhaps in less than half an hour, they may be called to play a Ball game of a more serious nature.”

Sometimes games would be interrupted by the call of battle. George Putnam, a Union soldier, humorously wrote of a game that was “called-early” due to the surprise attack on their camp by Confederate infantry: “Suddenly there was a scattering of fire, which three outfielders caught the brunt; the centerfield was hit and was captured, left and right field managed to get back to our lines. The attack . . . was repelled without serious difficulty, but we had lost not only our centerfielder, but . . . the only baseball in Alexandria, Texas.”

Michael Aubrecht is an author, as well as a Civil War Historian. He has written several books including The Civil War in Spotsylvania and Historic Churches of Fredericksburg. Michael was also a contributing writer for Baseball-Almanac from 2000-2006. He lives in historic Fredericksburg. Visit his blog online at https://maubrecht.wordpress.com/.

SOURCES:

George B. Kirsch, Baseball in Blue & Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003)

George B. Kirsch, “Bats, Balls and Bullets: Baseball and the Civil War,” Civil War Times Illustrated, Vol. XXXVI, No. 2, (Harrisburg, PA, May 1998)

Harvey Frommer, Primitive Baseball: The First Quarter Century of the National Pastime (Atheneum; 1st edition, April 1998)

J.G. Adams, Reminiscences of the 19th Massachusetts Regiment (Boston: Wright and Porter, 1899).

Michael A. Aubrecht, Baseball and the Blue and Gray (Baseball-Almanac: Pinstripe Press, 2004)

Patricia Millen, From Pastime to Passion: Baseball and the Civil War (Heritage Books, January 2001).

I have written about this so many times–it is a topic I love dearly! It is wonderful to see so many reenactors include a ball game in the mix of the weekend activities, and watching teams play old time baseball is a treat as well. When we were in Wisconsin, we made sure to hit the sights where “League of Their Own” was filmed.

If anyone ever has a chance, google up “old-time baseball” and see if you have a league near you. Our area just added a new team from San Jose to the schedule this year. Huzzah!