1860’s Politics: “Like a Burning Bush”: Jefferson County, (West) Virginia’s First Postwar Election(s)

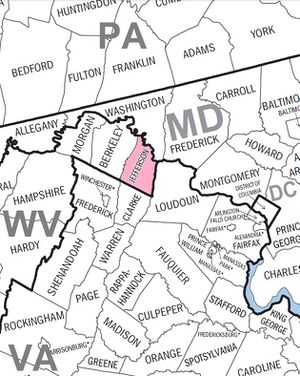

Still to this day, despite the issue supposedly being settled by the Supreme Court 145 years ago, the debate lingers among some–should Jefferson County be in Virginia or West Virginia?

Still to this day, despite the issue supposedly being settled by the Supreme Court 145 years ago, the debate lingers among some–should Jefferson County be in Virginia or West Virginia?

Look at a modern map, and you’ll clearly find the county is the easternmost county in West Virginia. But that has not silenced the doubters, and the decisions made in the politically charged climate of the 1860s still are questioned to this very day.

Jefferson County began the Civil War in one state and ended it in another. It was prosperous in 1860; of the ten counties in the Shenandoah Valley, its output of wheat ranked at the top. Twenty-seven percent of its population was enslaved, and it seemed as if the county had put the scare of John Brown’s Raid from the forefront of its mind. Constitutional Unionist John Bell won the county by a 2 to 1 margin in the 1860 Election, in which 1,857 people voted. Virginia’s secession brought change to Jefferson County, particularly when a secession movement from seceded Virginia began in 1861.

During the discussions that eventually resulted in the establishment of West Virginia, the Eastern Panhandle counties (of which Jefferson was one) were to be given a vote to accept or not accept the constitution adopted by Virginia’s loyal government (the precursor to West Virginia). The date was to be April 3, 1862, but turmoil in Jefferson County prevented the vote from taking place. Jefferson County held its election on May 28, 1863, in which only 250 people voted (compared to 1,857 in the Election of 1860). No effort was made to give voters notice of the election, an oath of allegiance to the United States was required to vote, and, under military rule, few citizens could travel to the two obscure polling places of Harpers Ferry and Shepherdstown. Only two voted against the proposed constitution, and on November 2, 1863, Jefferson County officially became a part of the new state of West Virginia, carrying with it the important Baltimore & Ohio Railroad into a Union state.

When the Civil War ended and what remained of Jefferson County’s prewar, predominantly southern-leaning population returned home, they felt uneasy about the situation they now found themselves in. Much of the county was in ruins, the county seat moved, and homes destroyed.

One Charlestown (the former county seat as of 1865) Unionist captured the political climate of that piece of conservative Jefferson County best:

They are all Rebels here,–all Rebels! They are a pitiably poverty-stricken set; there is no money in the place, and scarcely anything to eat. We have for breakfast salt-fish, fried potatoes, and treason. Fried potatoes, salt-fish, and treason for dinner. At supper the fare is slightly varied, and we have treason, salt-fish, fried potatoes, and a little more treason. My landlady’s daughter is Southern fire incarnate.

Then, sticking with the theme of fire, he concluded: “The war-feeling here is like a burning bush with a wet blanket wrapped around it. Looked at from the outside, the fire seems quenched. But just peep under the blanket, and there it is, all alive and eating, eating in.”

Clearly, not everyone in the county approved of the move, and they very much smelled a rat in the process. Basing their claims on the fact that Congress’s act naming West Virginia a state did not specifically mention Jefferson County and its neighbor to the west, Berkeley, detractors argued that the transfer of the two counties never happened and was illegal. Virginia claimed the counties as part of its Seventh Congressional District.

The detractors met in Charlestown on September 2, 1865 to appoint delegates to the convention for Virginia’s Seventh District. The election date was set for October 12. West Virginia Governor Arthur Boreman thwarted the election by threatening the arrest of anyone involved in it and sent Federal troops to the county to stop the election before it could take place.

An election for delegates to West Virginia’s governing body did take place on October 28, 1865. But the means used to procure the Radicals’ desired results were all too familiar to Jefferson Countians. Votes were thrown out individually or, in one case, one entire district’s votes were discounted in order to keep authority of the county in the Radicals’ hands. Elections continued like this for some time.

Not to be outdone, the county’s conservatives called a second meeting in Charlestown several weeks after the election. The meeting’s purpose was to draft petitions to be sent to the U.S. Congress and the Virginia General Assembly that pleaded for Jefferson County to be returned to Virginia. Over 1,200 people signed the petitions.

In 1867, Virginia took West Virginia to the Supreme Court over this disagreement. In the midst of the case being heard, one of the Court’s nine justices died, and left the vote deadlocked at four a piece. This stalemate lasted until 1871, when the case was presented again to the Supreme Court, and on March 6, 1871, West Virginia won the case–and the counties–by a vote of 6 to 3.

Today’s elections in Jefferson County are far from being so lopsided and unjust as that first election after the war in October 1865. But the question and the debate have never quite died, even as recent as 2011. Some habits just die hard.

Jefferson County gets no extra sympathy from me. Eight counties in West Virginia never voted at all in any Pierpont election but were still included in the new state and they were just as supportive of Virginia as Jefferson County. Union soldiers were voting in all the elections and their votes included in the totals as citizens. Almost the total vote in Cabell County for the state constitution in 1862 were by non-resident soldiers. So I don’t think we need to exceptionalize Jefferson County when the entire scheme was a sham.