“I Would Rather Be Shot Myself” – Reactions to an Execution, December 1861

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome guest author Jake Wynn

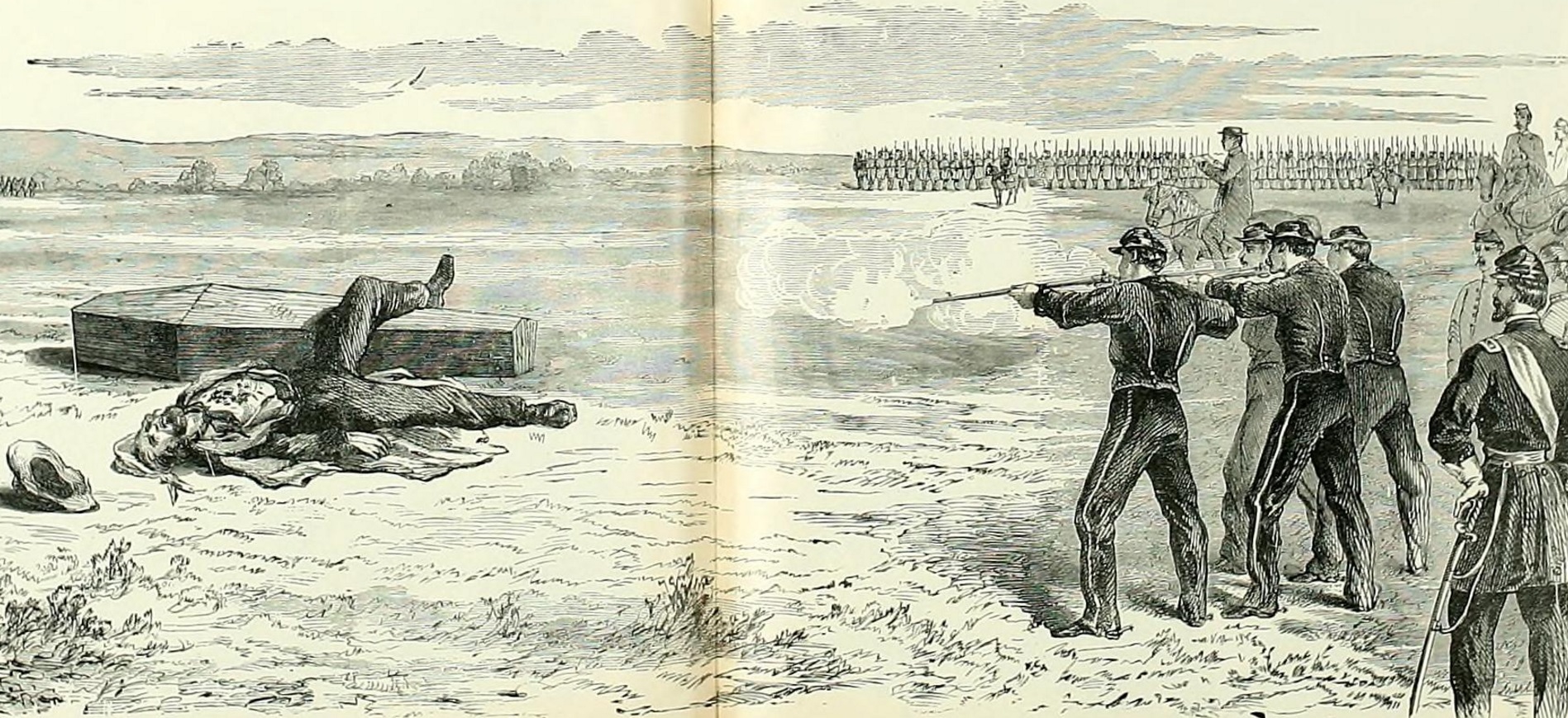

Assembled in a field near the Fairfax Seminary just beyond Alexandria, Virginia, an entire division of 10,000 soldiers stood in a hollow square with one side missing. At the center stood twelve men, muskets at the ready. Ahead of them sat 23-year-old Private William H. Johnson atop a coffin with a white handkerchief tied over his eyes. The drums rolled and the order to fire was given. A volley of eight muskets landed home in Private Johnson’s chest.

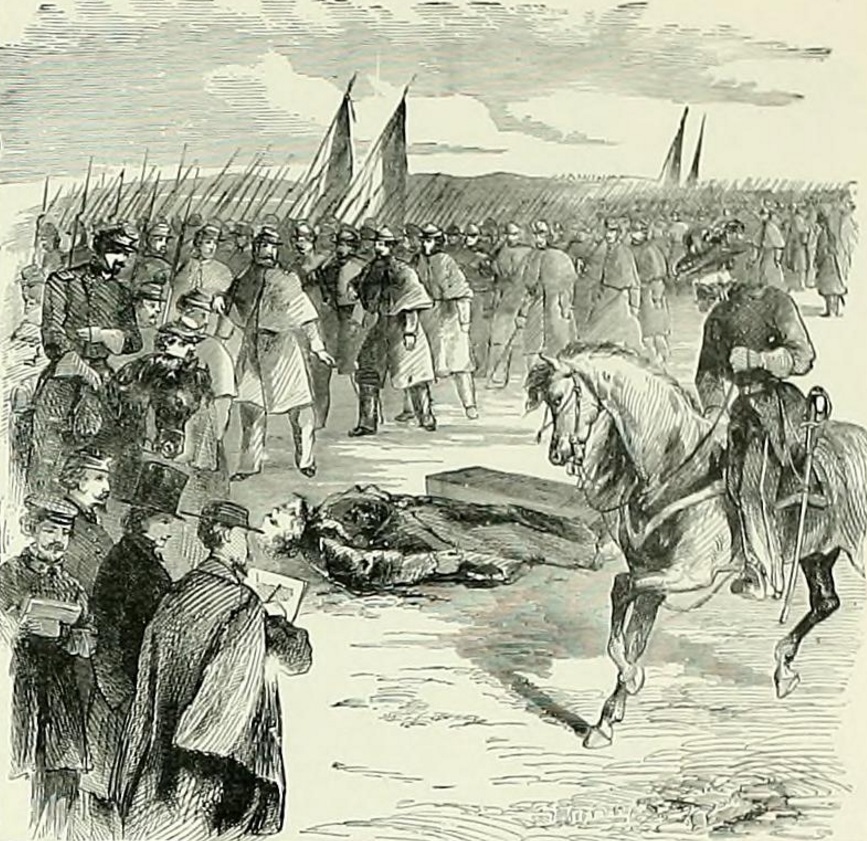

“He sat on the coffin about four seconds after they had fired,” wrote Corporal Henry Keiser of the 96th Pennsylvania, “and then fell backward over it.” A reserve group of four stepped forward and put a final volley into the young deserter’s body at close range, ensuring life had been extinguished. Captain Peter Filbert checked his watch; it was 3:41 in the afternoon, December 13, 1861.

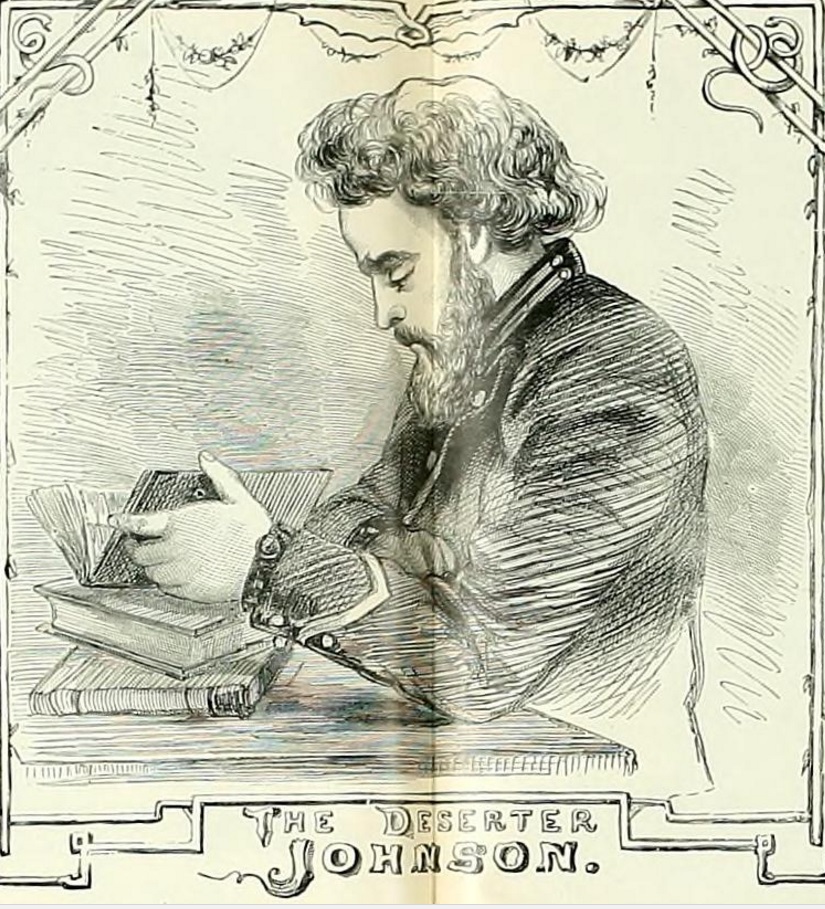

Moments earlier, Private Johnson had muttered his final words: “Boys,—I ask forgiveness from Almighty God and from my fellow-men for what I have done. I did not know what I was doing. May God forgive me, and may the Almighty keep all of you from all such sin!” Johnson had been found a few days earlier attempting to pass into Confederate lines.

Among the units collected for the purposes of witnessing this execution were the rowdy men and boys of the 96th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Assembled in the hard-scrabble coal fields of eastern Pennsylvania, the 96th had yet to see the realities of military service. The price Private Johnson paid was the cost of enforcing military discipline in the Army of the Potomac.

The reactions within the ranks of the 96th Pennsylvania varied distinctly.

“Last Friday I witnessed what I never did before and what I have no particular desire to see again: the Execution of a soldier belonging to our division,” wrote Assistant Surgeon Washington Nugent in a letter to his wife. “I assure [you] it was a sad and solemn sight to see a poor mortal sent so hurriedly into Eternity.”

Private Clement Potts of Company A was similarly disturbed by the sight of this butchery. “It was the most horrible sight I ever seen [sic]. It was the first time that I ever seen a man shot and hope the last,” Private Potts said. He and his comrades were to see this butchery repeated on a grand scale in a few months’ time on the Virginia Peninsula.

Despite the obvious distaste in witnessing the death of a fellow man, officers could see the good in this sort of stark discipline. Dr. Nugent recorded, shortly after voicing his distaste for the whole affair, that “he richly deserved his fate and his Execution I have no doubt will have a salutary effect upon our soldiery.”

The regiment’s Adjutant M. Edgar Richards agree with that sentiment. “There was very little pity felt for him in this Division on account of the atrocious character of his crime,” Richards wrote in a letter to his father at home in Pennsylvania. Yet Richards also felt lucky that his duties as regimental adjutant had kept him away from the regiment on December 13, and he missed the entire affair. “I was glad my duty in Washington prevented my being with my [regiment] at the execution.”

The division was marched, regiment by regiment, passed the corpse of Private Johnson laying draped over his coffin. Corporal Keiser of Company G described the bloody scene. “I seen one hole in his forehead above the left eye, one in the mouth and four in his breast,” Keiser noted in his diary. The 96th filed past and then returned to their encampment.

For the medical officers of the regiment, their dealings with Private Johnson did not end there. Surgeon Nugent noted in the letter to his wife that he and the regimental surgeon, Dr. Daniel Webster Bland, received notice from their Brigade Surgeon that there was to be a post-mortem examination of the body.

Nugent and Bland walked from their encampment to the brigade hospital a mile and half away from their encampment at 9 o’clock that evening. “We met about thirty medical men and made some very pleasant acquaintances,” wrote Dr. Nugent. But their main reason for being in the hospital that evening was the autopsy of Private Johnson. At a moment early in the conflict when many medical personnel had yet to see the results of gunshot injuries, this was a teachable moment.

Dr. Nugent and the other surgeons in the room opened the examination by observing the path of each ball through the subject’s chest. “At the fire four balls entered the chest, two in front of the chest, one in the side, one at the upper end of the breast bone,” Nugent said. He also noted the destruction that the bullets did to the heart and other organs. Then, they examined the destructive head wounds caused by the second volley.

These moments in the wake of the execution gave novice Army surgeons a preview of the injuries they may experience once they headed onto the battlefield with the Army of the Potomac.

As for the regiment, this surely marked a low point in the unit’s early service. Rumors spread in the weeks after the Johnson execution that there were to be similar proceedings to come. The whole affair seemed to haunt the unit for days afterward. Private Potts mused over the events of December 13, 1861 in a letter to his brother.

“I would rather be shot myself than to shoot another man,” he wrote.

Jake Wynn is a 2015 graduate of Hood College, and is currently the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. He also writes independently at his own blog, Wynning History.

Excellent article… I felt like I was there.

i agree with Doug well written thank you