The Straight Poop: Pushing Interpretive Boundaries

If you follow Civil War Trails on Facebook you may have seen a recent post about poop. Yes. It’s true. I hesitated making the initial post for a few days. I even checked with some of my board members to make sure I wasn’t crossing a line and that my job would be intact after such a decision. So, why did I overthink it then, and why, despite my hesitation, did I bring it up again here?

As signs on the Trails network need maintenance, John Salmon (our historian) and I review the text, photos, and even the sign’s location to ensure we are putting out the best possible information. We will look high and low for a citation, better media, and evocative quotes, often uncovering “new” primary source material squirreled away in local repositories. That’s the fun part of our job and puts us in touch with more ideas, sources, stories, and photos than we could possibly incorporate into a single sign.

Such was the case in Frederick County, Maryland, with a sign titled, “Carrollton Manor, the green corn march,” part of the Antietam Campaign trail.

The text described Confederate soldiers stripping the adjacent fields of unripe corn, which caused “stomachaches.” The text also described the gift of a horse to Stonewall Jackson from a local farmer. According to Henry Kyd Douglass, it was this horse that summarily threw Jackson, resulting in his ambulance ride.

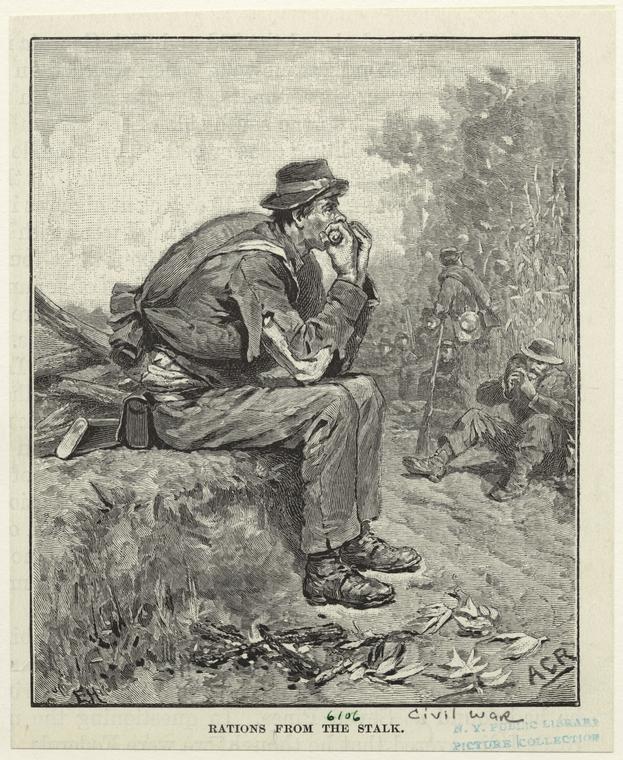

The two images and a map that accompanied the text were good, but we decided to use this image by Allen Christian Redwood in place of one extant photo. It was a better depiction of Lee’s soldiers on the march in their tattered uniforms, lunching on the corn, and was even drawn by someone who was there—it doesn’t get better than that.

“Stomachaches” was the least we could say about the effects of green corn on the human digestive tract. It left a little something to the imagination and was decidedly rated “G.” However, in the back of my mind, I knew there was a better quote. Somewhere in the Trails library, or perhaps Google books or WorldCat, was a quote about corn. During my many caffeine-induced, bleary-eyed late nights searching hopelessly for something else, my brain had, thankfully, made a mental note about a corn quote.

But where was it? Was it even 1862? So the hunt was on. Once we pulled up the primary source in its entirety, I immediately regretted it. “Too gross,” I said to myself.

Checking with some of my closest peers, though, they noted that the quote had already been used by several notable historians. Surely, if they can talk about bowel movements, so can we.

George Templeton Strong, September 24, 1862 (P 261 of ‘Diary: The Civil War 1860-1865)

We traced the position in which the rebel brigade had stood or bivouacked in line of battle for half a mile by the thickly strewn belt of green corn husks and cobs, and also, sit venia loquendi, by a ribbon of dysenteric stools just behind.

It was the perfect accompaniment to the sign’s text and the Redwood image. It left very little to the reader’s imagination but fell short of other, four-lettered synonyms that would have pushed us towards a “PG-13” rating.

I pitched it to the bosses, content experts, back to John, and even our design team just to be sure it wasn’t too gross. Despite some initial hesitation, the quote earned a resounding “thumbs up.” So we edited the panel, sent it to fabrication, and Trails staff will install it in the next several weeks. You can find the sign on the northbound lane of Buckeystown Pike, Adamstown, MD. (39° 16.798? N, 77° 27.818? W) Go find it next time you are out there. Check in, use a hashtag or two, and enjoy the beautiful countryside.

In fact, every time you find a Trails sign, do me/us a favor. Check in, take a photo, #civilwartrails, and post it on Facebook or Twitter. ‘Vielen Dank’

So why bring this up?

In my travels, I’ve read hundreds of interpretive signs. The writing is often by a historian for historians and is too dense or lofty. Other signs are beautifully designed with artwork fading skillfully behind a poignant, period quote and otherwise lack context, requiring the visitor to already know who, what, when, where, and why.

Yes, folks, I’ve even read Civil War Trails signs that left me confused, re-reading certain sentences or scanning the landscape for additional interpretation. Many signs are not memorable. They don’t equip your mind with the necessary props to imagine the struggles or events that played out before you. This is especially important when the landscape has drastically changed or when it is devoid of any other related features.

This is troubling to me because I am convinced that the average visitor isn’t you, the ECW reader. It’s not Dr. Chris Mackowski or the eminent Robert Lee Hodge. It is more likely to be the hipster couple on a rural byway searching out the local winery or frustrated parents whose clan became unruly during the six-hour trip back from their grandparents. It’s the wife or daughter, held hostage as the “buff“ behind the wheel insisted that the 1864 campaign route was a prettier drive than the bypass that GPS suggested.

In each example, a DOT historical marker, Trails site, or NPS wayside provides a recognizable opportunity to pull over, get your bearings, let the kids run, or stretch your legs.

A historian who I’ve looked up to for many years recently reminded me that our front-line soldiers are these interpretive signs, open 24-7. If the sign isn’t attractive, easy to read, contextual, or memorable, we as a historical community might not have another shot to get someone turned onto the Civil War—or any public history endeavor, for that matter. One bad sign will reaffirm that the Civil War was a sepia-toned, dusty, past-tense history comprised of complex regimental movements, corps numbers, and dead generals—in other words, irrelevant to the visitor.

If we cannot make the ground on which they stand come alive, if the story board doesn’t follow them back into the car in some capacity–be it curiosity, humor, or disgust–then we’ve failed.

Such is the plight of the public historian.

So. Poop. Too tangential? Too gross? Does it add or does it distract? Where are our boundaries and when should we push them?

See you on the Trail.

Good points about attracting potential Civil War fans! And my 11 and 14 year old grandkids would be grossed by the “stools” — and fascinated at the same time! And repeat the quote endlessly!

Sometimes an otherwise “gross” reality carries a connotation that some folks find would just as soon ignore. But, as with so many things in life, there is another side to the story. When archaeologists discovery pre-historic sites dating back thousands of years they often discover human waste – scientifically named “coprolites”. Detailed analysis of the coprolite’s contents reveal much about the health and diet of that culture – findings otherwise difficult to make otherwise.

Of all the Civil War “stuff” I’ve read–and that is a LOT of stuff!–one thing I have never forgotten was one soldier’s comment that Rebel poop was different than Yankee poop. The sure way to differentiate between the two was that Confederate armies ate more corn, and had more semi-digested corn kernels in their poop. “Scat reading” was apparently a thing back then–tracking and such–so this small piece of information was, apparently, helpful. I vote yes on the poop info!

Thanks for the responses Meg, Dale and Bob. My main point here was to test the waters and determine just how far we can push and interpretive experience. I think there is a fine line between effective and fanfare. For instance if G.T. Strong used shit instead of stool would I have used it on a sign? If so, would it have been effective or would we have solicited nasty responses from parents? It comes as no surprise to any of us that 19th century letters are full of language we wouldn’t readily use today but can we successfully utilize them in our interpretive endeavors? I wonder not just about interpretive signage but if the boundaries for exhibit labels could be pushed a bit too. Not a recitation of materials, patents, makers, etc. (connoisseurship) but about who used it, how it was altered, why it was kept, broken, etc. Additionally, I’ve noticed a trend in battlefield tours to now move away from sweeping comments about battalion maneuvers to a reliance on quotes from enlisted men and more of a localized lens into the events.

Words (symbols) are tricky things and often place us upon a slippery slope. In this age when there’s always someone waiting and willing to take offense at the slightest gaff (intended or otherwise) there is a tendency to tread softly. The reality is that truth isn’t always pleasant but that doesn’t make it any less important to face it, does it? I wouldn’t worry much about nasty responses from parents…most children love a good poop joke and parents deluded enough to think otherwise are kidding themselves. I’m one of those who like those personalized quotes from the men and women who were so deeply affected by the war; the little personal insights that bring it to life. I seem to be incapable of actually remembering (for long anyway) the often complicated maneuvering of opposing forces…Ed Bearss I “ain’t”!

No one said history was always pretty!

And aren’t there myriad ways to hide the actual word? %#@* for instance, or s__t? Or simply (stool) within parentheses where an inappropriate word might have been? Personally, I think using “stomachaches” is a hoot–we know what was really going on . . . alas.

In my studies of field hospitals and other places where there were no planned out solutions for sanitation, or simply no legs to get a soldier much of anywhere, I find it is better to be direct. Empathy is often overlooked as a way to relate to soldiers, but everyone has to poop and pee. Depending on others to help in this most personal of experiences was often, initially at least, psychologically devastating to many young men. I am no fan of General Lee, but I feel terrible for him at Gettysburg. Here he was, a Southern icon, and he was hoping no one else “surprised” him either at the privy, or changing his drawers when he didn’t quite make it. ADC Walt Taylor had quite a job to do, and it all makes them so much more human.

Really great thoughts here! Thanks!