“Unparalleled Insult and Wrong to the State”: Unionism and the Camp Jackson Affair of May 1861 (Part 2)

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome guest author Kristen M. Trout

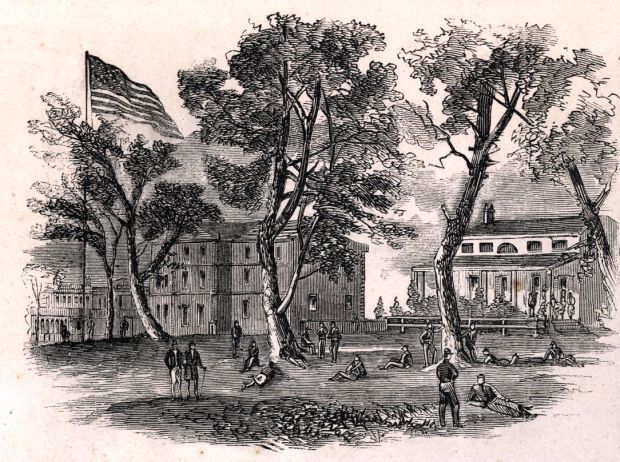

Just south of St. Louis stood the St. Louis Federal Arsenal, filled with over 38,000 rifles and muskets that the secessionists (under the name Missouri Volunteer Militia, which was formed from the Minutemen) aimed to capture just as they did before at the Liberty Arsenal on April 20. Newly-appointed commander Nathaniel Lyon and his Home Guards were ordered by Secretary of War Simon Cameron to seize the weapons and ship them to Illinois. An estimated 21,000 rifles were taken across the river on April 26. On May 1, Jackson ordered a regiment of the Missouri State Militia to conduct military exercises at Lindell’s Grove (site of Camp Jackson), just west of the city. Eight days later, a steamship delivered four smoothbore cannon and 500 muskets from the Confederate Government to aid in Jackson’s efforts.

Weary of the mobilized militia practicing military maneuvers just several miles from the arsenal, Lyon reconnoitered Camp Jackson on May 9 reportedly disguised as a woman and discovered the munition crates.[1] He was right in his suspicions that the secessionists were after the arsenal. Missouri’s governor aimed to attack the stronghold with around 700 troops. On May 10, Lyon led around 8,000 volunteers to Camp Jackson, where he surrounded the militia secessionists under Gen. Daniel Frost, and delivered an ultimatum:

“I do hereby demand, of you an immediate surrender of your command.”[2] In response, Frost wrote, “I never for a moment having conceived the idea that so illegal and unconstitutional a demand […] I am wholly unprepared to defend my command from this unwarranted attack, and shall therefore be forced to comply with your demand.”[3] Approximately 689 officers and men surrendered their weapons and prisoners.[4]

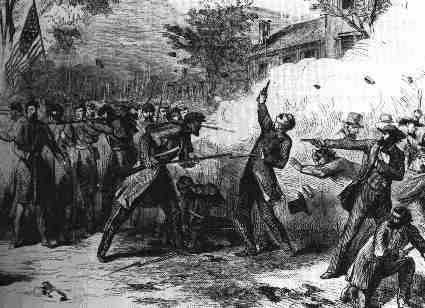

The prisoners were split in two groups to march down Olive Street, a plank road running from the former secessionist camp to the arsenal. On either side of the column of prisoners were Francis P. Blair, Jr.’s and Henry Boernstein’s regiments of home guard. Both Nicholas Schuettner and Franz Sigel’s home guard regiments remained at Camp Jackson to guard the surrendered weapons.[5] While moving along Olive Street, Lyon’s troops, mainly German immigrants, were heckled by a group of protesters. Rocks and dirt, along with anti-German and pro-Confederate slurs, were thrown at the Federal troops. What happened next, however, no one can say.

Historical Society.

One 15-year-old schoolboy from St. Louis High School recalled, “the massacre was started by a boy, a boy of my own age. He was quite near me and I saw his act […] this boy picked up a clod of dirt and pitched it at their officer, Captain Blandowski […] The raw undisciplined recruits were beyond his control. In an instant, the whole line fired a volley into us!”[6] This high schooler would later serve in the Army of Tennessee in an Arkansas infantry regiment, and fight at the battles of Belmont, Corinth, Chattanooga, Missionary Ridge, Resaca, Kennesaw Mountain, and Atlanta. William Sherman and his son Willie were present, recalling a drunken man holding a pistol who fired on the Federal troops, wounding a soldier. “The regiment stopped,” he remembered, “There was a moment of confusion, when the soldiers of that regiment began to fire over our heads in the grove.”[7] Soon though, as historian Louis Gerteis states in his book Civil War St. Louis, “they fired directly into the crowd,” which left 28 people dead. Another regular army and Mexican War veteran, Ulysses Grant, recalled: “the secessionists became quiet, but were filled with suppressed rage.”[8]

State Guard and, later, the Army of Northern Virginia. Courtesy of the

Missouri Historical Society.

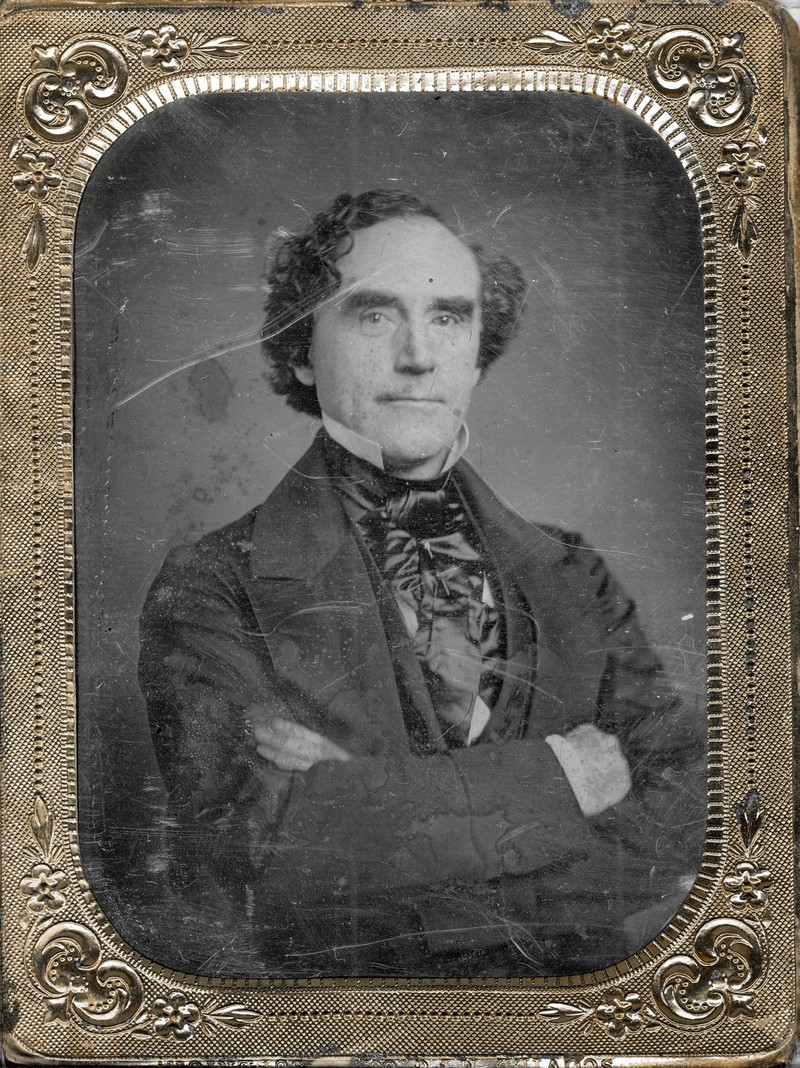

The rage Grant spoke of in his recollections of the Camp Jackson Affair of May 10, 1861 blazed through Missouri like wildfire. The conditional Unionists, like former Missouri Governor Sterling Price; Missouri State Senator and War of 1812 veteran Nathaniel W. Watkins; son of explorer and national icon William Clark, premier architectural engineer, Meriwether Lewis Clark; and West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran Thomas Beverly Randolph, would all take up arms against the United States in the wake of the Camp Jackson Affair and fight to bring Missouri into the Confederacy. These high-ranking officials and former military officers became commanders in the Southern-leaning Missouri State Guard, the Missouri General Assembly-approved military force authorized the day after the Camp Jackson Affair.

The Military Bill, officially titled “An Act to Provide for the Organization, Government, and Support of the Military Forces, State of Missouri,” gave Governor Jackson overwhelming power to create and supply a new force that would defend the state from an invasion by the United States Military and pro-Union militias. General William Harney, commander of the Department of the West for the Army, agreed to allow this new guard under the command of Sterling Price to operate and control Missouri except for St. Louis, where the United States Army would operate. In response to Harney’s neutrality agreement, Lyon and Blair decried his softness and declared war against Jackson’s state government and guard. The fight for Missouri had begun.

* * * * *

Kristen M. Trout is the Programming Coordinator and Historian at the Missouri Civil War Museum in St. Louis, Missouri. She graduated from Gettysburg College in 2014 with a BA in History and Civil War Era Studies, and is currently pursuing her MA in Nonprofit Leadership and Management at Webster University. A native of Kansas City, Kristen has a fond interest in the Civil War in Missouri, Civil War medicine, and the war experiences of soldiers.

[1] Jeffrey S. Prushankin, “They Came to Butcher Our People: The Civil War in the West,” Struggle for a Vast Future: The American Civil War, Aaron Sheehan Dean ed. (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2006), 135.

[2] N. Lyon, Captain, Second Infantry, Comdg. Troops, to General D.M. Frost, Commanding Camp Jackson, 10 May 1861, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (hereafter cited as OR), 1, iii, 6-7.

[3] D.M. Frost, Brig. Gen. Comdg. Camp Jackson, MVM to Capt. N. Lyon, Commanding US Troops, 10 May 1861, OR, 1, iii, 7.

[4] The numbers of troops on both sides of the affair varied based on the source. Historians Adam Arenson and Louis Gerteis agree that there were 8,000 Federal troops under Lyon and Blair; however, they strikingly differ on the number of secessionist troops (Arenson says 1,200, while Gerteis says 600). Most other sources, including the MIssouri History Museum and historian William C. Winter argue that there were between 600 and 700; Louis Gerteis, Civil War St. Louis (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001), 103; Adam Arenson, “How St. Louis Was Won,” The New York Times, 11 May 2011, accessed 6 January 2017, https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/11/how-st-louis-was-won/; William C. Winter, The Civil War in St. Louis: A Guided Tour (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1994), 41-53; “Camp Jackson,” Missouri History Museum, accessed 6 January 2017, http://www.civilwarmo.org/educators/resources/info-sheets/camp-jackson.

[5] Gerteis, Civil War St. Louis, 107-108.

[6] Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes, ed., The Civil War Memoir of Philip Daingerfield Stephenson, DD (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 5

[7] William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General Sherman (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1889), ebook, Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4361/4361-h/4361-h.htm.

[8] Ulysses S. Grant, Memoirs of General US Grant, Complete (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885), ebook, Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4367/4367-h/4367-h.htm.