Malvern Hill: A Victory With The Look And Feel Of Defeat

ECW welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

“I have supped full with horrors. Direness, familiar to my slaughterous thoughts Cannot once start me.” — William Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 5, Line 13-15

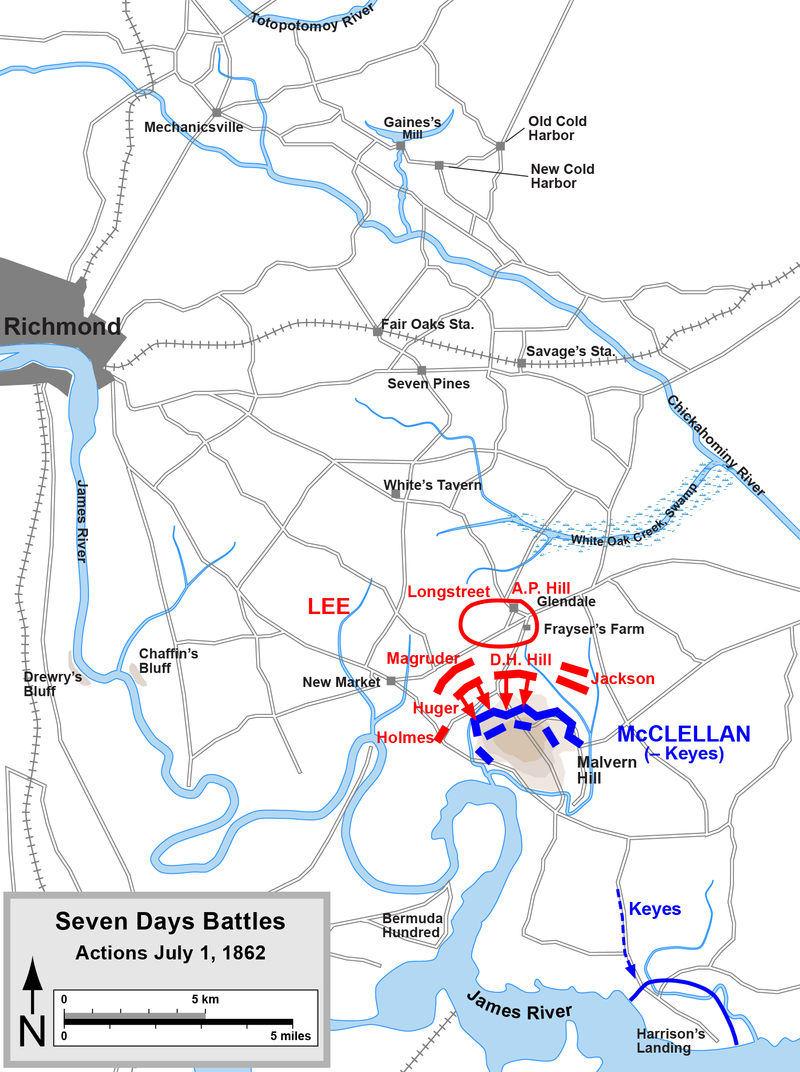

The Army of the Potomac emerged the clear winner at Malvern Hill, the last of the Seven Days Battles fought around the Confederate capital of Richmond. The Southerners suffered 5,650 casualties on that afternoon of July 1, 1862, mostly killed or wounded. The Northern casualty total was 3,007. Surveying a field littered with the bodies of his men after the fighting, Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill declared “it was not war, it was murder.”[i]

The Federals’ victory celebration was short-lived. To the surprise of many of his men, Union commander Major General George McClellan issued a withdrawal order that night. And, with that, the Yankees exited the hill in what one soldier called “a regular stampede.” Wounded comrades were left behind, crying out for help. Union General Darius Couch wondered how soldiers “who had fought so magnificently… were now a mob.” Writing in his journal, First Regiment U.S. Sharp Shooter Sgt. George A. Marden used the French idiom “sauve qui peut”— meaning “general panic”— to describe the battle’s aftermath[ii]

How did this decisive victory emerge with the look and feel of a defeat? A perfect storm of variables— many determined prior to the battle— converged at Malvern Hill that day. Before examining those factors, however, consider a detail of the battle, as reported by Marden and several Sharpshooters on the Union left.

By the afternoon of July 1, Yankee V Corps infantry and nearly 200 pieces of artillery were well-positioned atop Malvern’s slope. They faced down the hill, over a broad expanse of cleared fields, to a tree line a mile away. Other Federal corps and the artillery reserve were stretched around to the southeast of the hill, forming a long right flank. United States Sharpshooter (U.S.S.S.) marksmen, carrying breech-loading rifles, had scattered behind shocks of harvested wheat and in gullies and woods in front of the left and center Union lines.[iii]

Late in the afternoon, after skirmishing and artillery exchanges, the fierce fighting commenced. Marden, a staff aide with the U.S.S.S. command on the left flank, observed enemy infantry charging forth “in solid lines… shrieking like devils.” Down slope, on the Sharps skirmish line, Sgt. William O. McLean spied “rebels pouring out of the woods by thousands.” The skirmishers fired and the big Union guns opened up, lobbing shells “right in their midst.” Skirmisher Brigham Buswell, who also witnessed the barrages, reflected “I had seen slaughter before but nothing to compare with this… I cannot describe it… [the grape shot] would mow a wide path wherever they passed.”[iv]

The Sharpshooters backed up the hill to the Federal lines, rapidly firing their breech-loading rifles to slow their foes. Despite rifle and artillery volleys, McLean wrote, the brave attackers repeatedly charged forward “in such immense numbers that our boys wavered for an instant.” Marden also noticed the Union line faltering and worried the guns might be overrun. “[If so] they would turn our left and the Army of the Potomac would be a thing of history,” he wrote. Two regiments of reinforcements arrived, formed in a hollow, and on the next attack “rose, gave a cheer, a volley and charged the rebel foe, and the day was won,” the soldier reported.

“It was the roughest time I ever had, and I can’t say that I ever want another like it,” concluded McLean, likely reflecting the sentiments of many Union soldiers who fought at Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862. “The roar of the artillery and musketry, the groans of the wounded, the bursting of shells and the excitement… must be seen to be realized.”[v]

It had been a hard fight, but things had ended well for McClellan’s men. How did it digress into the mob scene Darius Couch observed?

By July 1, after a three-month-long campaign, the Federal retreat in the face of victory largely was predetermined. McClellan’s ultra-cautious leadership had been no match for the aggressiveness of his recently-appointed Army of Northern Virginia counterpart, Gen. Robert E. Lee. It took three months for McClellan, who wrongly assumed his army was outnumbered, to carefully creep eighty-five miles up the Peninsula to reach Richmond’s gates. After escaping a month-long federal siege of Yorktown, the Confederates slowed their enemy’s progress by fighting, falling back and fighting again in five subsequent battles. There were tactical Union victories, but nothing substantial to show. The Southerners— under the command of General Joseph E. Johnson until he was wounded in June— had worn down their opponents by the time of Seven Days Battles. When his June 25 offensive probe at Oak Grove near the capital’s defenses met stiff resistance, McClellan was rattled and withdrew. Now under Lee’s command, the Confederates followed and attacked; McClellan retreated again and so on, for the Seven Day’s duration. His caution and paranoia kept growing. Lee’s army had been plagued by poor communications and miscues and won only one of the Seven Days Battles, sustaining a high casualty rate. Yet McClellan abandoned plans to invade Richmond, retreating south. His goal: the James River and the cover of Union gunboats off Harrisons Landing.

A week of fighting by day and retreating by night on extremely short rations— after eleven weeks of the Peninsula Campaign— had weakened and exhausted the Federal ranks. Low morale had become an issue with ever increasing numbers of malingerers and deserters. The order to retreat after victory pushed spirits lower. Marden lamented “the enemy were whipped and yet we were to ‘skedaddle’ once more.” Some officers expressed contempt, Lt. Gen. Philip Kearny declaring his commander “prompted by cowardice or treason.”[vi]

Although discipline in the ranks had held up to now, McClellan’s withdrawal command constituted a breaking point. Certainly not all or even a majority of the Union soldiers stampeded when that command was given, but many did. Wagons, supplies and some artillery pieces were abandoned. Many weapons discarded. Wounded left behind. No soldier wanted to be killed on the last skedaddle of the Seven Days.[vii]

The retreat, afflicted by a driving rain, was horrific. “Men worn out with want of sleep and fatigue slipped in the mud like drunken men,” Marden remembered. “The longer we rode… the worse the road became… Horses and mules lay down in traces and never kicked again.” The soldier and several comrades rescued and carried a wounded U.S.S.S. officer, eventually loading him into an abandoned ambulance and delivering him to Harrisons Landing. “The Lt. Col. got on a boat… Lucky man,” Marden reflected. “I would give a month’s pay to be wounded slightly in the arm.” To conclude, the soldier borrowed from the Shakespeare quote at this article’s beginning, writing: “In short, things are gloomy. I have supped full with horrors for a week and wouldn’t object to a few weeks of rest in N.H. That however is out of the question.”[viii]

Over the next few weeks, the Washington leadership abandoned any hope of McClellan expediting an end to the war by attacking the Confederate capital. The Peninsula Campaign was terminated; the general and his forces shipped home. The South’s rebellion would continue for two years and ten months. The Army of the Potomac would go on to “sup” on horrors of a far grander scale at Antietam, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and other battlefields well north of Richmond.

On July 1 at the Malvern Hill battlefield site, Emerging Civil War Series author Doug Crenshaw will speak at 1 p.m., drawing on material in his new book, Richmond Shall Not be Given Up: The Seven Days’ Battles, June 25-July 1, 1862. Other events at this National Park Service will include military and civilian encampments, living history presentations and battlefield tours. NPS listed the site as “the best preserved Civil War battlefield in central or southern Virginia,” thanks to the collaborative efforts of the Civil War Trust and other preservation organizations. For more information, click here.

Visit the Civil War Trust website for more information and a detailed map of regimental battle positions.

[i] D.H. Hill, “McClellan’s Change of Base and Malvern Hill,” appearing in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 2 (New York: Century Co., 1887) 394; Civil War Trust, “10 Facts: Malvern Hill” https://www.civilwar.org/learn/articles/10-facts-malvern-hill, accessed May 25, 2017.

[ii] Letters of Richard Tylden Auchmuty, Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac, July 5, 1862 (Privately published, 189?); Darius Couch, Civil War Record RG 94 (M-1098:5), quoted in Stephen Sears, To the Gates of Richmond (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992), 338; George A. Marden, Journal entry of July 8, courtesy of Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College, Hanover N.H.

[iii] Marden Journal, July 8; Capt. C.A. Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters In The Army Of The Potomac (St. Paul, Minn.; The Price McGill Company, 1892), 143-146 ; Brian K. Burton Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles. (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2010) 308; Civil War Trust, https://www.civilwar.org/learn/civil-war/battles/malvern-hill, accessed June 1, 2017.

[iv] Marden Journal, July 8; William O. McLean, letter to family, July 5, , Cherry Valley Gazette, Cherry Valley, N.Y., July 23, 1862; Brigham Buswell, memoir excerpted in Civil War Times, April, 1996.

[v] Marden Journal, July 8; McClean letter to family, July 5.

[vi] Marden Journal, July 8; E.M. Woodward, History of the Third Pennsylvania Reserve (Trenton, NJ: MacCrellish & Quigley, 1883), 124-125, quoted in Sears, 338.

[vii] Sears, 337-338

[viii] Marden Journal, July 8

Um, not A. P. Hill: D. H. Hill.

You are right Craig. Sloppy editing of my own writing. I got it right in the footnote at least. Thanks for pointing this out.

A nice analysis. Three points: (1) As your post suggests, Malvern Hill was a more interesting (and at one point competitive) battle than is generally accepted. One hopes that Frank O’Reilly will complete his project and publish a study of this misunderstood fight; (2) IMHO McClellan lost this campaign in April-May when, with significant numerical superiority, he moved ponderously up the Peninsula facing the ever-ready-to-retreat Joe Johnston, all while being buffaloed by the weather and his fictional estimates of opposing numbers – by late June the ANV (according to Leon Tenney) likely had a strength which was at least equivalent to McClellan’s and his base at White House Landing was clearly threatened by the addition of Jackson’s force to the ANV; (3) after retreating to Harrison’s, McClellan did have communication with Washington in late July about possibly mounting an offensive on the other side of the James but in vintage McClellan style it was couched in new demands for significant reinforcements, etc. The “plan” only seems to have emerged c. July 21 and was not (as McClellan would have had us believe) behind his decision to retreat to Harrison’s.

Thanks John. You make excellent points that fill out my brief overview of the Peninsula Campaign. To add to your point about reinforcements (which I wish I’d made originally), just-appointed general-in-chief George Halleck offered McClellan 20,000 men late in July, to restart the Peninsula Campaign. Convinced that Confederate “reinforcements are pouring into Richmond,” McClellan insisted he needed 55,000. As Stephen Sears points out in “To The Gates of Richmond,” that pushed Halleck to declare that the Army of Potomac commander “should never plan a campaign.” By early August he’d ordered his general and his army north.

Rob: As you know, there is nothing more annoying/frustrating/aggravating than reading McClellan’s voluminous contemporary correspondence. While I think that Sears may occasionally overreact when McClellan;s name is mentioned, I sympathize. If I had edited those papers I’d be even more cynical about him than I am. Nothing is ever stated decisively or unequivocally. Everything has qualifications, conditions, footnotes, and a tone of “cya”. I cannot imagine dealing with this guy in the positions of Halleck, Stanton, or Lincoln without losing all patience. The July back and forth about taking the offensive from Harrison’s fit the m.o. perfectly and by that point was eminently predictable.

Righto! I actually have not read that much of his correspondence, but from the primary and secondary sources I have read I can say this: Good thing for the Union that Lincoln defeated McClellan in the 1864 election!

John I’m a huge fan of 7 days and specifically Malvern Hill, is Frank ‘O Reilly of Fredericksburg fame writing on Malvern Hill? Any information would be much appreciated…HAPPY 4TH

The balance of forces during the Peninsula is much closer than usually believed, and it tainted by different measurements of strength. In Johnston’s and Lee’s army the reported “PFD” was the musket strength, after all deductions for non-combatants with the trains, hospitals, regimental cooks, officers servants etc., whereas the Army of the Potomac reported these men as all men paid and doing duty, including the extra duty with the trains etc. To convert Federal PFD into rebel PFD you need to deduct 1/5th-1/6th of the PFD, and sometimes the officers.

At Yorktown there were about 23,000 rebel effectives on 5th April (Magruder having received the brigades of Wilcox, Pryor, Colston and a few other units) and ca. 29-30,000 on the 6th (with the arrival of Early’s division). McClellan’s force had ca. 46-48,000 effectives as the rebels calculated it.

Over the next weeks the rebels added forces and McClellan added Casey, Hooker and Richardson around the 16th, as they were delayed by the storm of 6th-11th April. By 23rd April the balance is ca. 64,000 rebels vs 64,000 Federals (in effectives as the rebels counted it), with McClellan gaining another 8,000 on the 24th as Franklin’s division arrives.

By 21st May Johnston has been reinforced by another two divisions, Huger’s from Norfolk and AP Hill (formed at Richmond from brigades recalled from Fredericksburg, NC and SC) to give him ca. 81,000 effectives vs McClellan’s 72,000.

It evens up again after Seven Pines, with McClellan getting 12 regiments that replaced his losses (72,000 effectives), then McCall’s division of ca. 8,000 to give 80,000 effectives. Lee meanwhile gains 2 brigades to AP Hill (Archer’s from Fredericksburg and Pender’s from NC), 4 from NC (Walker, Ransom, Daniel and Wise), 1 from Georgia (Lawton’s) and then the 6 under Jackson. In terms of combat effectives as the rebels figured it he had a bit more than 100,000 excluding the Richmond defenses.