Dranesville: A Troubled Town, Part 5

Part 5 in a series.

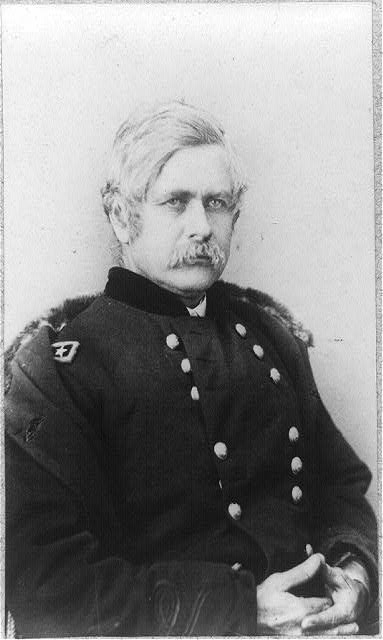

It was Brig. Gen. Edward Ord’s turn. In the past three weeks, a brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves had marched out of Camp Pierpont towards Dranesville, gathered wagonloads of supplies, and marched back. On Dec. 3, it was Brig. Gen. John F. Reynolds’s 1st Brigade; on Dec 6, George Meade’s 2nd Brigade went out. And in the afternoon of Dec. 19, Ord got his orders. Tomorrow morning, Dec. 20, he was to take his infantry, accompanied by cavalry and artillery, out to Dranesville to fill his wagons.

As a primary assignment, though, Ord was to keep an eye out for any Confederate pickets and drive them back, as reports had come in that local Unionists were again being “carried off.” Ord forwarded the instructions to his regimental commanders; his brigade would leave camp at 6 a.m. the next day.[1]

The following morning, Ord’s men left camp. The brigade had four regiments of infantry, and Ord’s superior, Brig. Gen. George McCall, had also given him the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles (the Bucktails) as extra support. Joining the column was Capt. Hezekiah Easton’s battery of four cannon and the 1st Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry. With the infantry, artillery, and cavalry, Ord could count on some 4,000 men. Trailing behind Ord came John Reynolds’s brigade, which stopped at a stream called Difficult Run. After the ambush the previous month and reports of pickets in the area, McCall undertook every one of his movements with overwhelming force. To aid in gathering supplies, Ord took a long train of wagons with him.

While Ord’s column headed out from Camp Pierpont, the Confederates were preparing an expedition of their own. Most of the Confederate army, at the time called the Army of the Potomac, was huddled around Centreville just outside of Manassas. The Confederates needed more food and hay before they headed into the doldrums of winter and Dranesville, which lay about sixteen miles from Centreville, offered a perfect location to get the resources from.

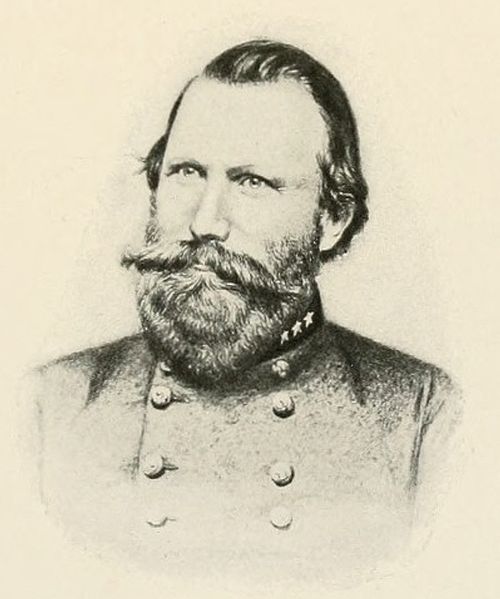

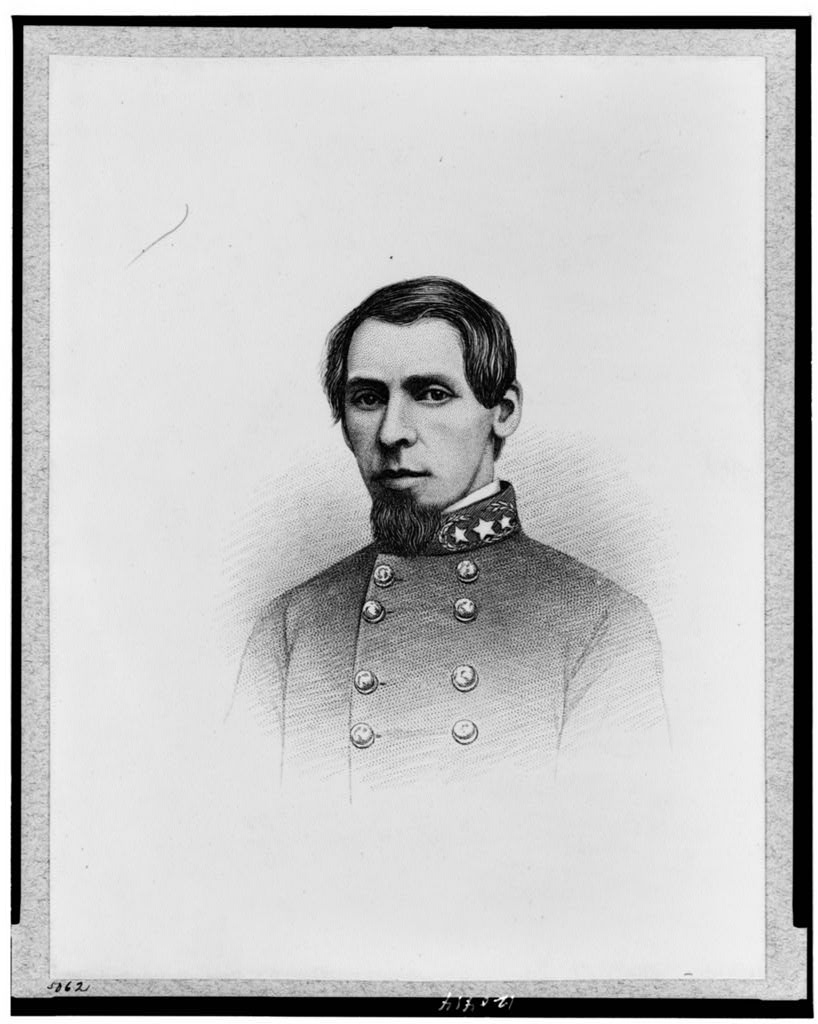

A veritable hodgepodge of soldiers were put together into an ad-hoc brigade. There were four regiments of Virginian, South Carolinian, Alabaman, and Kentuckian infantry, about 150 cavalry troopers from the Old Dominion and North Carolina, and a four-gun battery from Georgia. To command these 1,600 or so men, the Confederate high command turned to Brig. Gen J.E.B. Stuart.

Stuart was 29 years old in December, and had made a name for himself both at Manassas in July, and in the intervening fall months with his brigade of cavalry. Stuart’s expedition to Dranesville would be his first time commanding any sizeable force of infantry. He had eagerly wanted combat, writing to his wife, “Why don’t he come?” [emphasis in original.] Now was his chance to fight.[2]

The Confederate infantry marched to Stuart’s headquarters early in the morning of the 20th. They met their commander there, as well as all the wagons the Confederacy could send to gather supplies. Even to get to the staging area proved exhausting to some, and Second Lieutenant John Bratton from the 6th South Carolina wrote that his “boots were already telling on my feet, and I threatened to turn back from that point.” Bratton continued, though, because, “My mind was possed [sic] with the idea that trouble was ahead and I kept on.”[3] Stuart’s column set off towards Dranesville.

Meanwhile, Ord’s brigade had dropped off their wagons and foragers at the home of John Gunnell.[4] Gunnell had been stamped as “a squire and noted secessionist” and the Federals used his farmland to draw their supplies from.[5] The Federal soldiers were already familiar with the area—every time they went on their expeditions, they went to Gunnell’s home, and two of Gunnell’s nephews had been arrested in conjunction with rounding up prisoners associated with the ambush at Lowe’s Island.

Though Ord’s original instructions were to gather supplies and keep an eye out for any Confederate forces, the old army officer took it a step further. He ordered the men not detailed to forage to continue down towards Dranesville, and he later wrote to his superior, Gen. McCall, “satisfied that, though I might be exceeding the letter of my instructions, should I find the enemy and pick up a few you would not object.”[6] And so Ord’s men advanced to Dranesville, headed straight for Stuart’s column.

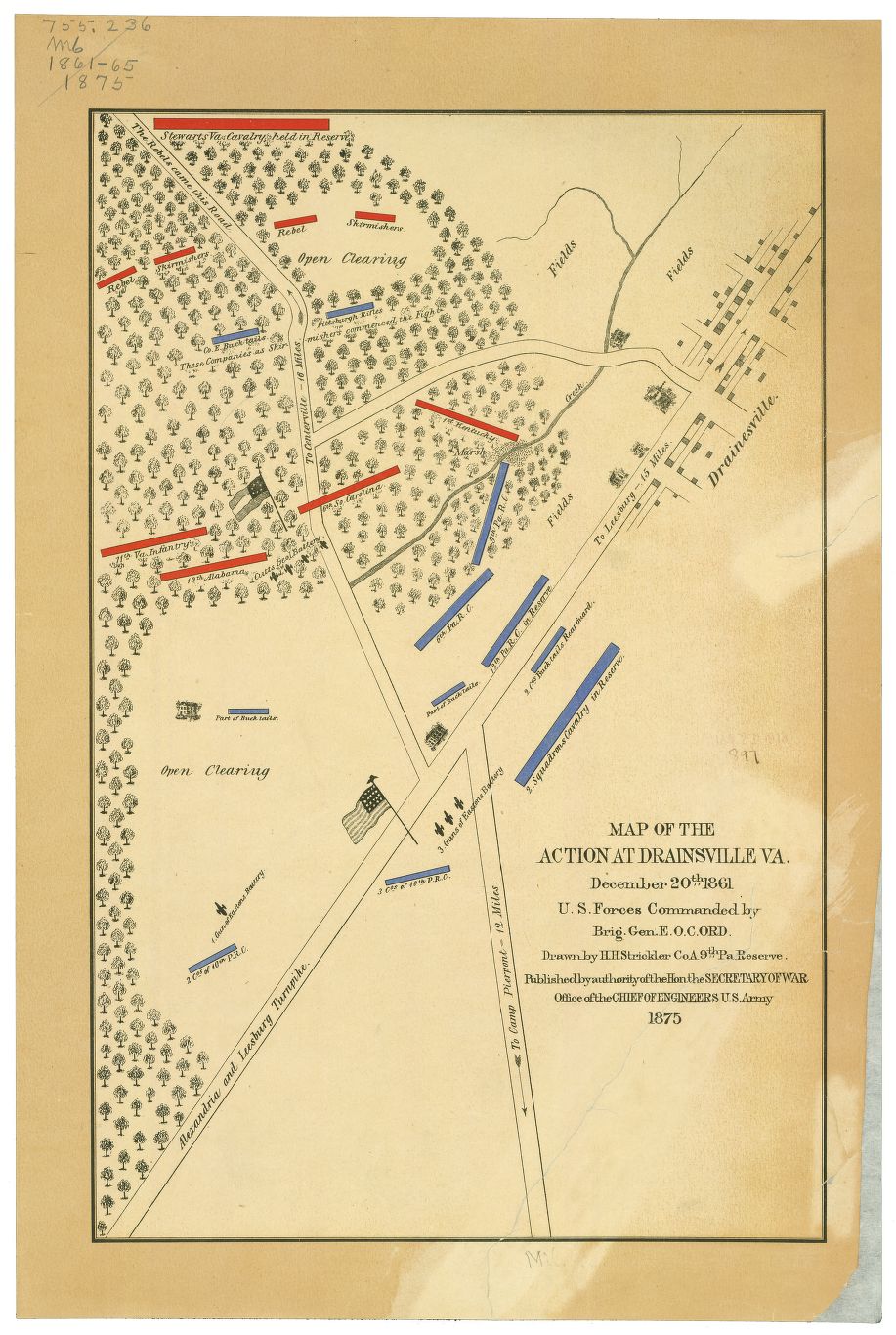

As the Federal soldiers neared the town, Ord deployed his skirmishers. Two companies of Pennsylvanians headed south down the Centreville Road, advancing through heavy undergrowth that made visibility and movement both difficult. It was the middle of the afternoon, Friday, December 20.

One of the Pennsylvanian riflemen, Pvt. George Dean, remembered that in a lull of the march he was “trading off a piece of corned beef for some salt pork,” when the still day was broken by the first scattered shots of a battle. The two companies of Federal skirmishers quickly gave ground as the vanguard of Stuart’s regiments shook themselves into a battle line and began to march against them.[7]

Stuart’s advance was hampered by the dense forestry, but Ord’s main column, having the wide surface of the Leesburg Pike, had no such problems. Thus Ord’s men were able to sprint into battle, and the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles even took up defensive positions inside the large brick Thornton House. Knocking windows out, the Riflemen had a ready-made fortress.

While Ord finished bringing his infantry to bear, Stuart continued to struggle. On his right, part of the 11th Virginia got hopelessly lost in the thick vegetation and never got into the fight. Meanwhile on his left, the 1st Kentucky and the 6th South Carolina advanced on each other and opened fire, leading to self-inflicted casualties. All the while the Federal infantry began to send ripples of rifle fire down the Centreville Road. To counteract the Federals, Stuart tried to bring Capt. A.S. Cutts’s guns from the Sumter Light Artillery. In the confines of the road and hemmed in by the woods, Stuart could only unlimber two guns at a time. Nonetheless, Cutts’s cannon were soon firing. A Bucktail remembered that the projectiles “passed over our heads saying ‘Secesh’ and struck in a field just beyond and burst.”[8]

But Stuart, the dragoon officer, would soon be outmatched. Watching the Confederates deploy, Ord brought his own artillery up. Ord had been an artillery officer in the pre-war army, and that expertise soon showed. Besides a hiccup when a cannon was overturned (and quickly corrected), the Federal artillery would rule the day at Dranesville. Under Ord’s careful eye and management, the Union guns began to drop shot and shell amongst the Confederates.

The ensuing destruction left men—most of them seeing combat for the first time—shocked and horrified. Two of the Georgian artillerists were beheaded by a solid shot, leaving their bloodied corpses in the middle of the road. Another Federal shell hit a caisson, exploding the ammunition chests in a grand firework display. Along the infantry lines, the Confederates were struck by the volleys of Union soldiers ahead of them. The 10th Alabama’s colonel went down with a shattered arm and their second-in-command was killed instantly. In the middle of it all sat Stuart, who had wanted a fight so badly. “I was never in greater personal danger,” he proudly wrote to his wife. “Men & horses fell around me like ten-pins, but thanks to God to whom I looked for protection, neither myself nor my horse was touched.”[9]

Edward Ord’s battle line continued to fire into the Confederates. The Federal artillery held up Stuart’s advance, limiting their ability to fire back. One Confederate wrote, “Our Regt did’nt [sic] do much firing from the fact that we were in about two hundred yards of their battery and they could have slaughtered every one of us with canister if we had shown ourselves.”[10] To escape the hailstorm, John Bratton remembered, “The order was given to fall to the ground,” and some of the Confederates dove for protection.[11]

It had been almost two hours since the two forces came into contact. The gunners manning Stuart’s artillery were being torn to pieces, and his infantry was stuck in the thick vegetation under sharp musketry. At the beginning of the action, Stuart took measures to make sure his wagon train could get away, and when he got word it had, he next looked to extracting his soldiers from their situation.

With Col. Samuel Garland’s 11th Virginia Infantry covering the withdrawal, Stuart started to move his men out. In the midst of the retreat, Stuart lost sight of the bigger picture, personally dragging off harness from the artillery and draping them over his saddle. As Emory Thomas, one of Stuart’s biographers, writes, Stuart “lost contact with his infantry and watched his artillery absorb significant punishment, and he responded by collecting harnesses—literally picking up the pieces of a shattered day.”[12]

As the Confederates fell back, Edward Ord had his own problems. He later confided in George Meade that he tried numerous times to get his infantry to counter-attack, but they failed to move. Ord believed “if they had charged when he first ordered them, he would have captured the whole battery and lots of prisoners.”[13] As it was, Ord soon realized he wouldn’t be able to pursue and fell back to Camp Pierpont.

The two-hour battle left about 200 Confederate casualties and about 70 Federal. After the battles at Manassas and Ball’s Bluff neither side was still ready for the casualty counts, and the Federal forces especially did a poor job at removing their wounded, leaving George McCall to complain of the lack of ambulances.[14] Stuart brought his wounded to the Frying Pan Meeting House where they were tended to by locals and soldiers alike. He returned the following day, Dec. 21, to remove his dead. “It was sickening sight,” a Confederate wrote, “To see them piled in wagons like slaughter[ed] pork.”[15]

The Federal army was exultant with their victory. Though it did not replace the losses at Manassas or Ball’s Bluff, it let the blue-clad soldiers know they could win. Congratulatory letters poured in, and Pennsylvania’s governor, Andrew Curtin, ordered that the veterans have their battle flags inscribed with “Dranesville.”

When it comes to accounts of the battle of Dranesville—what few there are—the story of the battle is usually relegated to a meeting engagement of two forces gathering forage. While that is certainly true, it also diminishes the larger narrative of the constant ebb and flow of events around the town in 1861, as this series has tried to depict.

______________________________________________________________

[1] The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion ,Series 1, Volume 5, 480 (hereafter OR, followed by Series, volume, and page number).

[2] J.E.B. Stuart, Letters of General J.E.B. Stuart to His Wife 1861, edited by Bingham Duncan (Emory University: Atlanta, 1943), 19.

[3] John Bratton, Letters of John Bratton to his Wife, edited by Elizabeth Porcher (Privately published, 1942), 50.

[4] OR, Series 1, Vol. 5, 478.

[5] OR, Series 2, Vol. 2, 1287.

[6] OR, Series 1, Vol. 5, 478.

[7] George W. Dean, Dean, “The Battle of Dranesville, Va., Dec. 20, 1861. My First Engagement,” 2, in William Blake Dean and Family Papers, Minnesota Historical Society.

[8] Angelo Crapsey quoted in Pathway to Hell: A Tragedy of the American Civil War, Dennis W. Brandt (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 65.

[9] J.E.B. Stuart Letter, December 23, 1861, Stuart Papers, Virginia Historical Society (VHS).

[10]Philip Franklin Letter, Jan. 3, 1862, Letters of Philip H. Franklin, VHS.

[11] Bratton, 51.

[12] Emory Thomas, Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (Harper & Row: New York, 1986), 100.

[13] George Meade, The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade: Vol. 1, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 238.

[14] OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 5, 476.

[15] Thomas Spencer Letter December 23, 1861, Thomas J. Spencer Papers, VHS.

Interesting account; thanks for posting.