The Naval Civil War in Theaters Near and Far

Civil War military history occurs in the context of “theaters” including the Eastern, the Western, and the Trans-Mississippi with sub-theaters within each. This framework organizes operations in terms of discrete location, environment, interacting events, influences, and consequences.

The naval side of the war consisted of distinct theaters also and these warrant independent definition and consideration. They can be defined as: The Offshore Blockade, Peripheral Coasts and Harbors, Heartland Rivers, and the Wide Oceans.

Carl von Clausewitz defined a theater as: “A sector of the total war area which has protected boundaries and so a certain degree of independence.” Protected boundaries might consist of fortifications, natural barriers, or simply distance. A theater is, “a subordinate entity in itself—depending on the extent to which changes occurring elsewhere in the war area affect it not directly but only indirectly.”[i]

Land and water are disparate mediums for war; their organizations, strategies, tactics, technologies, leadership, and personnel are unique. The wet operational areas are bounded primarily by the interface between land and water and sometimes by immense distances. Some of these zones overlap terrestrial counterparts while others extend far beyond familiar battlefields to the far side of the world.

When land and water theaters overlap, they must operate within a common strategic framework and with some ability for coordination and support. Civil War naval theaters also differ among themselves, largely due to varying degrees of interaction with land operations. Both similarities and differences are instructive.

Almost nothing in the history and traditions of the United States Navy prepared it for the challenges of civil war; peacetime establishments would not shift smoothly into crisis mode. In 1860, the navy was still cruising in small, semi-permanent squadrons on far-flung stations to show the flag and to protect the burgeoning, global American shipping and whaling industries.

It trained primarily to refight the War of 1812—glorious single-ship duels against a foreign foe and commerce warfare with pirate suppression as needed. Massive operations such as blockade, reduction of shore fortifications and heavily defended ports, shallow-water coastal and riverine warfare, combined army-navy operations, and countering elusive commerce raiders were not imagined.

The navy had come a long way since its baptism of fire during the undeclared war with France in 1798. A more efficient organizational structure replaced ad hoc administration of the past. A small but formidable officer corps served with a proud heritage, high esprit, and expert seamanship, which would contribute a core of talent for both sides in the coming conflict.

Officer education had been formalized and modernized at the new Naval Academy in Annapolis.

A body of trained sailors manned the fleet; flogging had been outlawed and alcohol would be banned afloat (for the U.S. Navy) in 1862. Over the first half of the century, the service demonstrated technical innovation and excellence in warship production; it was advancing rapidly in steam and propeller propulsion, and it was leading the ordnance revolution of the era.

However, strategic and tactical vision were lacking. Rapid technological and social change discomforted conservative officers, while glacial promotions discontented juniors. Revolutions abroad in ironclad vessels had been largely ignored. And as events would prove, manpower, material, and infrastructure were totally inadequate to emergent requirements.

That both sides faced the contest with singular lack of foresight or preparation seems incredulous in hindsight; such naiveté appears to be an American characteristic. But the antebellum navy was a small, closely-knit brotherhood in a most esoteric profession. Most of its officers—shipmates at sea—did not wish to think very deeply about fighting each other over distant domestic differences. They could not possibly envision what did happen or the immense effort required.

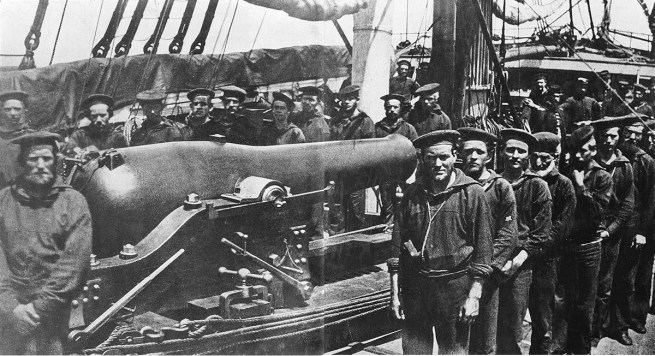

In marked contrast to soldiers, most deep-water sailors on both sides were products of poor, working classes from Northern and European cities rather than small towns and farms. Admiral David Dixon Porter referred to, “As fine a body of Germans, Huns, Norsemen, Gauls, Chinese, and other outside barbarians as one could wish to see, softened down by time and civilization….”[ii]

Historians estimate that 24,000 (16%) of the Union navy was African-American freedmen and escaped slaves; African-Americans also served on Confederate commerce raiders. They were fully integrated into ships’ crews, assigned duties commensurate with skills and experience, and paid identical wages.

Mariners of the era were inclined to be hard, pragmatic, cynical, and profane men who drank too much, fought too much, and prayed too little. Aggressively masculine, they did not aspire to gentlemanly virtues, sacrificial aspirations, or ideological motivations. Aside from the few actual battles, their war was marked by personal struggles with boredom, officers, religion, and alcohol.

Men who manned the brown-water navies on rivers and inland waterways, however, were more likely to resemble Army counterparts. Crews often were recruited from army units and inland states, and rivermen were generally a breed apart from ocean sailors.

The maritime blockade and efforts to avoid it constituted a discrete zone of operations with difficult challenges. It was a bold and controversial strategy, and the most extensive blockade ever attempted, extending over 3,500 miles of Atlantic and Gulf coastline from the surf out to several miles offshore.

The U.S. Navy had never done much blockading but inherited a robust tradition from the British. Navy Secretary Welles undertook an immense procurement and building program adding almost anything that could float from armed ferries and merchant vessels to the most advanced warships, surging the fleet from a third-rate force to one of the largest and most powerful in the world.

Steam propulsion enabled blockaders to keep station more consistently and gave runners a new class of sleek, fast vessels.

A primary purpose of the Confederate ironclad program—starting with the CSS Virginia (ex USS Merrimac)—was to break the blockade, while the Union Monitor class was developed to counter them. The blockade progressively throttled the Southern economy and significantly degraded home-front morale.

The maritime peripheral theater extended inland from those same coastlines to encompass estuaries, bays, deltas, and major and minor ports. Operations were primarily an extension of the blockade and conducted by the same naval forces, but had additional important objectives new to the navy.

Requirements to refuel and maintain steam blockaders necessitated occupation of secure Southern harbors. Political and strategic considerations expanded this concept to include capture of coastal enclaves and cities. Steam and modern armaments enabled reduction or bypassing of powerful shore fortifications that sailing warships could never take on. New classes of shallow-draft vessels were developed, while most ironclads on both sides operated in this theater. Other new technologies contributed in the form of torpedoes and submersibles.

The two services that thought of themselves as entirely independent entities began to glimpse the potential of cooperative operations. But coordination depended more on the personalities of commanders than on conscious strategy or formal organization; in hindsight, strategic opportunities were missed.

Offense and defense on the periphery were relatively well matched. Port Royal, Hampton Roads, New Orleans, and Mobile Bay fell to the U.S. Navy; Galveston was captured by the Union Navy and retaken by the Confederate Navy; the North Carolina Sounds and Wilmington were conquered by combined U.S. Army/Navy operations; Charleston and Savannah held out to be finally seized from the rear by the U.S. Army.

The war on heartland rivers—the Tennessee, Cumberland, Mississippi, James, Arkansas, and Red—was also an extension of blockade strategy, an outgrowth of the Anaconda Plan. In tactics and technology, however, it was an entirely new concept.

History offers few examples other than the Civil War and Vietnam of extensive operations on inland shallow waters involving specialized classes of war vessels manned by naval personnel. Rivers had always been barriers or highways to land forces, but boats employed by armies were little more than transportation platforms for troops and cargo.

After conquering New Orleans, Admiral David Farragut brought his deep-water squadron up the Mississippi as far as Vicksburg, but didn’t stay long and was not comfortable there. Navy Captain Andrew Foote along with civil engineers James Eads and Charles Ellet produced squadrons of innovative steam gunboats and rams for the Union, many adapted from river steamers and some with iron cladding.

U.S. Grant developed excellent partnerships with Foote and Admiral David D. Porter. The navy was a critical element in the Western war from Forts Henry and Donelson, through Shiloh, and up and down the Mississippi to victory at Vicksburg—reducing fortifications, besieging cities, ferrying troops, protecting friendly commerce while suppressing enemy trade, fighting guerrillas. The only fleet action of the war was a Union victory at Memphis.

Confederates tried valiantly to counter with river ironclads and gunboats. The ironclad CSS Arkansas made a spectacular, guns-blazing run through the Union fleet above Vicksburg. On the rivers, land and water warfare meshed most effectively for the Union.

The wide oceans, however, were successful hunting grounds for Confederate commerce raiders operating primarily in the Atlantic and Caribbean. The CSS Alabama got as far as the South China Sea while the CSS Shenandoah encircled the globe. Union Navy Secretary Welles focused resources on the blockade, reluctantly dispatching a few warships to chase Rebels down—usually too little, too late.

This was a familiar form of naval warfare over centuries of European conflict at sea; Americans warred vigorously upon enemy trade in every contest leading up to 1861. Not unlike the strategy of William T. Sherman, commerce raiding targeted the enemy’s economy, home-front morale, and will to fight. Confederates developed a new class of warship: Small, swift, lightly armed cruisers combining the advantages of fast sail with steam and dedicated to destruction of enemy ocean trade.

Eight Rebel raiders captured over 240 Union merchant ships and drove another thousand into foreign ownership.

Maritime insurance rates soared; owners held their vessels in port, and foreign contracts dried up. Powerful shipping and whaling interests pressured the Lincoln administration for peace even with Southern independence. Considering results versus costs, this was the Confederacy’s most effective military campaign.

The Civil War was principally a land conflict but it was not only that; naval operations were more than just peripheral or supporting. Navy theaters of operations complete the picture, providing fascinating and enlightening perspectives on the conflict.

[i] Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Princeton, NJ, 1976), vol. 1, 280.

[ii] James E. Valle, Rocks & Shoals: Naval Discipline in the Age of Fighting Sail (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1980), 19.

Very tight delivery of new information for me. I can only hope that detailed theater info will follow.

Thank you. I plan to expand on each theater in future posts. A presentation on this theme also will be available. Please see CivilWarNavyHistory.com.