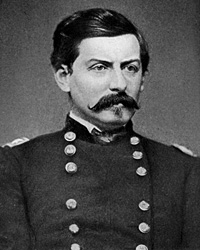

George McClellan in 1861: A Glimpse of Foibles to Come (part one)

ECW is pleased to welcome back guest author Jon-Erik Gilot.

ECW is pleased to welcome back guest author Jon-Erik Gilot.

(part one of two)

More than his battlefield prowess or organizational abilities, George McClellan is remembered for his less-than-desirable traits—quarreling with subordinates and superiors; micromanaging affairs; uncertain decision making; hesitant movement in the face of and wildly overestimating the size of the Confederate armies facing him.

As I’d mentioned in my last article, McClellan’s 1861 campaign in western Virginia can be used as a benchmark against which can be measured his later successes and failures. The campaign was a military and political success during an otherwise dismal summer for the Union, and was accomplished with minimal bloodshed. However, it is also where McClellan first exhibited his most McClellan-esque tendencies of the Civil War.

Let’s examine some of these traits that would rear their ugly heads later in the war.

Quarreling with Subordinates & Superiors:

George McClellan was sure that no one above or below him could win the Civil War—only George McClellan was up to the task. In Western Virginia, he had no shortage of squabbles with his brigade and regimental officers. In a July 3 letter to his wife, McClellan singled out each brigadier, stating “I have not a Brig Genl worth his salt – Morris is a timid old woman – Rosecranz is a silly fussy goose – Schleich knows nothing…”[i]

Rosecrans had been on the receiving end of McClellan’s fury on July 1 after occupying Buckhannon, Virginia, because McClellan feared that Rosecrans had tipped his hand to the Confederates in the area. In a July 2 letter to Mary Ellen, McClellan bragged that Rosecrans was “very meek now after a very severe rapping I gave him a few days since.”[ii] Stephen Sears would relate the rebuke as “so sharp that Rosecrans had appealed to him to delete it from the record.”[iii]

McClellan was equally harsh with Brigadier General Thomas A. Morris, who McClellan would task with holding in place the Confederate army under General Robert S. Garnett at Laurel Hill. McClellan’s gross overestimate of Confederates at Laurel Hill caused Morris to seek reinforcements, believing he was severely outnumbered and vulnerable if attacked. This request infuriated McClellan, who responded with scathing instructions, reading, in part, “I propose taking the really difficult and dangerous part of this work on my own hands. I will not ask you to do anything that I would not be willing to do myself. Do not ask for further re-enforcements. If you do, I shall take it as a request to be relieved from your command and to return to Indiana.”[iv] Following the war General Jacob D. Cox would recall that Morris was in the right—that had the Confederate troops numbered 10,000 as McClellan had believed, he had left Morris vulnerable with only 4,000 to oppose them. Should Morris have been defeated, Garnett’s army would have had a clear path to the vital rail and road junction at Clarksburg.

The rebuke of Newton Schleich was McClellan’s least offensive. Schleich was a savvy Democrat from Ohio who owed his commission more to political stature than military prowess. Schleich would come very near to upsetting McClellan’s plans when, on July 5, 1861, scoffing at McClellan’s slow movement, he ordered an unauthorized expedition from Buckhannon to Middle Fork Bridge, nearer the Confederate troops at Rich Mountain. A sharp skirmish ensued at the bridge, sending the Federal party stumbling back and alerting the Confederates to a possible movement against that sector. McClellan was furious, relieving Schleich of command and reassigning his regiments to Brigadier General Robert L. McCook. Schleich would again prove later in the war that he truly “knew nothing.”

As late as July 19—hours before being called to D.C.—McClellan was still bemoaning the officers under his command. “In heaven’s name, give me some General Officers who understand their profession,” he pleaded to Washington. [v] While early war officers were certainly a mixed bag, McClellan did have capable officers under his command who would distinguish themselves later in the war, most notably William Starke Rosecrans, who would rise to the rank of major general and masterfully strategize the often-overlooked Tullahoma Campaign in the summer of 1863.

McClellan likewise had no issue in quarreling above his rank in the summer of 1861. He would meddle in affairs outside his department in Kentucky and Maryland and scoffed at Winfield Scott—his only ranking officer—and Scott’s proposed “Anaconda Plan.” When called to D.C. in July, McClellan would ignore the chain of command, bypassing Scott entirely in favor of Lincoln and his cabinet.

McClellan’s squabbles with his superiors—namely Abraham Lincoln—and several of his subordinates would continue through 1861 and 1862. These feuds and distrust would often result in McClellan’s . . .

Micromanagement:

George McClellan was a masterful micromanager, seemingly taking satisfaction in overseeing tasks that should have been delegated to subordinates. He would write to Mary Ellen only days after arriving in western Virginia that “everything here needs the hand of the master,” and that “unless where I am in person everything seems to go wrong. He would similarly bemoan to Washington that “I give orders & find some who cannot execute them unless I stand by them. Unless I command every picket & lead every column I cannot be sure of success.” His belief that the army could not move without him would spill over into a belief that the army could likewise not fight without him, remarking to Mary Ellen that “I don’t feel sure that the men will fight very well under anyone but myself,” never mind that troops under Rosecrans and Morris had fought ably at Rich Mountain and Corrick’s Ford, and in the Kanawha Valley under Brigadier General Jacob D. Cox.[vi]

McClellan would be routinely delayed after crossing the Ohio River in the micromanaging of transportation, supply wagons and logistics—traits that would likewise haunt him in the planning and execution of the 1862 campaign on the Virginia peninsula. This style of leadership would regularly lead to McClellan’s . . .

. . . slow movement, which we’ll talk about in part two.

To be continued….

————

[i] Sears, Stephen W., The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860 – 1865, (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1989), 44

[ii] Sears, Papers…, 41

[iii] Sears, Stephen W., George B. McClellan – The Young Napoleon, (New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields, 1988), pg. 86

[iv] Scott, Robert N., The War of the Rebellion, a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume II, (Washington, DC: Gov’t Printing Office, 1882), 208-209

[v] Sears, Papers…, 61

[vi] Sears, Papers…, 34, 40, 61

I am curious what your take would be on McClellan’s political affiliation affecting his perception of the enemy and his reluctance to fight. It seems to me that McClellan showed his true colors in opposing Lincoln for the presidential election of 1864. It is my opinion that his politics dictated strategy in his mind. Having loyalty to the union yet personal fidelity to Southern Democrats seemed to shade his actions.

Hi James,

I wouldn’t read too much into McClellan’s political affiliation, at least not in this early part of the war that we’re discussing here. He had been a Whig until the run-up to the war, when he cast his first ever ballot for Stephen Douglas, and he certainly wasn’t afraid to cross the Democrats during the first campaign. Newton Schleich isn’t a name that many of us remember today but he was a force among Ohio Democrats…McClellan went out of his way to humiliate Schleich and release him from the service. In terms of his perception of the enemy, I think he was working on the best (though seriously flawed) intelligence that was available to him at the time.