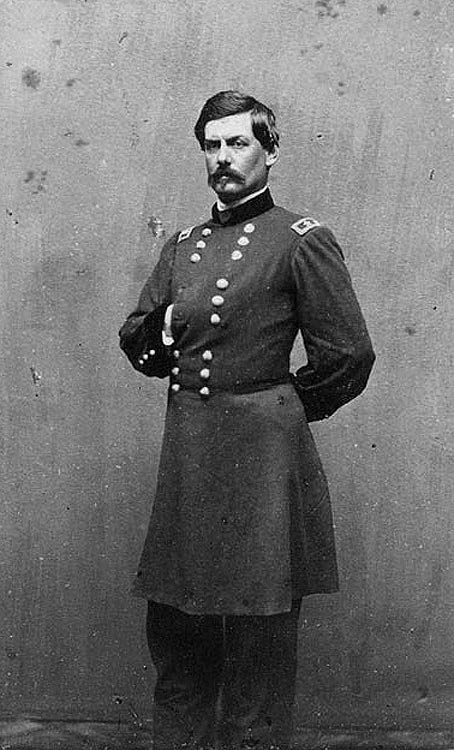

George McClellan in 1861: A Glimpse of Foibles to Come (part two)

We are pleased to welcome back guest author Jon-Erik Gilot

(part two of two)

Yesterday, I outlined some of the ways that George McClellan’s early war actions in western Virginia foreshadowed some of the problems that would become some of his best-remembered if least-desirable traits. Quarreling with subordinates and superiors was one hallmark trait. Micromanaging was another. His micromanagement, in turn, served as a manor contributing factor in another infamous McClellan trait . . .

Slow Movement:

Numerous delays—either real or perceived—would slow McClellan’s movement during the western Virginia campaign and throughout the remainder of his service. He would describe his plan to Col. E. D. Townsend, stating he would not move “until I know that everything is ready, & then…move with the utmost rapidity & energy,” while reassuring his wife, Mary Ellen, that “I shall feel my way & be very cautious.”[1] Historian Fritz Haselberger noted that, between the battle at Philippi on June 3 and McClellan’s advance from Clarksburg to Buckhannon at the end of the month, it had taken McClellan 27 days to advance his army a mere 30 miles to occupy a town that had only been held by the Confederates for a matter of hours. Haselberger estimates that “it was merely a matter of getting up enough nerve to advance and occupy the town” that spurred McClellan’s eventual movement.[2]

McClellan was again slow to move in the face of the Confederates at Rich Mountain. Furious over Schleich’s unauthorized July 5-6 expedition that he feared had tipped his hand, it still took McClellan another five days to move a mere twelve miles ahead of Rosecrans’s July 11 attack at Rich Mountain. Following Irvin McDowell’s defeat at Manassas, General Winfield Scott ordered McClellan to advance down the Shenandoah Valley, to which McClellan responded with reasons why such a movement—which McClellan himself had suggested only days earlier—was impossible, ranging from homesick regiments to incapable officers. McClellan would be criticized for slow movement during some portion of each of his following campaigns; Lincoln referred to it as “the slows.” This sluggish movement can often be attributed to McClellan’s tendency to . . .

Overestimate Enemy Strength:

George McClellan was always outnumbered, or so he thought. While some of this could be chalked up to faulty intelligence, McClellan was apt to overestimate strength and underestimate the abilities of those below him. While his own forces in western Virginia numbered nearly 20,000 men, McClellan would routinely overestimate the strength of the Confederate forces in front of him, believing at one point that up to 50,000 Confederates were headed his direction, when in reality the Confederate strength in the area would muster less than 10,000 effectives. McClellan would estimate Confederate strength at Laurel Hill as high as 10,000, when in reality it was closer to 4,000. Confederates at Rich Mountain were likewise estimated at more than 5,000—the actual number being fewer than 1,500—giving McClellan’s 7,000 men a decided five-to-one advantage.

In the fall of 1861, McClellan would estimate Confederate strength around Manassas ludicrously high at 170,000. Constantly feeling outnumbered, McClellan would wear on the nerves of the Lincoln administration in his continual calls for reinforcements. This stigma would often cause McClellan to exhibit . . .

Indecisiveness:

In the spring of 1861, a civilian railroad director recalled that McClellan “can never make up his mind under two or three weeks on any matter and when he has made it up, is by no means certain about his decision.”[3] While McClellan would exhibit indecisiveness throughout the first campaign, it is nowhere better illustrated than in the face of the enemy at Rich Mountain.

On July 10, with the assistance of local intelligence, McClellan and Rosecrans devised a flanking movement around the Confederate works at Rich Mountain. The plan called for Rosecrans to take his brigade over five miles on a rugged path around the Confederate works, coming out on the Staunton & Parkersburg Turnpike in their rear. At the sound of Rosecrans becoming engaged in the Confederate rear, McClellan would launch a frontal assault on the Confederate works at Camp Garnett.

Rosecrans’s early morning march was more arduous than anticipated, setting back his timetable on the assault, which did not get off until midafternoon. The fight swirled around Rich Mountain for nearly four hours before the Confederate defenders fled over the mountain towards Beverly. Rosecrans had gained position behind the Confederate works at Camp Garnett, located two miles below at the base of Rich Mountain. He had heard no gunfire coming from Camp Garnett, where McClellan was to make a frontal assault. What had happened?

John Beatty of the 3rd Ohio would recall that on hearing Rosecrans become engaged, “General McClellan and staff came galloping up, and a thousand faces turned to hear the order to advance; but no order was given. The General halted a few paces from our line, and sat on his horse listening to the guns, apparently in doubt as to what to do; and as he sat there with indecision stamped on every line of his countenance, the battle grew fiercer in the enemy’s rear. Every volley could be heard distinctly.”[4]

McClellan vacillated on hearing the growing battle. Hearing cheers from the Confederate lines and fearing that Rosecrans had met with defeat, McClellan refused to commit his forces to battle, eventually calling off the retreat and calling his men off the line. Jacob Cox would recall that McClellan “showed the same characteristics which became well known later. There was the same overestimate of the enemy, the same tendency to interpret unfavorably the sights and sounds in battle, the same hesitancy to throw in his whole force when he knew a subordinate was engaged.”[5] Damning commentary from a capable, hard-fighting general.

Historian Russell Beatie picks apart McClellan’s decision-making at Rich Mountain. Beatie relates that “under almost any military circumstances, the first stroke of a flanking force must be immediately followed by the major attack, even a frontal assault against defensive works, or the flanking force will be destroyed and the plan aborted.” Beatie continued, believing that McClellan “drew negative conclusions from inconclusive and incomplete facts that supported by negative and positive inferences . . . McClellan had devised a plan in which he could not see the flanking column and knew his active part would begin on sound. In short, he did not carry out his role as he should have because he refused to make a frontal attack when circumstances demand it.”[6] How many later battles could the same have been said about McClellan?

Conclusion:

If not a benchmark, in hindsight we can at least agree that McClellan’s first campaign set a precedent for future expectations. This is not to say all of his qualities were poor, but that those poor qualities are what would come to define his Civil War service and our popular memory of him.

What do you think was McClellan’s biggest character flaw of the Civil War? What admirable traits did he impart on the Army of the Potomac?

————

[1] Sears, Papers…, 45, 46

[2] Haselberger, Fritz, Yanks from the South (The First Land Campaign of the Civil War: Rich Mountain, West Virginia), (Baltimore, MD: Past Glories, 1987), 159

[3] Beatie, Russell H., Army of the Potomac, Volume I, (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002), 403

[4] Beatty, John, The Citizen-Soldier – The Memoirs of a Civil War Volunteer, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 25.

[5] Cox, Jacob D., “McClellan in West Virginia,” Battles & Leaders of the Civil War., Vol. I , 137

[6] Beatie, 413 – 414.

Another aspect of this period is that while McClellan (via his portable printing press which he took on the campaign and used frequently to let his troops and the public know about his triumphs) took credit for the victories of his subordinates, including Jacob Cox, he was never, as Sears notes, on a battlefield himself. Those victories fed his growing Napoleonic complex as the newspapers styled him the “Young Napoleon.” Cox’s analysis of this in his Reminiscences is apt: “His despatches, proclamations, and correspondence are a psychological study…Their turgid rhetoric and exaggerated pretense did not seem natural to him…He appeared to be in a morbid condition of mental exaltation…he seemed to be composing for stage effect.”

This is highly interesting. While I’ve been aware of some of the general details regarding McClellan’s generalship during this phase of the war, i was not aware of all of these specifics. Regarding the problem of overestimating enemy numbers , some of McClellan’s internet apologists concoct explanations and justifications. That might work for one campaign in isolation, and possibly two if we’re being inordinately generous. But not every time. “Fool me once …” McClellan also was prone to creative math regarding his own numbers once his often-absurd wartime estimate of the enemy were later thoroughly debunked. For example, there’s the matter of his own strength for the Seven Days, which diminished considerably between his August, 1863 official report and his B&L article some 20 years later.

Mr. Foskett I think you hit the nail on the head. The numbers he used for both opposing armies and his work consistently obnoxiously false. My final straw with young Napoleon came while reading Sears book on the Peninsula Campaign. After his change of Base for lack of a better term he simply boarded one of the Navy ships and had dinner and left no orders for any of his subordinates as they were being pushed literally back into the river. I know you can’t diagnose somebody 160 years later but I honestly believe he had some sort of Mental Health condition. He believed he was always being persecuted, you believe the world was out to get them, believe he was sent by God to save the Union- these are all conditions of somebody suffering from severe manic episodes. Great article

The entire episode during the crucial June 30 fighting at Glendale showed another aspect of McClellan’s “command style” (I’m putting it in neutral terms) which made him unsuitable in that role. There have been strenuous efforts on the internet by some of his more extreme advocates to cobble together isolated facts, assumptions, and theories to “explain” how in fact he actually exercised effective command and control in that battle despite being nowhere near the fighting, despite failing to put any of his subordinates in overall, coordinated command in his stead, and despite his subordinates confirming afterwards that there was no directing hand. They all fall well short.

Regarding his assessment of his own numbers for the Seven Days, it appears that he was using PFDE or some equivalent in his official 1863 report (which was well before it became irrefutable after the war that his estimates of Lee’s strength were sheer fantasy). This would have put his own numbers at above 90,000. Twenty years later, after everyone knew that Lee never had anything remotely close to the absurd 180,000 – 200,000 McClellan had reported to Washington at the time, he significantly deflated his own numbers by some 20,000.

Well said Mr. Foskett, I could’t come up with the right words that you were able to so eloquently. This blog, as you know obviously is run very proffessional and respectfuly while allowing different opinions and I really admire that and never want to cross the line. But when I look at his whole body of work i’m clueless as too how anyone can think he’s even a average general.

The irony is that even I think he may well have done a good job in the position which Halleck ended up holding – dealing with strategic decisions, logistics, etc. The big hurdle would have been his inflated ego, because even that position would have been subject to civilian control (Lincoln and Stanton, primarily). Unfortunate, because he likely had those skills.

Great point between building up the army of the Potomac his management skills and developing and setting up the most efficient Railroad would lead you to believe he would have been perfect for the aforementioned position you mentioned. I believe though his mental defect would have got in the way of any thing he did. He was a man who believed he was incapable of making a mistake while those around him were complete idiots. Great conversation Mr.Foskett, your points were spot on and taught me something. Have a great holiday and I hope to talk to you again soon!

Thanks, and you as well.