Ironclad Superweapons of the Civil War: USS Monitor and CSS Virginia

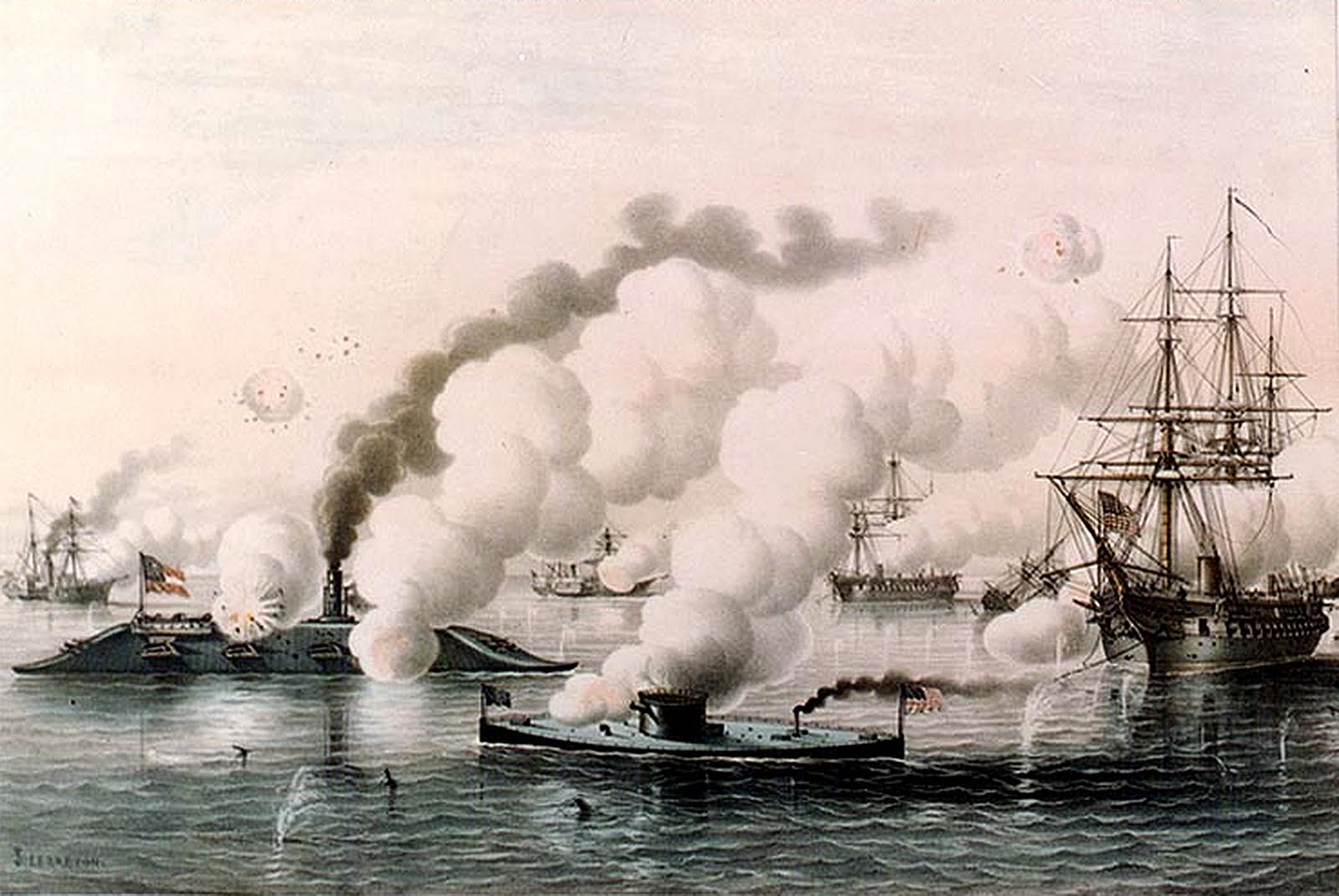

The clash of the ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia in Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862 is considered a revolutionary event in naval warfare, but neither vessel quite lived up to the ambitious expectations of its sponsors.

On a hot August day in 1861, the new Secretary of the United States Navy, Gideon Welles, met with fellow Connecticuter, Cornelius S. Bushnell, at the Willard Hotel across from the White House. Welles handed over a copy of draft legislation directing construction of armored ships and floating batteries.

Congress was sitting in special session called by President Lincoln to approve the raising of troops and committing of funds to suppress the rebellion. Welles was anxious that his bill also be passed. Bushnell, an influential railroad executive and shipbuilder from New Haven, agreed to promote the matter with contacts in the House of Representatives.

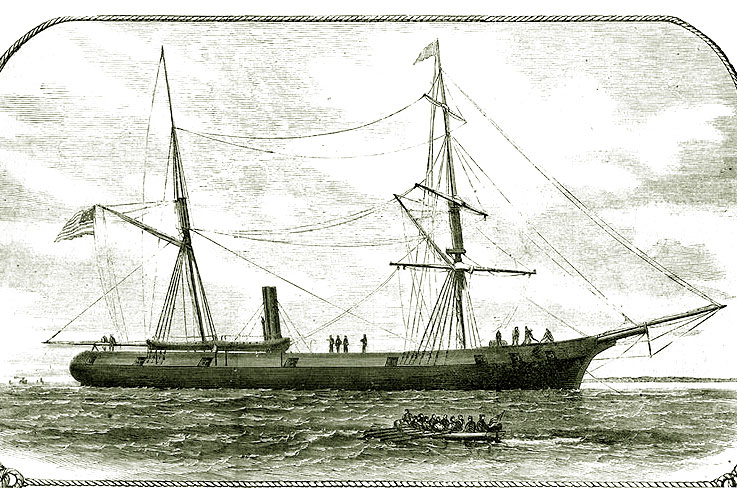

Welles perceived a dire threat from Confederate ironclads already being constructed in Norfolk, Mobile, and New Orleans. He was particularly worried about the former USS Merrimack. The once-powerful frigate had been partially burned and scuttled when the navy abandoned the Gosport Navy Yard near Norfolk, Virginia, the previous April.

The ship now was under furious repair in the Gosport drydock, being clothed in iron armor, and renamed the CSS Virginia. Despite Rebel efforts to keep the project secret, the secretary had, “contrived to get occasional vague intelligence of the work as it progressed.” His own government, however, “was wholly destitute of iron-clad steamers or floating batteries.”[1]

A letter from, “a distinguished citizen of Massachusetts” was entered into the Congressional record supporting the secretary’s proposed legislation. Mr. E. H. Derby wrote, “in reference to mail-clad [ironclad] steamers—a subject which he has thoroughly examined.”

Derby urged the absolute necessity for acquiring such vessels, and, “that neglect of this opportunity will expose us to serious losses, obloquy, and disgrace.” The British had tested and confirmed that 4.5-inch iron plates were impervious to shot and shell even from the best Armstrong and Whitworth 100-pounder cannon. They had ceased building wooden ships-of-war altogether.

“England and France will, by the close of this year, have twenty to thirty iron-clad steam ships, each of which could pass into Boston or New York with impunity, and possibly destroy either city. Unless we have means to meet them, France and England may be able to dictate terms as to the southern blockade. With such steamers we can, with little or no loss, recover Charleston, Savannah, Pensacola, Galveston, Mobile, and New Orleans…. [I] trust you will grasp a weapon so essential to our country at this moment.”[2]

Senator James Grimes of Iowa also argued in favor of the bill: “We need a more effective blockade…. Scoundrels North, as well as scoundrels South, are carrying on an unlawful trade in fraud of our revenue.” Pirates and sea rovers must be captured; Southern harbors and forts must be retaken; commerce must be protected, and Northern harbors defended.

“Suppose England, in her love for cotton, should forget the duties which she owes to mankind and attempt to break our blockade, and we should get into trouble with her: what is to become of our northern cities and our cities upon the coast?” New York harbor is defenseless against the navies of Great Britain or France. “I want to protect [my country] and to preserve it in all its parts.”[3]

Congress passed, and Lincoln signed, the Welles legislation. The secretary was directed to appoint a board of “three skillful naval officers” to investigate plans and specifications for constructing armored ships and floating batteries, and upon their recommendation, to cause them to be built. The bill appropriated for that purpose $1,500,000.[4]

Cornelius Bushnell submitted his own design to the board for a standard wooden-hulled broadside frigate with iron plating added. Concerned about the vessel’s stability under the additional weight of armor, Bushnell was advised to consult John Ericsson, a highly-regarded Swedish engineer residing in New York.

Ericsson reassured Bushnell about the viability of his planned ironclad; Bushnell’s plans would be accepted and eventually become the USS Galena. (Galena was, however, widely regarded as a failure due to the thinness of armor plate. She suffered serious damage at the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff near Richmond in May 1862.)

Ericsson then surprised Bushnell by asking him to examine Ericsson’s own model for, “a floating battery absolutely impregnable to the heaviest shot or shell,” called Monitor. Ericsson explained, “how quickly and powerfully she could be built.” He proudly exhibited a medal and letter of thanks from Napoleon III, who had considered a similar plan during the recent French war with Russia, but had not acted on it.

Bushnell was delighted with the model, taking it—with Ericsson’s permission—immediately to Hartford where Welles was vacationing. As Bushnell recalled, he “astounded” the secretary by saying that now the country was safe; he, “had found a battery which would make us master of the situation so far as the ocean was concerned.”[5]

The model, “impressed me favorably,” recalled Welles, “as possessing some extraordinary and valuable features, tending to the development of certain principles, then being studied, for our coast and river blockade, involving a revolution in naval warfare.” He urged Bushnell to lose no time in presenting the plan to the Naval Board in Washington.[6]

Through New York contacts—who happened to be large manufacturers of iron plate—Bushnell connected with former New York governor and now Secretary of State William Seward, who in turn provided “a strong letter of introduction” to the president. Lincoln, ever interested in new gadgets, “was at once greatly pleased with the simplicity of the plan and agreed to accompany us to the Navy Department at 11 A. M. the following day, and aid us as best he could.”

Promptly as scheduled, Bushnell and the president met with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox (Welles had not yet returned from Hartford) and members of the board. “All were surprised at the novelty of the plan. Some advised trying it; others ridiculed it,” wrote Bushnell.

The conference closed with Lincoln remarking, “All I have to say is what the girl said when she put her foot into the stocking, ‘It strikes me there’s something in it.’” After intense discussions, the board approved the plan and Ericsson began construction, with orders to complete it before Virginia could raise havoc.[7]

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory also had grand visions for his new weapon. He wrote to Virginia’s commander: “Could you pass Old Point [Comfort] and make a dashing cruise on the Potomac as far as Washington, its effect upon the public mind would be important to the cause.”[8]

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory also had grand visions for his new weapon. He wrote to Virginia’s commander: “Could you pass Old Point [Comfort] and make a dashing cruise on the Potomac as far as Washington, its effect upon the public mind would be important to the cause.”[8]

A following letter inquired: “Can the Virginia steam to New York and attack and burn the city?” Presuming good weather and smooth seas, Mallory did not doubt she could destroy the Brooklyn Navy Yard with its magazines, all the lower city, and much shipping.

“Such an event would eclipse all the glories of the combats of the sea….” Bankers would withdraw their capital from the city. The enemy could never recover. Peace would inevitably follow. “Such an event, by a single ship, would do more to achieve our immediate independence than would the results of many campaigns. Can the ship go there? Please give me your views.”[9]

It was not to be. Neither the USS Monitor nor the CSS Virginia were capable of becoming, “master of the situation so far as the ocean was concerned.” Neither they nor their successors were going to range up and down the coasts conquering cities and defeating enemy fleets; they could hardly poke their noses out of shallow and sheltered waters.

The two fought to a tactical draw in Hampton Roads (the strategic outcome is still debated). Monitor almost sank on its way to the battle and did sink in a storm off Cape Hatteras, December 31, 1862. Virginia was blown up by her own people to avoid capture, May 11, 1862. But both spawned classes of ironclads that, despite severe shortcomings, played important roles in the war. Their places in history are assured.

The two fought to a tactical draw in Hampton Roads (the strategic outcome is still debated). Monitor almost sank on its way to the battle and did sink in a storm off Cape Hatteras, December 31, 1862. Virginia was blown up by her own people to avoid capture, May 11, 1862. But both spawned classes of ironclads that, despite severe shortcomings, played important roles in the war. Their places in history are assured.

Note: This post was extracted from a forthcoming book for The Emerging Civil War Series, With Mutual Fierceness: The Battle of Hampton Roads.

[1]Gideon Welles, “The First Iron-Clad Monitor,” in The Annals of The War Written by Leading Participants North and South (Philadelphia, 1879), loc. 106, 147 of 15999, Kindle.

[2] John C. Rives, The Congressional Globe: The Debates and Proceedings of the First Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress (Washington, 1861), 210.

[3] Ibid., 256-57.

[4] Ibid., 217.

[5] C. S. Bushnell, “Negotiations for the Building of the ‘Monitor,’” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series.” Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, of the Editorial Staff of “The Century Magazine” 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 748.

[6] Welles, “The First Iron-Clad Monitor,” loc. 120-123 of 15999, Kindle.

[7] Bushnell, “Negotiations for the Building of the ‘Monitor,’” in Battles and Leaders, vol. 1, 748.

[8] S.R. Mallory to Flag-Officer Franklin Buchanan, February 24, 1862, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922) (Hereafter cited as ORN), Series 1, vol. 6, 776-777.

[9] S.R. Mallory to Flag-Officer Franklin Buchanan, March 7, 1862, in ORN, Series 1, vol. 6, 780-751.

1 Response to Ironclad Superweapons of the Civil War: USS Monitor and CSS Virginia