Confederates Invade San Francisco?

Shortly before his death in 1886, James I. Waddell, former captain of the CSS Shenandoah, wrote in his memoirs: “I had matured plans for entering the harbor of San Francisco and laying that city under contribution.”[i]

Waddell never did pass through the Golden Gate, but he came close. He and his ship were notoriously hated in the city by the bay; San Franciscans tried and partially succeeded in exacting revenge.

Shenandoah was one of the most successful of Confederate commerce raiders, the only one to circumnavigate the globe. While the war struggled to conclusion and the nation began to bind its wounds, these Rebels invaded the north—the deep cold of the Bering Sea between Alaska and Siberia—and captured 26 Yankee whalers. It was June 1865.

They fired the last gun of the Civil War, ten weeks after Appomattox, set the land of the midnight sun aglow with flaming enemy vessels, and almost became trapped by ice. This was an unprecedented accomplishment that a few months before would have been greeted with jubilation in the South and despair in the North. Waddell crammed all the hundreds of men from the destroyed ships onto four of the oldest and slowest whalers and sent them off to San Francisco.

Confederates also captured newspapers from San Francisco via Hawaii dating as late as the previous April 17, informing them of Lee’s surrender and Lincoln’s assassination. The Southern government had fled Richmond said some papers, but others stated that Lee had joined General Johnston in North Carolina for an indecisive battle against General Sherman.

The news also carried an impassioned proclamation by President Davis—issued on the run from Danville, Virginia—announcing that the war would be carried on with renewed vigor and exhorting his people to bear up heroically. Months later and half a world away, Shenandoah Rebels took this to heart. They were very worried, but not about to believe all the Yankee propaganda, that their cause was lost, and their sacrifices for naught.

First Lieutenant William Whittle had anticipated the loss of Charleston and Savannah, and even the evacuation of Richmond once Wilmington was gone, but not Lee’s reported surrender. “All this last I put down as false…. I do not believe one single word.” Ship’s Surgeon, Dr. Charles Lining: “I was knocked flat aback. Can I believe it? And after the official letters which are published as being written by Grant & Lee, can I help believing it?”[ii]

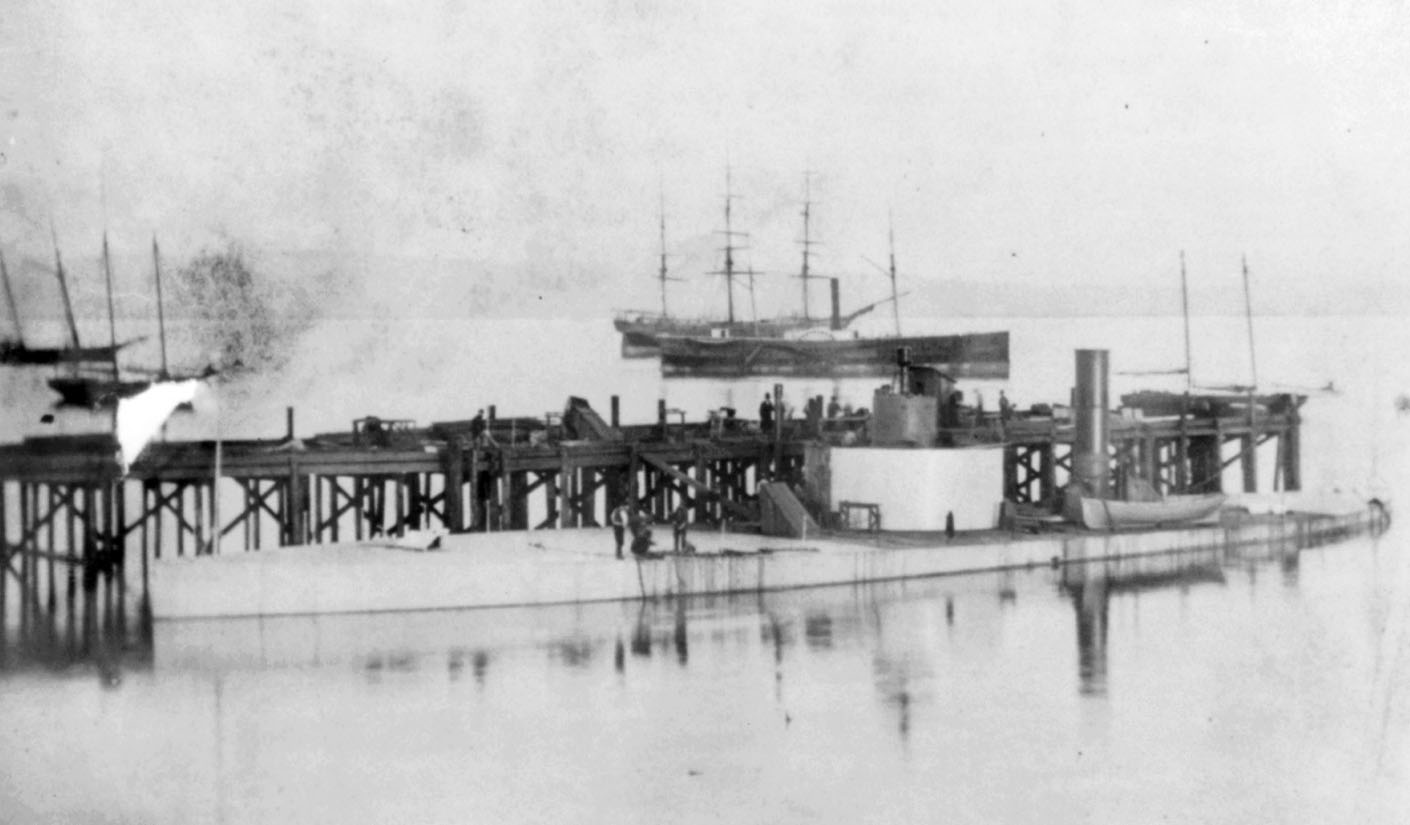

By mid-July, Shenandoah was finally headed south, bowling along eight hundred miles out in the Pacific near the latitude of San Francisco. The captured newspapers had reported only one warship present in the bay: the USS Comanche, a Passaic-class monitor armed with two powerful XV-inch Dahlgren smoothbores.

Comanche had been constructed in New Jersey, disassembled, shipped around the Horn in a sailing ship, and reassembled. She was the only ironclad on the coast. The remainder of the sparse Pacific Squadron was spread up and down the rim of Central and South America, primarily protecting the approaches to Panama. In his memoirs, Waddell described his plans.

Comanche was commanded by Lieutenant Commander Charles J. McDougal, an “old, familiar shipmate” of Waddell from before the war. McDougal was “fond of his ease.” He was no match for any Shenandoah officer “in activity and will.”

It would be easy enough, continued Waddell, to enter the harbor at night, ram a surprised Comanche, overwhelm her decks and hatches with armed borders, and take control without loss of life. “E’er daylight came, both batteries could have been sprung on the city and my demands enforced.”[iii]

The practicality of such a scheme can be seriously doubted; San Franciscans were not known for shyness in the face of a good fight. But whatever Shenandoah’s captain was thinking at the time about invading the city, he apparently did not share these ideas with his officers. Other than the final writings of an ageing warrior, this plot is nowhere mentioned in contemporary sources, including several detailed officer cruise journals, letters, memoirs, and Waddell’s own extensive, immediately post-war report.

Waddell did claim in his post-war report an intention to run along the coast with the north wind sweeping down Lower California, keeping a sharp lookout for enemy cruisers and for gold packets on the Panama to San Francisco run. Some of his officers were itching to take a fat clipper on its way to or from the Orient.

However, as Midshipman Mason confided to his journal, Shenandoah’s actual course took them too far off the coast to meet mail steamers and nowhere near the San Francisco to Hawaii and China trade routes. Waddell seemed determined to get around the tip of South America as quickly as possible without seeking more captures, which would be just a matter of luck along this track. “The skipper of course must know best, but I think we might make the attempt.”[iv]

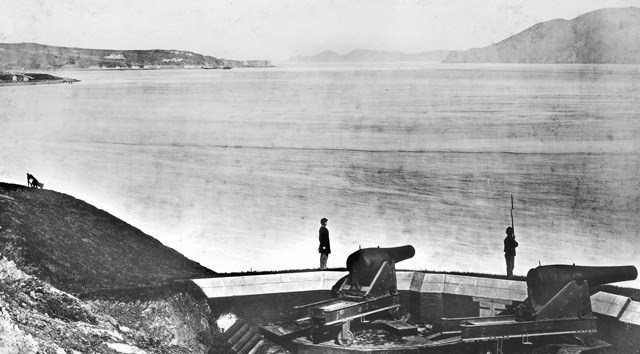

The denizens of San Francisco, meanwhile, were very aware and acutely worried about the Rebel raider, but they had no idea where in the wide ocean she was. They had heard nothing since Shenandoah’s visit to Melbourne six months previously.

Then on July 20, the old whaler Milo staggered through the Golden Gate with two hundred refugees from the Bering Sea. “Wholesale Destruction of American Whalers,” trumpeted the San Francisco Bulletin. “Probable Destruction of Another Fleet of Sixty Whalers.” “The most extensive and wholesale destruction of American shipping yet committed by any rebel pirate since the beginning of the war.”

“Great apprehensions felt by mercantile community of San Francisco,” reported the commandant of the Mare Island Navy Yard to Navy Secretary Welles. Merchant ship owners and underwriters requested authority to charter, arm, and man the fast Pacific Mail Company steamer Colorado–the only available vessel capable of catching the swift Rebel–to pursue Shenandoah. (They would receive the authority a month too late.)[v]

On July 22, the Sacramento Daily Union reported a conversation in a bar with sailors of the American bark Mustang, which had recently returned from Melbourne. On a quiet night the previous February, Shenandoah had been lying placidly at anchor in the dark Australian harbor.

These sailors had, so they said, rowed a boat silently over to the Rebel vessel until the huge black hull, towering masts, and tracery of rigging loomed above, blotting out shore lights. At the end of a line behind the boat floated a cask containing 250 pounds of black powder with a cocked revolver and cord attached.

Only occasional soft voices and steps of the watch on deck disturbed the sleeping vessel. The intruders secured the cask to the hull with a chain and rowed away, intending to pull the cord and detonate the deadly device from a distance. But the chain broke, aborting the operation.

Had this attempt to blow up the warship with a “torpedo” succeeded, the irony would have been manifest as one of the Confederacy’s most innovative weapons was turned against it. Given Shenandoah’s high state of alert at the time against just such dangers, one can question that the affair occurred exactly as related. But the sentiment was genuine and this or something like it must have been contemplated by more than one group of enraged Yankees.[vi]

On August 2, Shenandoah encountered the English bark Barracouta, thirteen days from San Francisco bound for Liverpool with newspapers only two weeks old confirming that their country had been overrun, president captured, armies and navy surrendered, the people subjugated. “The darkest day of my life,” wrote Lieutenant Whittle in his journal. “The past is gone for naught—the future is dark as the blackest night. Oh! God protect and comfort us I pray.”[vii]

Waddell struck the guns below, assumed the guise of an unarmed merchantman, and began a long run around the Horn. November 6, 1865: Shenandoah limped into Liverpool. Captain Waddell lowered the last Confederate banner without defeat or surrender and abandoned his tired vessel to the British.

Hatred for James Waddell in San Francisco lingered long after the war. By 1875, he had resumed full American citizenship and was engaged by the same Pacific Mail Company to command its newest liner, the 4,000-ton steamer City of San Francisco on its maiden voyage from that city to Sydney via Honolulu.

San Francisco papers carried angry editorials decrying the potential presence of a Confederate marauder in the city. Mobs of whalemen threatened violence over losses suffered a decade earlier. Amidst the uproar, City of San Francisco sailed with a substitute captain. Waddell assumed command on a later voyage.

James Waddell and the people of San Francisco were not fated to meet either as enemies or as countrymen, but they certainly influenced each other.

[i] James D. Horan, ed., C.S.S. Shenandoah: The Memoirs of Lieutenant Commanding James I. Waddell (New York: Crown Publishers, 1960), 175.

[ii] Dwight Sturtevant Hughes, A Confederate Biography: The Cruise of the CSS Shenandoah (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2015), 170.

[iii] Horan, ed., C.S.S. Shenandoah, 175.

[iv] Hughes, A Confederate Biography, 185-186.

[v] McDougal to Welles, July 23, 1865, in The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1896), 3, 1:571.

[vi] “Sacramento Daily Union,” Volume 29, Number 4472, July 22, 1865.

[vii] William C. Whittle, Jr., The Voyage of the CSS Shenandoah: A Memorable Cruise (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005), 182.

Shenandoah stories are always entertaining ! Thanks.