Survival at Sea: A Terrifying Voyage to the Peninsula

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

When he volunteered for the U.S. Sharpshooters (U.S.S.S.) in 1861, George A. Marden knew well there were many ways he could perish while serving the Union cause. It’s unlikely, however, that he ever imagined he might die at sea. But drown the 22-year-old soldier from New Hampshire nearly did, far offshore in Chesapeake Bay, on a ship en route to the Peninsula Campaign.

The event occurred on March 29, 1862. The steam-driven tug on which Marden traveled, the West End, was carrying Army of the Potomac troops and horses, and towing 85 additional men and supplies in two barges. The vessels were off the Virginia coast and journeying south, from Alexandria to Ft. Monroe. Caught in the bay by a storm, they were blown away from land and pounded by increasingly stronger winds and larger waves. The tug and its passengers eventually weathered the ferocious gales and reached safety, he wrote, “only by the grace of God,” the badly-rattled soldier wrote in a Mach 30 letter to his family. However, Marden continued, he had come ashore believing that a desperate measure taken by the tug captain to save his crew and passengers very likely had led to the deaths of those travelling in the barges.[i]

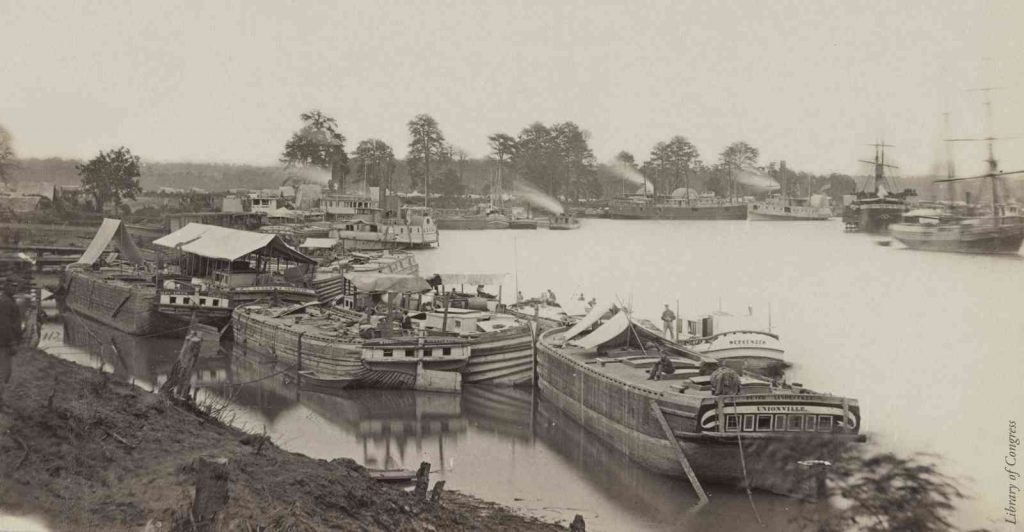

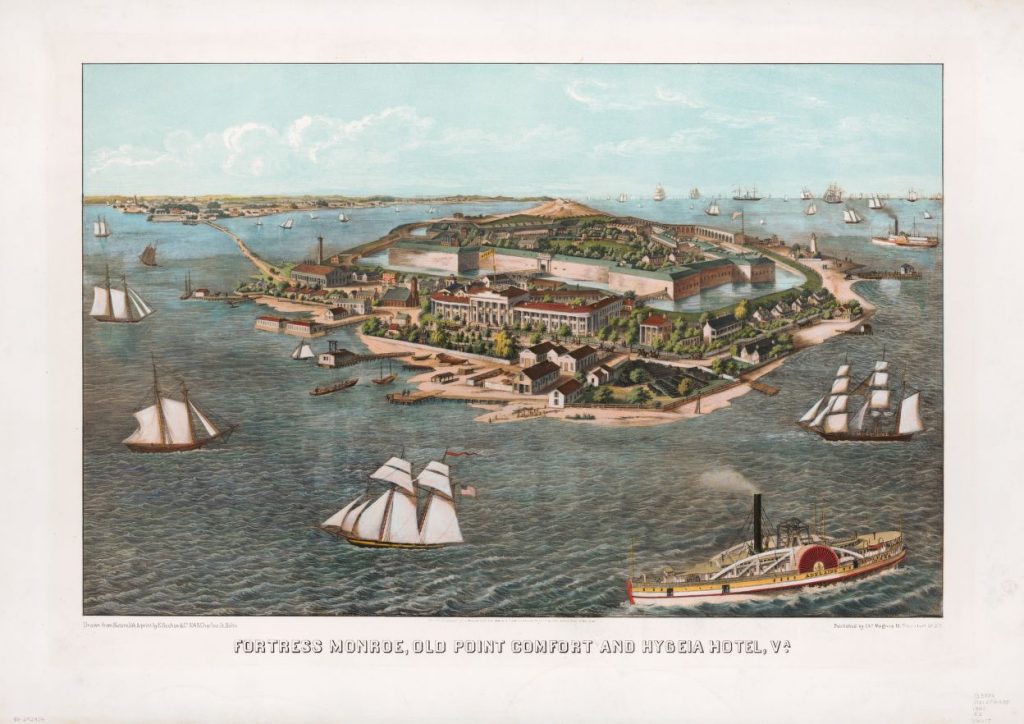

When the storm struck, Marden and his Army of the Potomac comrades were traveling 170 miles south to participate in what would become known as the Peninsula Campaign. Their tug and the barges it pulled were part of a flotilla of nearly 400 mostly civilian ships and towed transports that, between March 18 and mid-April, carried more than 120,000 federal soldiers and their horses, ordnance and supplies to Ft. Monroe. The army massed around the well-defended Yankee stronghold, built on the point where the James River and Hampton Roads meet the Chesapeake Bay. From there, in early April, the federal troops planned to march up the peninsula for 75 miles, eventually attacking the Confederate capital, Richmond. The vast and complex operation— popularly referred to in the North as the “grand campaign”— was conceived by Maj. Gen. George McClellan, the Army of the Potomac’s commander. It was larger than all previous seaborne American military expeditions and would not be surpassed in size or scope for the Civil War’s duration.[ii]

Marden had joined the U.S.S.S. the previous November. Promoted to sergeant in January while training at his Camp of Instruction in Washington, D.C., the soldier was transferred from the 2nd to the 1st Regiment and assigned as an aide to his regimental command. The unit was attached to the army’s Third Corps.

Administrative matters delayed the sergeant’s departure for the peninsula. By the time he and his horse crowded aboard the West End on March 27, most of the 1st Regiment already had boarded a passenger steamship and sailed to the peninsula, leaving in a convoy of 22 vessels, in the midst of the pageantry of bands playing and booming cannon salutes. Marden’s mode of transport was considerably less luxurious. “I am not on board much of a craft,” he wrote in a letter composed while sailing down the Potomac, complaining there was “no guard rail around the deck, no cabin and nothing for comfort.” There was no cooking on board. The men chewed hardtack and sausage. His fellow passengers included several quartermasters, who were forced to share a horse stall as their cabin. The quarters the sergeant staked out were only slightly better: his bed was a coal heap in the engine room.[iii]

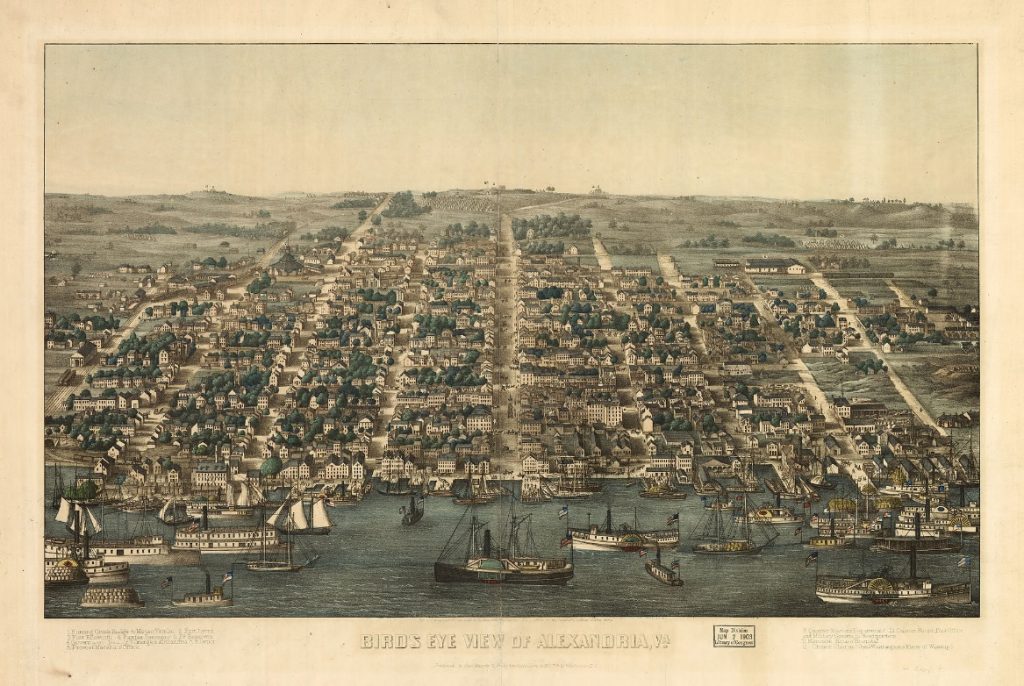

The little tug’s departure from Alexandria lacked the formality and grandeur his Sharpshooter comrades on the Emperor had enjoyed. Pulling a long chain of barges, the West End wove onto the Potomac River through a harbor that Marden described as crowded with “steamers, canal boats, tugs, schooners, ships, barges and almost everything in the shape of a vessel you could think of except a Chinese Junk.”[iv]

The trip to Ft. Monroe on the tug, as Marden related it, was trouble-free while the vessels cruised down the Potomac. At one point, a barge picked up two runaway slaves from inland Virginia who were floundering as they attempted to paddle across the river to Maryland in a wooden crate.[v] The conditions changed as the tug steamed into a windy Chesapeake Bay on March 28th and was forced to anchor near shore for the night. The wind persisted in the morning, prompting the captain to leave all but two of his barges at anchor, so they could await another tow vessel and better weather. In his letter, the soldier related the ordeal that followed as the tug continued onto the bay.

The wind blew fresher and fresher and we got no nearer [to shore]. The wind increased and the waves began to sweep across the decks. We made no headway with our barges and nobody knew where we were. The pilot said if we would drop the barges he would go to Old Point [and on to Ft. Monroe]. The Quartermaster declared if we kept on we were all lost but if we followed him we would all go right.

Marden, who had monitored worried discussions about the tug’s predicament, reported the consensus reached. “One thing became certain, the barges must be let go or all would go to the bottom,” he wrote. “They [on the barges] were as well off without us as with us.” The soldier’s troubled account of what then happened follows. (For easier reading, I have added paragraph breaks.)

I hated to leave the poor fellows. One [vessel in tow] was an old canal boat and the other a barge with 85 men on board. The water was very deep and anchoring was doubtful. Just then we saw a steam ship bearing off to the southwest. The whistle [on the tug] screamed and the colors were turned union down as signals of distress. The steamer took no notice of us.

We then let them [the barges] go. I could hardly help crying as we were afraid we would never see them again. It seemed like throwing them all overboard. The waves were boiling like a huge cauldron, and the wind blew like a hurricane. No land was to be seen but the Va. shore about 15 miles distant… After casting off we went on not knowing where we should turn up. I had nothing to eat all day.”

The pilot kept away to the East and the Quartermaster swore that we would be out to sea if the tug held together. The Capt. didn’t know what to do, one or two men kept bawling to turn about and do as the Quarter Master said. I kept quiet and wished myself in New Hampshire, or at least somewhere on terra firma. I concluded that those who go down to the sea in ships might go for all men, but I didn’t enlist to join the marines. I wouldn’t have been frightened but the Capt., Pilot and crew said it was a doubtful case, and I thought they ought to know…”

The captain stayed his course, and Marden wrote that the crew eventually “saw a light ship then the Old Point light then the light of Fortress Monroe and we knew we were all right.” The tug steamed into the harbor and anchored about seven p.m. The vessel lay there the night, “rolling like a cockle shell,” while the soldier tried to sleep on his coal heap, as he would share in a later letter, haunted by images of the storm and the drifting barges.

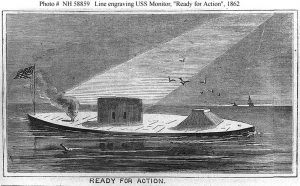

The morning of March 30, Sgt. Marden stepped onto the boat’s deck and into the early light for his first view of the harbor and Ft. Monroe. Before him lay the U.S.S. Monitor, moored just 100 yards away. Although awed by the ironclad’s recent standoff against the C.S.S. Virginia— the armored gunboat better known to northerners as the Merrimack— the soldier was underwhelmed by the Monitor’s unconventional appearance. “I could only compare her to a raft of logs with a scalding tub in the middle,” he wrote.

After going ashore on March 30, the Sharpshooter and some of the other soldiers from the tug stayed the night at the Hygeia Hotel, just outside Ft. Monroe’s walls. The next day he rode to Camp Porter, four miles outside the fort, to join his regiment. In a letter written from his camp that night, Marden shared the welcome news that he’d learned at the hotel that a Union gunboat on Chesapeake Bay had encountered both of the drifting barges, saving them from “falling into Secesh hands or lying over.” That was not before the 85 men on board had spent an afternoon and an entire night, adrift in stormy waters, “spewing, praying and crying.” Some of the soldiers, he was told, came ashore at Ft. Monroe “angry enough at the [tug] Capt. and thinking to shoot him.”[vi]

At Camp Porter, Marden joined his 1st Sharpshooter comrades in preparations to march “on to Richmond” with other Third Corps regiments and divisions. Their progress soon would be stymied by Confederate fortifications at Yorktown, built on the Revolutionary War battlefield where, in 1781, the British surrender to the Continental Army concluded the long fight for American independence.

George Marden’s prayers to escape from the storm and to stand “somewhere on terra firma” had been answered. Just six days after he had reached safe harbor, however, the soldier and his regiment would be at Yorktown, under fire from Confederate gunners and marksmen and engaged all day in some of the first combat of the Peninsula Campaign.

Sources:

[i] The Civil War letters of George Marden, March 30, 1862, archived at Rauner Special

Collections Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover N.H. (Unless otherwise noted, all other Marden quotes come from his March 30 letter.).

[ii] Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992) pp. xi, 22-24).

[iii] Marden, March 27, 1862

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Marden, March 31, 1862

Wonderful article!