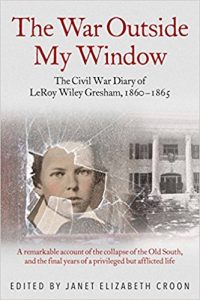

Book Review: “The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Diary of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865”

n

Let me say right up front that The War Outside My Window is NOT the feel-good book of 2018. In fact, it is just the opposite. The war is lost, the boy dies, and animals are harmed in the passing of this time period in Georgia. Nevertheless, with a cup of good coffee and a positive attitude, it is one of the most interesting books published in a long time.

Let me say right up front that The War Outside My Window is NOT the feel-good book of 2018. In fact, it is just the opposite. The war is lost, the boy dies, and animals are harmed in the passing of this time period in Georgia. Nevertheless, with a cup of good coffee and a positive attitude, it is one of the most interesting books published in a long time.

This book is the diary of LeRoy Gresham, the youngest son of an affluent slaveholding family in Macon, Georgia. He was twelve years old in 1860, and an invalid due to a combination of a serious leg injury from a fallen chimney that crushed his leg and skeletal tuberculosis, specifically Pott’s disease. Google up some images of this affliction and you will get a good idea of the misery that was a daily companion to this bright, inquisitive, witty, well-read, and sensitive young man.

LeRoy began keeping his journal on June 12, 1860, with a very mundane entry: “Mother has gone to the serving society.” As time continued, he began to find his own, very authentic voice. The diary is not a series of maudlin, self-pitying entries. Rather it is a view of the South from the beginning to the end of the Civil War, as Macon reacted to secession and gathered men for volunteer soldiering (in a state with a governor who did not necessarily want to send them), until the surrender at Appomattox and beyond. Interwoven among the usually inaccurate news reports, Leroy gave evidence of his deteriorating physical condition. This amazing young man who read Greek and Roman classics along with Shakespeare and Dickens, loved math and solving puzzles, and played chess on a very high level, lay in his bed and observed the collapse of his world. To relieve the tedium of dying, his family somehow came up with a cart or small wagon to relieve his bedridden condition. A relative or more often, a young slave, pulled him around town so that LeRoy could immerse himself in the goings-on of the day.

News came in the form of newspapers, letters, and gossip. The reader will be struck with the military inaccuracies, especially as to casualty counts. Young LeRoy read every newspaper he could get and bemoaned the diminishing sources of current news as the war went on. His immediate family was impacted directly. His older brother, Thomas, served in Lee’s army in Virginia and many others in the extended group of family and friends served as well. The home front deteriorated, as evidenced by the actions of LeRoy’s mother and sister. New bonnets were made of palmetto, and dresses were repurposed in order to attend local gatherings and church. Homespun cloth was sent up from the family plantations along with meat and vegetables for the table, and to share among the less fortunate.

LeRoy wrote about everything, from social events to family matters. Deaths (many), weather (hot or raining, it seemed), and his pets were recurring topics. He named his various dogs for Confederate generals, but most were ill-behaved and ended up changing ownership. His declining health was addressed regularly, and the reader gets a solid look at family medicine in the 1860s. LeRoy’s parents could afford the very best for their son, but without an understanding of germs or disease, most of the efforts of doctors did little to alleviate his discomfort or alter the progression of his disease. Both the Preface and the Appendices have detailed accounts of how editor Janet Elizabeth Croon, publisher Theodore P. Savas, and Dennis A. Rasbach, MD, FACS worked to solve the mystery of LeRoy’s diagnosis. His care is analyzed piece by piece and compared to modern medicine, making for fascinating, if painstaking, reading. LeRoy wrote: “I am weaker and more helpless than I ever was . . . I have been sick with a pain in my back and heart all day . . . Saw off my leg.” He did not realize until the very end of his life that he was dying, and the reality of this came as a shock to young LeRoy.

Editor Janet Croon, an educated educator in her own right, has given the reader much more than just a glimpse into the past. The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Journal of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865 presents the compelling story of a doomed young man of white privilege who was dying at exactly the same time the southern dream of an independent Confederacy was dying. Eventually, both fail. Without the efforts of Croon, Savas, and Rasbach, LeRoy Gresham’s voice, which speaks as powerfully to us from the past as does that of Anne Frank, would have continued to be unheard. Readers will remember LeRoy long after the covers of the book have closed. As sad and difficult as this book is to read, it is definitely an important addition to the understanding of the Southern home front.

Janet Elizabeth Croon, Editor–The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Diary of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865

Savas Beatie, LLC, 2018

480 pages

8 pages of previously unpublished photographs

Publisher’s Preface, Introduction, Medical Forward, Dramatis Personae, LeRoy Wiley Gresham Obituary, Postscript, Medical Afterwords, Appendix, Note on Sources, Acknowledgements, Index, Maps and Illustrations

* * *

The galley copy I reviewed was a bit different from what the actual finished product will be–this happens in publishing. The book will include a seven-page letter from LeRoy’s beloved mother to her sister about losing her son that is both informative and heart-breaking. Dr. Dennis Rasbach has also written an accompanying digital book, “I am Perhaps, Dying,” which treats the medical aspects of LeRoy’s condition in greater detail.

Savas Beatie is offering signed first editions, and people can contact SB at sales@savasbeatie.com to reserve a copy or call916-941-6896 and speak to Stephanie to place an order. Payment is due before shipment.

What a good review! Thank you Meg.

I read a pre-publication edition. Apparently the final book will have even more information about the treatment of a disease such as the one LeRoy sufferred from, and even more maps. This one is a winner. I hope SB considers putting it out to the classroom reading market.

Meg, many thanks for this outstanding review. I wanted to add a couple things.

The finished book is 480 pages (rather than 401) and it includes 8 pages of mostly unpublished photos. There is a 7-page letter from his mom to her sister about his death (not in the galley) that is informative and heart-breaking.

Dr. Dennis Rasbach has also written an accompanying digital book “I am Perhaps Dying,” which treats in depth the medical aspects of LeRoy’s condition.

We are offering signed first editions, and people can write us at sales@savasbeatie.com to reserve a copy (you can pay for it when it is ready to ship) or call 916-941-6896 and speak with Stephanie to place it.

This is one of the most satisfying, and sad, projects I have ever worked on. I am so glad you liked it.

Ted Savas

Savas Beatie LLC

I added these comments to my review. Looks like another SB winner. Seems over half of what I reiew are SB–Huzzah!

Thank you, Meg. It is the most unique thing I have ever seen or worked on. I am glad you enjoyed it.

excellent — had not heard of this — will definitely buy it when it comes out

It is certainly not a red lines-blue lines book. It gets to the literal heart of what makes the Confederacy so appealing–its people and their hopes for independence.

Meg, Thank you for your fine review. I think you have done an excellent job of capturing the essence of the book in your comments. This is a rare gem!

And thank you, good sir, for all your medical detective work. When I saw the images of what this disease does, I got very tearful. Once in a while one sees a child in a wheelchair with these symptoms–now I understand much better.

Thank you so much for this review, Meg! It was wonderful to see that you had pulled out the main threads that run through LeRoy’s journals. He has really touched my soul…

To answer your question about SB putting this book forward to the educational reading market, I am working on a supplementary teaching guide with lesson plans and guiding questions for students. Should you be interested in viewing that once I get it done, I would be thrilled to get your feedback.

Jan Croon

Janet–you may count on me to look at what you have planned. I taught for 33 years–at least half of those years in 5th grade and the rest in middle school, so I know that audience. Huzzah!

Thanks for the fine review. It sounds like a book worth reading, on many levels and for many reasons. You mentioned Anne Frank. When she started her diary at age 13, she was just a year older than LeRoy. In a 1944 entry in her journal, Anne stated: “”When I write, I can shake off all my cares.” Did LeRoy get the same kind of release from writing, do you think? (I’ll answer that question when I read the book, but I’m curious anyway.)

Hi Rob — that’s an excellent question! I think his writing served two purposes. First, he was not enrolled in school due to his disability, and I think his parents understood the inherent benefits that children get through frequent writing. It allowed him to write freely, and as an educator, it was wonderful to see him move through the various levels of understanding as he grew older. And yes, I do think it was a release for him, especially as he grew older and began to more completely understand what he was observing. (No spoilters!)

~Jan

Thanks Janet for answering my question, sort of, without inserting any “spoilters.” Keep up the good work and best of luck with your future projects.

A few of LeRoy’s diary pages are in the book, and his pages look exactly like any middle-school kid would write. He writes his name in a variety of styles, he draws pictures, he really expresses himself. He was a bit upset when he gets to the end of one diary and waited impatiently for the gift of a blank one. He is such a relatable person. I was amazed.

Congratulations, Jan! I know you’ve been working on this for a long time. Congrats to Ted, too. You’ve been talking about putting this out for a while now. I’m emailing Stephanie this afternoon to reserve a signed copy.

You will love this addition to your library, I promise.

I hope you enjoy it, Alex!

How did this diary come to light after more than 150 years? Wonderful review!

That’s a great question! I’d like to know the answer to that too.

Jan, the editor, passed this 2012 article to me last year. I wrote a lengthy Publisher’s Preface about how we obtained it, and the backstory of LeRoy, etc.

Let me know what you think, and please hit the Amazon page, even if you want to order a signed copy from us. It helps a lot.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/invalid-boys-diary-focus-of-library-of-congress-civil-war-exhibit/2012/11/08/c55c7758-21db-11e2-8448-81b1ce7d6978_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6509c4d7a6a5

Thank you, Mr. Savas, for the link. That article answered a lot of my questions. Thank you, also, for publishing this diary as a book. You have thought of everything for a complete book.

Thanks for the kind words, Larry. Please call me Ted. Appreciate your interest and support of our publishing program.

Thank you for this amazing book. I grew up in a town just south of Athens and went to school in Atlanta with a fella named Gretchen from Washington/Wilkes County, and another fellow whose first name was Clisby, who grew up near Macon (Ft Valley,Ga). My own ancestry includes a Presbyterian minister, the first in Ga where he established a church near Athens.

thanks for this insightful work.

You had me until the stupid “White privilege” comment.

A crock of modern, woke, inaccurate B.S Being white didn’t automatically give him privilege. In fact, most whites in the south and in Macon were poor and barely scraped by. Likewise, there were wealthy free blacks (some slave owners) and many other of all colors that were well to do.

Instead of virtue signalling to a modern audience, just say he was “privileged” due to his family’s wealth.