“Grant” by Ron Chernow – A Review

Emerging Civil War welcomes guest author James F. Epperson

Emerging Civil War welcomes guest author James F. Epperson

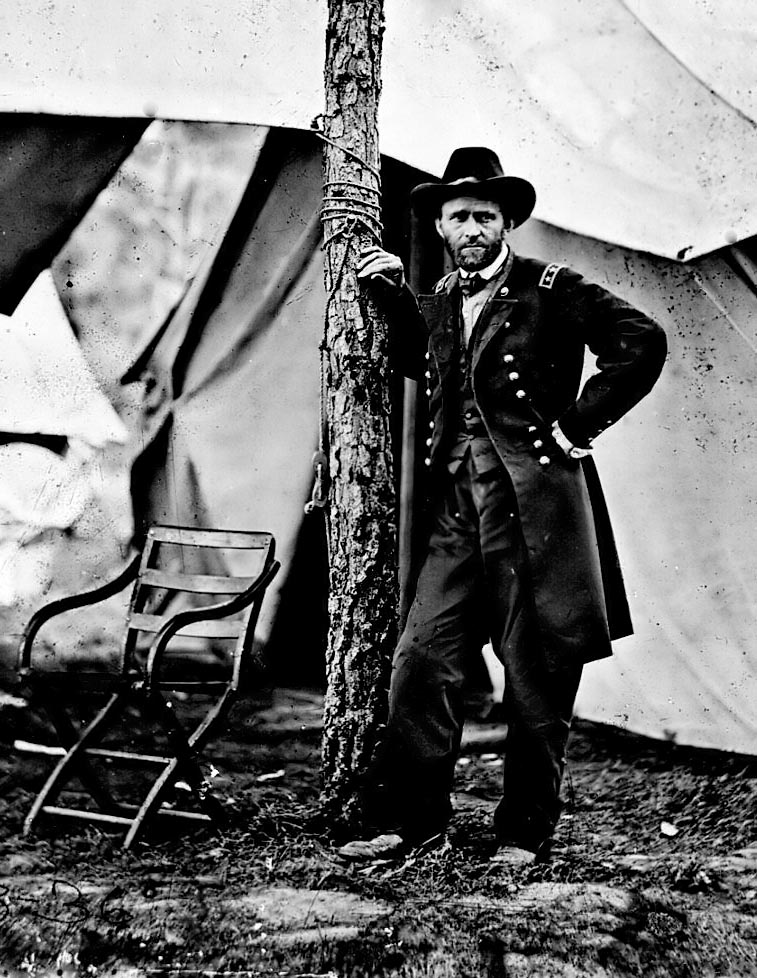

Many compelling tales come out of the history of the American Civil War. One of the most interesting is the story of the slouchy Ohio-born tanner’s son who progressed from leather-goods store clerk to Lieutenant General and commander of the Union armies and who began the war having trouble getting any position at all in the Federal war effort, yet ended up accepting the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in Wilmer McLean’s parlor. There have been many biographies of Grant in recent years, and Chernow’s, while suffering from some flaws, is perhaps the best.

Grant was a complex man, and efforts to reduce him to a simplistic caricature—stolid, taciturn, drunk, butcher, stupid—simply do not stand up to much scrutiny. As Chernow shows, Grant was fundamentally honest, yet was tragically susceptible to being conned by unscrupulous men. Loyal to a fault (literally), he could yet (and did) admit fault regarding men he had tangled with. (He was also quite capable of nursing a grudge.) Whatever his issues with alcohol – and this is a large and important focus of Chernow’s book – he kept them mostly, if imperfectly, in check. He remained absolutely devoted to his wife and just as devoted to the cause of civil rights for the men freed by the war he won. And when faced with an opponent he could not defeat – cancer – he managed a moral and literary victory of epic proportions.

Grant’s life story has been written many times since the 1860s, and the basic outline is generally well-known: First-born child of an Ohio tanner and his pious, near-silent wife; enrolls at West Point in the class of 1843 (graduates 21st out of 39); distinguished service in the Mexican War; difficult period on the west coast leads to his resignation in 1854; struggles to provide for his family in civilian life; re-enters military service as the colonel of an Illinois infantry regiment in 1861; rises to the rank of Lieutenant General, accepting the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House in 1865; is elected to two terms as President of the United States; left destitute by a Wall Street swindler, and confronted by a terminal cancer diagnosis, he writes a magnificent memoir of 336,000 words in less than a year, dying literally days after declaring the job done.

That is the bare-bones version, of course, and there are a lot of details needed to flesh that out. Chernow’s biography ranks near the top of the list of Grant biographies that I’ve read. The first task of a biographer is to understand their subject, warts and all, and I think the author does this.

I have read numerous complaining predictions (on various blogs, mostly) that Chernow’s book is uncritical, but this does not hold up to an actual reading of the text. Chernow’s Grant has an alcohol problem, can be over-confident as a military commander, was clearly not expecting the Confederate attack at Shiloh, does not perceive the ethical issues in accepting gifts from wealthy benefactors, and is consistently unable to avoid being “conned” by public or private associates. If that is not being critical, then I guess I don’t know what the word means.

There are three specific issues I’d like to address in some detail.

While Chernow’s treatment of Grant’s Civil War campaigns is far superior to that in Ronald White’s American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant, the absence of any campaign studies from the bibliography troubled me. Considering Chernow was not coming to this project as a “Civil War historian,” I think it is reasonable to expect him to spend some time with the many fine works that exist on Shiloh, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, the 1864 campaign in Virginia, etc. He does list a number of “standard” histories of the Civil War, including outstanding works by Catton, Foote, and McPherson.

One cannot review this book without some discussion of Chernow’s treatment of Grant’s drinking. My personal view concludes it is both a strength and a weakness of the book. Chernow offers more detail on the subject than most Grant biographers, much of it drawn from the Hamlin Garland Papers, copies of which have apparently been archived at the Grant Library at Mississippi State University (Garland wrote perhaps the first scholarly biography of Grant in 1898 and conducted many interviews with people who had known him). While Chernow occasionally presents fresh perspectives on well-known incidents, he usually provides very little evaluation of the evidence. Essentially – and this is a bit of an over-simplification, but I think it is essentially correct – he presents nearly every story, anecdote, or rumor that he can find, putting them all on equal footing. His basic thesis presents Grant as a binge-drinker, someone who, once started, could not help going downhill into full intoxication. In this regard, Chernow follows James McPherson, who put forward essentially the same thesis in his highly regarded Battle Cry of Freedom (page 589), drawing heavily on an article by Lyle Dorsett (“The Problem of Grant’s Drinking During the Civil War,” Hayes Historical Journal vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 37–48, 1983). Neither Chernow nor McPherson spend much time assessing the evidence that exists, and while McPherson – who was writing a single-volume survey of the entire Civil War – can perhaps be forgiven, Chernow should have done more critical analysis. In particular, Chernow should have paid more attention to the many dogs that did not bark.

There are several anecdotes showing Grant was able, on occasion, to take a drink without going on a “binge.” There are also indications that those close to Grant knew they could offer him a drink without risking anything. For example, there is an oft-cited story in which Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson, one of Grant’s corps commanders during the Vicksburg campaign, suggests Grant should take a break from studying how to crack the Confederate citadel, “join with us in a few toasts, and throw this burden off your mind” (page 253). There are several other, similar stories, including bottles of alcohol being sent to Grant by his own family. My point is not that Chernow has misrepresented anything. My point is that the full story is more complex than Chernow presents. Did Grant drink? Certainly. Did he sometimes drink too much? Almost surely. But between the uncontrollable binge-drinker and ordinary social drinker, there lies a wide range of alternative realities in which I think the truth lies, and the author should have mined this vein.

Some of the best parts of the book are the several chapters devoted to Grant’s political career, including his two terms as President (and his effort at a third term in 1880). The traditional view of Grant as a politician generally ranges from corrupt to inept, and there certainly is much to criticize here – which Chernow does. But he also points out that Grant’s over-riding motivation for getting in to politics was to secure what had been purchased with blood during the war: the freedom of the former slaves, not only theoretically, but as a practical matter. Frederick Douglas, an appropriate authority on this, said, “That sturdy old Roman, Benjamin Butler, made the negro a contraband, Abraham Lincoln made him a freeman, and Gen. Ulysses S. Grant made him a citizen” (page 858). Grant’s embrace of the ethically-challenged Stalwart wing of the Republican Party was driven by the very valid fear that the more reform-minded wing of the party was willing to sell out the Republicans in the South, who were mostly freed slaves. The entire reason for toying with a third term in 1880 was the fear of what a Democratic victory might mean for the freedmen.

This biography, although very well-written, is not for a casual reader – at 1,200 pages, it is not a weekend read – but it rewards those who reach the final page, when William T. Sherman and Mark Twain sit down with cigars and whiskey to talk about their friend, after his funeral.

James F. Epperson is a 60-something child of the 60s (both 19th and 20th Centuries) who taught university mathematics for 21 years before moving to Ann Arbor, MI to take a position in academic publishing. He is a frequent speaker at CWRTs, maintains a number of Civil War-related websites and lives modestly in Ann Arbor with his wife of 35 years and their elderly Border Collie. Check-out his websites http://www.civilwarcauses.org/ http://www.petersburgsiege.org/, and http://www.jfepperson.org/chrono.htm

James

Im listening to the book on audible. It is a great “listen.” Ive finished listening to the Civil War portion of the book. The book now heads into his becoming a candidate for President. The book does go “far” into his drinking. It was far more serious than Id thought. The book tells me, as I interpret the book, that Grant and Lee did not appreciate “alot” or much like each other. They are a study of old and new generations. Its amazing how Grant rose to power so quickly and so far in social status. Its a complicated “read.” Ive grown to not like or appreciate the Confederacy or hardly anyone in the Confederacy, including Lee. Ron Chernow’s Grant is an attempt to damage the “Lost Cause” mentality and place the Northern cause “in the right” as the Confederacy is “in the wrong.” I wish the re enacting of the Civil War would end and we can bury this war. It was a cold-blooded mass murder and the flags need to be put away in museums and cemetaries where they belong. The Confederate battle flags and statues are an insult to the lives lost to end it. We need to “emerge” into a a better world and not wallow in the past.

Thanks very much for this review, Mr. Epperson. I have read any number of Grant biographies, and without question this complicated man is finally get his “just desserts”. Chernow does bring out his flaws very well, and I was happy to see Grant’s alcoholism being discussed in a modern way. In fact, his mastery over his disease when it counted most makes me admire him even more. Your comments were very well made and they helped me come to my own opinion of reading this excellent biography. Thanks again.

IMO, Chernow’s bio scores very high on the “completeness” metric (it isn’t just a military biography), high on the literary metric (the writing is good, but not as good as Catton), and is a “strong OK” (but only that) on the military history. Since he was writing a biography of “the whole man,” I am willing to overlook the weaknesses in the campaign descriptions.

Who is the narrator of the audio-book? I’ve never been able to get into that format, but I appreciate that others love it.

(PS: Y’all call me “Jim,” OK?)

James:

I read Chernow’s bio about four months ago. I agree with you about Chernow’s obsession with Grant’s drinking. He repeats every tale with almost no analysis of what’s probably true and what’s tripe. Jealousies and gossip were rife among Army officers, so skepticism should be any historian’s byword when dealing with Grant’s drinking. Also, some perspective would have been helpful. Everyone, except maybe John Rawlins, drank in those days. Heck, sipping booze was probably healthier than sipping water back then.

I thought Chernow’s perspective on Grant’s parents was interesting. Not enough has been written about Grant’s upbringing in Georgetown, Ohio, and his time at West Point.

Overall, I was a bit disappointed. Not much new stuff. I expected more from Chernow. Maybe it’s just that I’ve read too many other books on Grant.

Jim,

I am just finishing Chernow’s biography of Grant and generally agree with your well written review. However, I cannot agree with your analysis of Chernow’s treatment of Grant’s alcoholism. First of all I do not think that Chernow ” presents nearly every story, anecdote, or rumor that he can find, putting them all on equal footing.” He examines the accounts of Grant’s drunkenness and points out the probable biases of the source of the gossip. He goes one step further and examines the context of the recounting ti evaluate the credibility of the story. Chernow’s biography of Hamilton also looks at accounts of his life that are suspect (including one involving the identity of his father) and opines as to their credibility. I think that a biography of a subject needs to also examine myths that have grown up around the subject and give the reader enough information to determine whether they should be considered facts.

The second problem I have with your review is your observation ” between the uncontrollable binge-drinker and ordinary social drinker, there lies a wide range of alternative realities in which I think the truth lies, and the author should have mined this vein.” I don’t know from where you garnered this opinion of the various levels of alcoholism, but I doubt if you will find anyone who has undertaken a serious study of that disease who would agree with you. An alcoholic has two realities: drinking or not drinking. An alcoholic is always an alcoholic, and can never be a social drinker. I had to stop drinking 26 years ago when I saw problems developing toward an addiction, and others that I have come to know cannot take a drink without sliding down the slope to try to climb the steep slope back to abstinence. I urge you to attend an AA meeting as an observer to discover what an alcoholic is rather than assume a “middle ground” which simply does not exist.

The two “drinking stories” that made me write about “putting them all on equal footing” were:

1. The rumor that someone had seen someone who they thought might be Grant staggering around Washington the night before the 1868 election;

and

2. The totally over-the-top story of Grant getting drunk at a dinner in India and making advances on various female guests.

I thought the first tale was little more than rumor, and the second one was so out of character that it did not warrant mention, *except* perhaps as an example of how stories about Grant’s drinking emerged out of almost thin air.

(Caveat: I’m on the road and don’t have my copy of the book to check things.)

On your second point, I fear I did not make myself clear. It is not clear to me that Grant was an alcoholic—he may just have been someone who occasionally drank more than he should. Now, if that means that, in your eyes, Grant *is* an alcoholic, then we simply are working with different definitions.

Chernow’s book is based on the assumption that Grant was an alcoholic, and appears to have all the symptoms of the disease. There are first hand accounts of Grant’s binges that didn’t even make them into Chernow’s book such as the binge during the siege at Vicksburg when Rawlins returned home on leave, and General “Baldy” Smith’s letter to his Senator Justin Morrill describing another binge during the Petersburg campaign that, in addition to his failure to break the Dimmock Line before the rest of Grant’s army got into position after crossing the James ended his active military career. I believe the evidence presented by Chernow and my own research make it quite clear to me and the majority of others who studied Grant that he was an alcoholic

(OK, I’m back.)

I think Chernow’s “assumption” is the crux of my problem. Of course, analyzing/diagnosing something like this for an historical figure is tough. Chernow does cover the “Yazoo bender” (p. 272 +/-) as well as Smith’s allegations (p. 422).

My take on the book is much more negative. I will say Chernow’s Grant is better than the more recent hagiography. It is because Chernow is willing to go into Grant’s flaws, in particular the alcoholism.

That said, my issue is that while Chernow points out the flaws, he does not see them as crippling. It works with the alcoholism angle; Grant does overcome his problem with drink to become a successful military commander. I take more issue with his interpretation of his presidency in this regard. Ultimately, in Chernow Grant is a good president doing what he does for noble ends. It is an argument I do not agree with, either in terms of his motives or his competence as a president.

The view of Grant as a civil rights hero is a product of propaganda then and the recent triumphant of the Just Cause interpretation. It has its share of holes. Grant had a better civil rights record than the men who followed him, but his policies had major limitations, and those limitations go a long way to explaining the failure of Reconstruction. The current narrative, which can be summed up as “the war did not end at Appomattox” fails to understand why the North’s support for Reconstruction was fractured. There is a difference between those who wanted equal rights and those who wanted to punish the South and make the Republican Party unstoppable. Nor does it consider the rise of the conservative business class, which Grant was allied to nor the fact that the North’s main uniting motive in fighting was preservation of the union. It is why someone such as Frank Blair, a hardcore racist, was himself a very successful and committed Union general. I do not mean these points are ignored, but rather that they are not the current vogue in studies on the period.

As you noted, the military portion of the book is a bit thin in terms of research. Like McFeely, I get the feeling he wanted to get to the politics bit.

Your review was well written and thoughtful, which is rare in all the recent gushingly over this book. As much as it is heresy for the Grant crowd, I still prefer McFeely. Among the pro-Grant books, Simpson is still the best all around.

Thanks for the comments, Sean. I remember reading McFeely long ago, and shaking my head quite often at things he said. I thought Brooks Simpson did a good job of torpedoing much of McFeely’s outlook in his 1987 article in Civil War History.

Forgive the terse response—after ten hours in a very cramped car, I need to turn in.

(Sometimes the limited threading on blog discussions defeats me. This is in response to Mr. Martin’s concern’s, above.)

“Baldy” Smith’s various allegations are a good point to raise in terms of “assessing the evidence.” In addition to his letter to his Senator, Smith wrote a “private memoir” for his daughter, which was not published until the 1980s. In this he mounts a defense of his actions at Petersburg on June 15, and he also tells some more tales about Grant and alcohol. Now, is this good information? It’s a memoir, written long after the events, by a man clearly with an axe to grind. Is he being truthful? Or is he indulging in some “historical revenge”? Obviously, we can’t know for certain, and verification either way would be very difficult. Chernow did not discuss these allegations (I don’t think this memoir of Smith’s is in his bibliography), but this kind of assessment of the evidence is what, IMO, is missing.

Jim: To add to the mix, I’d point out that Smith apparently relied in part on a report to him from Franklin regarding Grant’s drinking. That pair already had a track record of meddling with a commanding officer through political intrigue. Moreover, Smith was no stranger to possibly false allegations of drinking, having himself has been the subject of allegations that he was drunk during the fighting at Dam No. 1 in April, 1862 (if I recall correctly). There is little doubt that there were incidents when Grant had too much to drink during the Civil war. Whether he was an “alcoholic” under various definitions and whether that interfered with his exercise of command are legitimate points of discussion. But that’s different from crediting every story regardless of source, etc.

Jim, a well written review.

Hi Jim! Just saw on the AACWRT website that you had posted a review here. I recently read H.W. Brands book The Man Who Saved the Union Ulysses Grant in War and Peace. Have you read this? It sounds a lot like Chernow’s book in some ways – light on the military stuff, etc. It was more than 600 pages long, so I’m suffering from a bit of “Grant fatigue” and I was wondering if you thought it was worth the effort to read Chernow’s book. I have read Chernow’s bios of Hamilton, Washington, and Rockefeller and generally like his style (although having read Hamilton I confess that I would never have thought that this book would inspire a hit musical.)

Chernow”s “Grant” gives the first real examination of his alcoholism. Mr. Epperson and I disagree on Grant’s ability to control his addiction, but as an attorney and dealing with alcoholic clients, I feel my opinion comes from first hand observation. I have yet to hear from Mr. Epperson on his basis for his opinion Chernow presents. “Did Grant drink? Certainly. Did he sometimes drink too much? Almost surely. But between the uncontrollable binge-drinker and ordinary social drinker, there lies a wide range of alternative realities in which I think the truth lies, and the author should have mined this vein.” Binge drinking is also the result of alcoholism. Me thinks that Mr. Epperson may be mired in a river in Egypt, “denial.;”

No, I have not read Brands.

The basis for my opinion is my own experience, the details of which I prefer not to make public. You say that “Binge drinking is also the result of alcoholism.” That is true. But not everyone who indulges in a “drinking binge” is an alcoholic—otherwise, a large fraction of the collegiate population would have to be considered alcoholics.

I enjoyed your review, and enjoyed the book too. I’d read a few others on Grant beforehand, beginning with Ronald White’s. Thanks for your analysis of the sources for Chernow’s accounts of Grant’s drinking. I think it’s fair to be critical of the research done for the “definitive” biography of this complex man. The drinking had to be addressed, since it’s all that most people “know” about Grant, but I wish Chernow had done better research in that area and been less fond of proving his own theories.

All do repect, I think your review is somewhat self-serving, it is more about what you wanted to read versus what Chernow was writing about. Ron Chernow is not a military historian, he is a biographer. I dont think Chernow ever intended to think that his biography would describe battlefiled tactics and where every cannon ball fell. In this regard, I think that Chernow met and exceeded what he intended to accomplish, a very well written, researched biography of US Grant, the person.