An Unknown Soldier At Port Hudson

Emerging Civil War welcomes guest author Dan Wambaugh

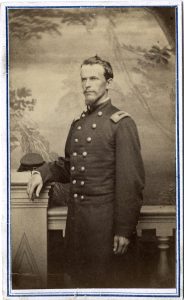

Major Edward Bacon was under arrest. Formerly commander of the 6th Michigan infantry, he had openly criticized his division commander Brigadier General William Dwight too many times during the course of the siege of Port Hudson, and so he would spend the final weeks of the campaign at a plantation house a half mile in the rear of division headquarters. Bacon, in his memoir “Among the Cotton Thieves,” is openly critical of criminal acts in the Department of the Gulf, and is disgusted by the incompetence of his immediate commanders.**

Bacon’s situation at Port Hudson did afford one unique opportunity, however. Unburdened by duties, he was free on July 10th, 1863 to slip away from his place of arrest and examine the defenses at Port Hudson while the surrender proceedings were underway. What he wrote is a detailed description of varying points along the line. Bacon starts: “The troops are gone, federals and rebels. All is silent except the voices of insects and creeping things, singing to the blazing noon.”[1] He marvels at the simplicity of the earthworks, saying “And this is Port Hudson? The ditch is about four feet deep in most places, but in many places the clay has crumbled down so as to lessen that depth to one or two feet. The parapet is about four feet high, and about the same number of feet in thickness. The revetment is of common fence rails, held in place by stakes. I see where several light artillery shots have gone through both parapet and rails.”[2]

As he travels among the emplacements, he notes several interesting observations, including coming across a brass twelve-pound howitzer that was salvaged from the tin clad Barataria, which members of the 6th Michigan had been on board when it sank in a Louisiana lake the year before. He goes into great detail describing the artillery pieces, and the ingenious ways that some guns are hidden in places that are immune to federal shells, but may be swung into position at a moment’s notice to repel attackers. Even the artillery ammunition does not escape his keen eye:

“The ammunition is in ammunition chests or caissons, sometimes hid in little magazines, and sometimes put close to thick parts of the parapet. The powder of the cartridges is not held by flannel of a uniform color, such as I have been used to seeing, but is held by all kinds of woolen and calico, of every print and color. Much of this cloth is worn, and has evidently been cut from articles of female wearing apparel. Here is the delaine, the merino, the linsey-woolsey, and beside the homespun flannel is seen stuff cut from costly shawls, all contributed by Southern women. I see, also that the sand bags on the parapet are mostly made of sheets and table-cloths, often of the best linen. Many fine pillow-cases, marked with their owners’ names, lie filled with sand, needing no change to adapt them to their new use.”[3]

Entering the town, Bacon mingles among Confederate POWs, recently disarmed and being guarded by African-American soldiers. “The officers and soldiers are clothed almost alike, and seem to have lived on equality. There is a sort of vivacity and spirit in these men which no surrender can kill.”

Bacon hastened through town, and there comes across a singularly unique scene:

“In passing through a wooded hollow, I find two men digging a grave. One is a well known soldier of my own regiment, and the other is a stout, cotton-clad rebel, wearing an old slouched hat. A piece of tent cloth near by appears to be spread over two dead bodies. The Michigan man drops his pick in astonishment on seeing me. I inquire of him who is to be buried. He answers ‘One of our Company F boys, who was wounded and taken prisoner in the whisky charge,’ and with that he turns down the tent cloth, and tries to keep the flies away. There is the face of a brave boy, well known to me through weary years of war and suffering. His pallid, emaciated face is marked with agony, and his breast, under his blue coat is strangely sunken.

‘When did he die?’ I ask.

‘To-day,’ is the answer, and the soldier beside me continues, ‘He was shot in the shoulder. He lived till we got in after the surrender. He said the confederates did as well for him as for their own men, but they had no medicine or anything else he needed. There were not men enough to attend to the wounded. The flies got to his wound, and his shoulder was full of worms. He seemed very glad to see us. He said he hoped that his death would be for the good of his country in some way.’

The sharp-eyed rebel who stands by says, ‘Excuse me, sir, but I hope you will not think we neglected wounded prisoners,’ and as he points to the corpse of his countryman that lies buttoned in gray uniform before us, he proceeds, ‘This man, too, was wounded, but such was our want of everything, and especially of attendants, that he died in the same manner that your man died. They lay near each other in the hospital tent, and were very friendly to each other, so we thought they would not be displeased if they knew their bodies were to rest side by side in one grave.’

As I leave I hear the two picks at work breaking the hard, dry clay, deepening and widening the grave.”[4]

Benjamin Johnson, of Company F 6th Michigan described the “Whisky Charge” of June 29th in his book A soldier’s life, the Civil War experiences of Ben C. Johnson.

“Gen. Dwight…issued an order for the Sixth to charge from their rifle pits into the citadel of the enemy, and having possessed it to hold it against the Confederates…Our men were always ready to obey commands and quite a squad of them rushed out into the Rebel works. In the meantime our valiant General became stupidly unconscious from the effects of ‘commissary’ (whisky) administered to keep up his courage while he lay closely hugging the most secure part of our works.”[5]

Major Bacon was even more critical of the night attack that became known as the “Whisky Charge”, and especially critical of the man who ordered it. “[Dwight] waited long, drank often, and was heard making great promises of promotion to the staff officers who bore him away from the field of his fame. He seemed to think that the citadel was taken and reduced to his possession, and that was all done by himself.”[6] In reality, the men of the 6th Michigan and the 165th New York stayed pinned down in a forward position through the night and into the next day, withdrawing in ones and twos until the entire attacking force was back in their jumping off position.

Ben Johnson wrote:

“Wounded and bleeding our men were driven out by the overwhelming odds dashed against them. Several were made prisoners, while others made good their escape back into our own works. One of my esteemed comrades was severely wounded and made prisoner. After the surrender of the garrison we visited their hospital and found our comrade in a dying condition. His wounds had not received proper care, gangrene had set in, and the poor boy was just able to send a dying message to his loved friends, and the brave spirit fled to the home beyond the river.”[7]

Here Private Johnson is clearly referring to the same Michigan soldier that Major Bacon saw being buried. While both authors coincidentally encountered this soldier, both neglected to name him. Perhaps in deference to the privacy of his family, or maybe some discretion at a possible stigma the soldier could bear being buried with a rebel had him consider withholding the name of the soldier that was “well-known” to him.

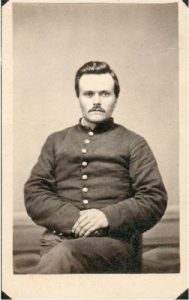

So who was this soldier, wounded in the “Whisky Charge”, captured, held in a Confederate hospital, befriended by a similarly wounded rebel soldier, and buried in a grave alongside that soldier in the Louisiana clay far from his Michigan home? Both authors knew the man, and identify him as belonging to Company F of the 6th Michigan Infantry. Consequently, only one soldier from Company F is listed as having been wounded on 6/30/1863 and dying on 7/10/1863, the day after the garrison surrendered: Private Delos Markham.

Twenty-year-old Private Delos Markham enlisted in company F of the 6th Michigan Infantry on August 10th, 1861. A week later on August 17th his older brother Orrin enlisted in Company F, leaving their widowed mother Sarah to raise their sixteen-year old brother and thirteen-year-old sister on her modest Washtenaw County farm. Orrin would be one of the 432 men of the 6th Michigan who would die of disease, passing away in Baton Rouge on July 18th, 1862. Delos would be wounded and die almost exactly a year later, being buried in Port Hudson. In all, Sarah Markham would have four sons enlist in the Federal army, with her other son Galen being discharged for disability from the 4th Michigan Cavalry, and her youngest son Albert deserting from the 27th Michigan five months after enlisting.

Today, Delos Markham’s gravesite is unknown. He is listed in no database or national registry, and he has no marked grave at Port Hudson National Cemetery. His mother lies today in a small cemetery near their home in Augusta Township, Michigan, but Delos is not there. It is most likely that he lies today in the same spot where he was buried that hot day in July 1863, in a wooded hollow outside Port Hudson. There his remains can be found still, in an anonymous grave in the Louisiana woods, lying alongside the remains of another unknown soldier who should have been his enemy, but was instead his friend at the end.

**Written immediately after the war and published in 1867, Edward Bacon’s book can easily be considered the Civil War equivalent of a modern day “tell-all.” Nevertheless, with the memories still fresh and the emotions of his frustrating time in the service still at the forefront of his writing, Bacon’s account is a refreshing “Technicolor” alternative to the often sepia-toned romanticized memoirs written by middle-aged and elderly veterans decades later.

————

Dan Wambaugh holds degrees from Michigan State and Oxford Universities. Since 2000 he has owned and operated his own business, reproducing handmade Civil War era military uniforms. He lives in Charlotte, Michigan.

[1] Bacon, Edward, Among the Cotton Thieves, (Detroit, MI: The Free Press Steam Book and Job Printing House, 1867), 283

[2] Bacon, Cotton Thieves…, 283-284

[3] Bacon, Cotton Thieves…, 286

[4] Bacon, Cotton Thieves…, 290-291

[5] Johnson, Ben C., A Soldier’s Life: The Civil War Experiences of Ben C. Johnson, (Kalamazoo, MI: Western Michigan University Press. 1962), 92

[6] Bacon, Cotton Thieves…, 262

[7] Johnson, Soldier’s Life…, 92

Superb article. Thank you.

Thank you Dan Wambaugh. Appropriately enough, I’m reading this for the first time on Memorial Day. I love the fact that it is about a Union soldier and Confederate soldier, men who fought each other as enemies, were wounded and, apparently, died on friendly terms. Rest in peace. Nice detective work to dig up Delos Markham’s family story, which added to the poignancy of an already moving story.

Dan Wambaugh – thanks so much for your thoughtful examination of Edward Bacon’s book – could you let me know where you located his photo? I am writing a book about his granddaughter (my great aunt) and I would like to include it, as they had a close relationship, and he helped to facilitate her 50 year career as a professional musician.

Several years ago a grave outside the former town of Port Hudson was found to have two unidentified soldiers, one Union, One Confederate buried together in the same grave. The remains were removed to the front of the battlefield State Park nearby and given a new burial with headstone as the grave of the unknown soldiers of Port Hudson. I wonder if these are the same two soldiers. I have not visited the park in a while, maybe someone has figured it out since then.